John ALSTON of Stisted & Belchamp Otten [3116]

- Baptised: 23 Dec 1576, Newton Nr Sudbury SFK

- Marriage (1): Anne CROCHERODE [3117] about 1588

- Died: Manor Of Kentish Stisted ESS

- Buried: 13 Sep 1656, All Saints Stisted

General Notes: General Notes:

John settled at the Manor of Kentish, Stisted with lands at Boxford and Hadleigh.

Image of Kentish Manor House shows the late Tom Perrett, genealogist.

In the Visitations of Essex1 1664-1668 it mentions ,

ALSTON of Stisted

William of Newton = Elizabeth Hampstead

John of Stisted = Anne Crachrood

2. Matthew, 3. William. LeStrange, Gent, 1665 = Hannah

1. A Visitation is a regular and formal visit by an Archbishop, Bishop, Archdeacon or Rural Dean to the parishes under his control, or to a convenient central meeting place, usually in conjunction with a fact-finding exercise.

The Manor of Husses Toppesfield: William Cratchrode Jnr held this Manor in 1585, about the latter end of Queen Elizabeth it was holden by John Alston of Belchamp-Oton, who gave it to his third son . . . . . Matthew, and he having no issue bequeathed it to . . . . . Thomas Cracherode.

Ref: History of the County of Essex. Rev P Morant Vol II ERO (See more below)

Extract from his father William's Will:

To my son John Allston, and his heirs, all household and farm implements, crops and cattle on Bloyes Farm, Sible Hedingham, Essex. Also Awbins Farm in Boxford in the fee of Hadleigh, Suffolk. Also the property bought of Richard Sendall and Stephen Cooke now in the occupation of John Coppin in Boxford, Suffolk. Also L2133.6s.8d to be paid in three equal portions at 4, 12 and 18 months after my decease. He is let off his debts to me.

Kentishes Stisted was alienated 5 July 1631 to John Alston of Hawkishall in Topesfield who bequeathed it to his son L'Estrange Alston who bequeathed it 20 April 1678 to John Alston his nephew and after him to another nephew named L'Estrange this last bequeathed it 22 April 1689 to his sister Elizabeth wife of William Jegon and to her heirs for ever.

Alstoniana Pg 358

PARKER v. ALSTON.

Bill, 4 February 1623, by John Parker of Toppesfield, co. Essex, yeoman, v. John Alston of Toppesfield, gent. Re a mortgage made to defendant by complainant.

The only personal particulars to be gleaned from both bill and answer is that one William Alston of Newton in Suffolk, defendant's brother, was one of the two arbitrators elected by the parties ; and that defendant was indebted to Lestrange Alston in the sum of L130 for his legacy given unto him by William Alston, deed., his grandfather, and lately paid to this defendant by the said William's executors.

Mitford . 28/101. 1623/4.

Alstoniana Pg 196

GREENE v. ALSTONE.

Bill, 26 January 1627/8, by William Greene of Toppesfield, co. Essex, yeoman, v. John Alston of Toppesfield, gent.

The suit relates solely to disputed payment of money due under a bond to defendant, his wife, Anne Alston, received into her own hands at his house at Toppesfield L20 of the amount due.

Mitford. 87/24. 1627/28.

Alstoniana Pg 197

GREEN v. ALSTON.

Answer, 7 February 1627/8, of John Alstone, one of the defendants to the bill of complaint of William Green (above).

This is the answer to the complaint of William Green and relates solely to the payment of sums in question, with no personal particulars whatever.

Whittington 425 1627/28.

Alstoniana Pg 197

GREEN v. ALSTONE.

William Greene v. John Alstone, gent.

Depositions taken at Toppesfeild, co, Essex, 13 January 4 Ch. I. (1629). Re disputed bond above.

No Alston depondents

Mitford. 639. 1629

Essex Record Office T/A 418/107/73

CALENDAR OF ESSEX ASSIZE RECORDS

Calendar of Essex Assize File [ASS 35/72/2] Assizes held at Chelmsford 7 July 1630

Dates of Creation 10 March 1630

Scope and Content Writ of Distringas ( to distrain ) for Henry Mildmay of Moulsham knt., Gamaliel Capell knt. and William Luckine bart., both of little Waltham, Thomas Titterell of Abberton, Thomas Pinson of Rayleigh, Robert Gouldinge of Great Henny, John Alston of Toppesfield gentlemen, to answer for transgressions "for (not mending) Peete bridge and Blackwater bridge". Issues of each, 10s. (ASS 35/72/2/73)

T/A 418/106/68

Writ of Distringas for Robert Golding of Great Henney, John Alston of Toppesfield and James Harrington of Great Maplestead gents., to answer for trespasses.

Blackwater Bridge et. al. Proclamation Lent 4 Chas.I. 3s.4d. each'. [ASS 35/72/1/68] 1629

Essex Record Office T/A 418/108/143

CALENDAR OF ESSEX ASSIZE RECORDS

Calendar of Essex Assize File [ASS 35/73/1] Assizes held at Brentwood 17 March 1631

Dates of Creation 7 July 1630

Scope and Content Writ of distringas for Henry Mildmay of Moulsham knt., Gmaliel Capell knt., William Luckins of Little Waltham, Thomas Titterell of Abberton, Thomas Pinson of Rayleigh, Robert Gouldinge of Great Henny, John Alston of Tollesfield, all gents., to answer for transgressions etc. Proclamation made Lnet 2 & 4 Chas.I. Issue, 5s. (ASS 35/73/1/143) 1630

Essex Record Office T/A 418/109/78

CALENDAR OF ESSEX ASSIZE RECORDS

Calendar of Essex Assize File [ASS 35/74/1] Assizes held at Chelmsford 7 March 1632

Dates of Creation 25 July 1631

Scope and Content Writ of Distringas for Henry Mildmay of Moulsham, Gamaliel Capell knts., William Luckinge bart., Thomas Titterell of Abberton, Thomas Pinson of Rayleigh, Robert Gouldinge of Great Henny, John Alston of Toppesfield, all gents., to answer for transgressions etc. Proclamation made Lent 2 & 4 Chas.I. Issues for each, 13s.4d. (ASS 35/74/1/78) 1631

ALSTON v. AYLETT.

Chancery Proceedings. Charles I. A. 36.

Bill 31 January 1634/35 by John Alston of Toppisfeild, co. Essex, gent. V. Robert Aylett.

One John Bolthode late of Stystead, co. Essex, deceased, was seised of a loft called Powlyes, and divers lands and tenements in Stystead, which on his death descended to his three daughters and coheirs, viz. Joane, married to Robert Harrys of Danbury, Phillipp married to John Hatch, and Joane married and to Robert Sawen, both of Stystead.

Defendant has purchased the part of Robert Sawen and his wife, Plaintiff that of John Hatch and his wife; and, there being but one deed thereof, which has come into defendant's hands, the plaintiff cannot defend his right to his third. Defendant says Alston has denied him due way and passage to and through the property, and the deed being ancient and the place names having been mostly changed, he could prove but few, and he desired a commission to examine into the matter &c, &c.

Note: PRO C 5/23/1 Alston v. Aylett: Essex 1654 may refer but not searched 2007

ALSTON v. AYLETT. 1654.

Chancery Proceedings before 1714. Bridges. 23.

Bill, 12 June 1654, by John Alston of Stysted, Essex, gent., v. Robert Aylett.

Another bill in the same matter as Alston v. Aylett, (Charles I. A. 36. q.v. above.)

Alstoniana see Table 23 Page 21, and same suit ubi supra

Essex Record Office Q/SR 317/40

SESSIONS ROLLS MIDSUMMER

Dates of Creation 12 April 1642.

Scope and Content Presentment Mr. John Alston was chosen surveyor, and the constables and churchwardens have not appointed the 6 days for the amendment of the highways which ought to be appointed the Sunday after Easter. Signature of: John Alston. Added in a different hand:This presentment was tendered to me by the surveyor of Stisted the day abovesaid. Signature of : James Heron. 1642

(It is assumed this is John Alston of Stisted)

Essex Record Office Q/SR 324/118,119

COURT IN SESSION: SESSIONS ROLL EASTER 1645

Dates of Creation 28,29 March 1645.

Scope and Content: EXAMINATIONS taken at Halstead before Thomas Cooke esq., justice, of "divers parties about the business of Mr. John Alston of Stistead." (The depositions are confused in their subject matter, and of no historical interest except for the passages calendared below; there is nothing else in the original to throw further light on the conjuror.) Martin Hurrell deposes that, between Easter and Michaelmas 1643 being the last summer but one, Mr. Robert Aylett, Mr. Thomas Allett and Mr. James Richardson, Sarah Feltcher, Abraham aham Rich, John Drake, John Dier, all of Stisted, Lambert Smith and "the conjuror that went in black apparell, of a browne haire and a blackish heard", a man of middle size, and another one Henry, the three last came from Sir William Maxie, and two maids of the same family, and sometimes William Drake and his wife of Stisted, Ellen Warren, Mary Wardthen of Bocking, now married to Stistead, and Mr. Edward Mott of Bocking, and divers others, had half a dozen meetings at her master's house (etc.). And further she saith that Sir William Maxie's man did conjure by making a circle in her master's hall, and setting up three candles which burned blue and when they put them out they did it with milk and soot; and saith that they feasted and had fiddlers from Coggeshall and Sir William Maxsie's maid played on the virginals; that she took a bushel of wheat (out) of the malt chamber and gave it to Robert Wibrook for which she was to have 3s., and Elizabeth Waite stole 2 bushels of malt and sent to young Samuel's to be brewed for a merry meeting, and finally saith that they rode in a coach to Sir William Maxie's.

Essex Record Office Q/SR 335/26

COURT IN SESSION: SESSIONS ROLL EPIPHANY 1648

Dates of Creation 11 January 1648

Scope and Content Presentments by Hundreds of Hinckford and Witham. The inhabintants of Wethersfield, for not repairing the highway from Toppesfield towards Braintree being against the lands of John Alston gentleman commoly called "Hawkesells" as for as "Cellyers greene" by estimation 100 rods. The inhabitants of Alphamstone, for not repairing the highway from Lammarsh to Febmarsh and Halstead, the place is called "Wellockes hill" Mrs Clarke of Stebbing widow and William Field yeoman, both of Steebbing, for recusants. John Roylands of Stebbing weaver, for sparating himself from the parish church of Stebbing and frequenting other unlawful meetings whre he himself preseheth to others. Peter Lidgecatt and John Sanders, Richard Casse and John Wilmott, all of Hatfield Several yeoman, for recusants. (blank) Sanders of Ratfield Peverel, for an unlicenced alehousekeeper. Mark

of: Robert Warner Foreman of the jury: the rest of the jur consent. 1648

Essex Record Office Q/SO 1/220

ORDER BOOK EPIPHANY 1652 - MICHAELMAS 1661

1654

Extract - . . . . . And whereas John Alston gent[leman], father of the said Henry, being convicted for swearing severall oathes, Dionisius Wakering Esq[uire], one of the Justices of the peace of this County, before whom the said Convicc[i]on was, directed his warrant to the Constables, Churchwardens and overseors of the poore of the said parish for the levying the Twenty Shillings of the goods of the said John Alston for his said offence, . . . . .

See Henry Alston [3139]

30 Mar 1654 John Alston holds land called Prke? (Priests) Grove pasture and Little Wrights, (also Bakers Undated)

Ref. Manor of Prayors alias Bourne Hall ESS.

Alston v Aylett

Chancery Proceedings before 1714. Bridges. 23.

Bill 12 June 1654, by John Alston of Stysted, Essex, gent., v. Robert Aylett.

Another bill in the same matter as Alston v. Aylett, above.

Alstoniana Pg 173 & 175.

Essex Record Office T/A 418/144/23

CALENDAR OF ESSEX ASSIZE RECORDS

Assizes held at Chelmsford 19 July 1654

Dates of Creation 20 April 1654

Scope and Content Indictment of Rob.Aylett, Robert Wood, John Wood, William Lambard, Thomas Harris, George Hurrell, all of Stisted yeoman, John Smith of Bocking, John Wodle and Isaac Medroppe of Stisted yeoman riotously assembled at Stisted and broke a wooden gate worth 8s.6d. belonging to John Alston. Witnesses: John, Lestrange, Anne Alston. [ASS 35/95/2/23]

Essex Record Office T/A 418/144/22

CALENDAR OF ESSEX ASSIZE RECORDS

Assizes held at Chelmsford 19 July 1654

Dates of Creation 30 June 1654

Scope and Content Indictment of William Lamberd, George Hurill and William Smyth, all of Stisted yeoman, there riotously assembled and broke an iron chain worth 10d. and a wooden gate worth 8s., belonging to John Alston. Witnesses: John Alston, Lestrange Alston, Anne Alston, John Grigg. [ASS 35/95/2/22]

(It is assumed this is John Alston of Stisted)

Reference: T/A 418/144/23

CALENDAR OF ESSEX ASSIZE RECORDS

Calendar of Essex Assize File [ASS 35/95/2] Assizes held at Chelmsford 19 July 1654

Scope and Content:

Indictment of Rob.Aylett, Robert Wood, John Wood, William Lambard, Thomas harris, George Hurrell, all of Stisted yeoman, John Smith of Bocking, John Wodle and Isaac Medroppe of Stisted yeoman riotously assembled at Stisted and broke a wooden gate worth 8s.6d. belonging to John Alston. Witnesses: John Lestrange, Anne alston. [ASS 35/95/2/23]

Dates of Creation:

20 April 1654

Essex Record Office Q/SR 367/93

Not dated: between 1654 - 1656

COURT IN SESSION: SESSIONS ROLL EPIPHANY 1656

Scope and Content: PETITION of the inhabitants of Toppesfield reciting that Katherine Boreham . . . . .

Signatures . . . . . John Alston, William Butcher, William Edwards, James Smyth, John Edwards, Matth. Edwards, John Scott, Thomas Bo(?d) ham, Edw.

Essex Record Office D/DGd/T61

67 SPERLING FAMILY OF DYNES HALL, GREAT MAPLESTEAD

Dates of Creation 1615-1768

Scope and Content: . . . . . and attested copy, 17th cent., of attested copy [n.d.] of will, 1653, of John Alston of Stisted, gent. Deeds of mansion on house called Cusee Hall, with dove-house, barns,

stables, yards, orchards, gardens and land (85a.) [field-names], 1615-1707; deeds, 1641-1700, including messuage called Colemans with land (43a).[field-names]; manor house called Hosyes alias Houses, with buildings, yards, gardens, orchards and land (157a.) [field-names], 1617-1709; deed 1676, including cottage with windmill, stable, yards, gardens and ground (1a); messuage called Crophall, with outhouses, yards, gardens,backsides and land (3a.) abg. on King's highway from Cusshall to parish church, Toppesfield, 1684-1707; land (42a.) [field-names] copyhold of Manor of

Barwicks and Sootneys, 1678-1703; and 3 pieces of land (4a.) copyhold of, manor of Stoke-juxta-Clare, 1706-1722 Incl. valuation, 1768, of farms called Abbots and Gurtens in Haverhill.

Near contemporary copy of Probate copy, m1586, of will, 1586, of William Bigge of Toppesfield, yeo.; and attested copy, 17th cent., of attested copy [n.d.] of will, 1653, of John Alston of Stisted, gent. 1615-1768

QUOTE FROM THE BOOK "SMALL BEER BY URSULA SIMSON" AN ESSEX VILLAGE (STISTED) FROM ELIZABETH I TO ELIZABETH II.

No publication date - page 13

. . . . . large and wealthy family in the village was that of ALLSTON. The name appears first in the Register of 1636, when Thomas ALLSTON, gent., was buried. During the rest of the century they are very much in evidence. There appear to have been two branches of the family, for one lied at Kentish Farm and the other at Milles, and it si quite impossible from the Register to disentangle them. There was a Henry ALLSTON who signed the Register as Church Warden in 1648, and in view of his office it seems likely that it was he who tried to influence the course of events in 1644, by offering 10pounds ti Mr. Joslin of Earle Colne, when he, (Joslin), was trying to arbitrate in the dispute about the appointment of the Rector.

Then there was John ALLSTON of Kentish Farm. He appears first in 1654 presented at the Quarter Sessions on two charges: firstly, for "allowing the ditch on both sides of the Highway leading from Cock Pierce Bridge towards Rayne Hatch to be unscoured, which ought to be cleansed by him, by reason of his tenure of the land adjoining the said ditch" and also because "he hath wilfully suffered divers boughs of his trees to overhand the Highway on both sides there leading from Cock Pierce Bridge towards Rayne Hatch, whereby the Highway is so dirty that people cannot pass".

The witness in both these presentments was Robert Aylett, who lived at Rayne Hatch. He evidently felt strongly about this as the Highway in question was his road from Rayne Hatch to the village.

John ALLSTON died in 1656, leaving his very considerable estates in Stisted and Bocking to his eldest son L'Estrange ALLSTON. The only other noticeable thing in his will is his bequest of 1s only to Henry , his youngest son but one, without explanation or comment. Perhaps he was an unsatisfactory character. L'Estrange was in trouble some years later for obstructing a watercourse in common footpath running from Rayne Hatch to Woolmergreen. (Essex RO Q/SR 408/20)

Of the other branch of the family nothing appears to be known, except that John ALLSTON of Milles died in 1658. It was possible he who four years earlier was in trouble for "disannulling an ancient footpath leading to the Church and laying out another way in room of it, to the prejudice of the inhabitants of the Parish and the towns adjacent" . It was at that end of the village where his lands lay." . . . . .

Ref: Susan Perrett 2009.

From the book of Toppesfield, showing John Alston's Belchamp Otten connection

THE MANER OF HUSEES.

Roger, son of John Huse, upon the death of John de Berewyk in 13 12, inherited this estate, to which he gave name. This Roger sprung from the ancient family of Huse in Wiltshire and Dorsetshire ; was a great soldier ; became a knight; had summons to Parliament in 1348 and 1349, and died in 1361 ; being seated at Barton Stacy, in Hamp- shire. John, his son, succeeded him. In 1419, Alexander Eustace and John Wood sold this estate to John Symonds. He?try Parker, of Gosfeild, Esq. who died 15th January 1 541, held this messuage, called Hosees, and 80 acres of arable and meadow, of John de Vera, Earl of Oxford, in socage ; besides other parcels here, and great estates elsewhere. Roger, his son, succeeded him. William Cratchrode, junior, held this maner in 1585. About the latter end of Queen Elizabeth, it was holden by John Alston, of Belchamp Oton , who gave it to his third son, Matthew ; and and he having no issue, bequeathed it to Thomas Cracherode; of whom it was purchased by Colonel Stephen Piper; and it is now in the possession of Dr. Piper [whose family sold it to Henry Sperling, Esq., of Dines Hall].

Ref: Mary Terbrack 2013.

THE MANOR OF CUST-HALL.

The mansion-house stands near a mile south-west form the church. It took its name from an ancient and considerable familyf which were seated herein King Edward the Third's reign. Afterwards, it became the Cracherode family that had long been settled at a place called from them Cracherodes, in this parish. The first of the name that hath occurred to us, was John Cracherode, witness to a deed, 17th Richard. 1393. His son Robert, was father of John, an Esquire under John de Vere, Earl of Oxford, at the battle of Azincourt. John Cracherode, Gent., son of the latter, married Agnes, daughter and heir of Sir John Gates, of Rivenhall ; and had by her, John ; William, Clerk of the Green Cloth to King Henry VHI, and Thomas, who had to wife Brigett, daughter of Aubrey de Vere, second son to John the 15th Earl of Oxford. John, the eldest son, paid ingress fine for Cust-hall in 1504. He married Agnes, daughter of Tho. Carter; and departing this life in 1534, was buried in the middle of this church, under a grave-stone, with an inscription.

They had four sons and four daughters ; viz., Helen, wife of William Hunt, of Gosfeild, Gent. ; Joan, of John Tendring, of Boreham, Gent. ; Julian, of . . . . . Lee ; and Jane, of Peter Fitch, of Writtle, Gent. William, the only son whose name is recorded, married Elizabeth, daughter of John Ray, of Denston in Suffolk. They lived 56 years together in wedlock. At the time of his decease, 10th January, 1585, he held this capital messuage, called Custs, and 20 acres of free land, belonging of old thereto; also a messuage, anciently called Cracherodes, and afterwards Colman's, in this parish and in Hedingham Sible ; with several other parcels of land ; particularly Albegeons, and Camois Parke, Pipers Pond, &c. He, and his wife, which died 17th February 1587, lie both buried in the chancel of this church, under a blue marble stone. They had issue five sons and one daughter ; viz., Thomas ; Matthew, of Cavendish; John, Charles, William. The daughter, named Anne, was wife of John MooXhdim.- Thomas , the eldest son, married Anne, daughter of Robert Mordaunt, of Hemstead in this county, Esq., a younger branch of the Lord Mordaunt, of Turvey in Bedfordshire; by whom he had William, who died without issue ; Thomas; and four daughters: Frances, married to Robert Wilkins, of Bumsted ; Anne, to John Alston, of Belchamp-Oton ; Elizabeth, to John Fryer, of Paul's-Belchamp, and Barbara, to . . . . . Harris. He died 14th June 1619. - Thomas, his son and heir, then aged 40 years, married Elizabeth, daughter of Richard Godbolt, of Finchamp in Norfolk ; John, of Cranhamhall in Romford ; Richard ; and three daughters : Elizabeth, Brigett, and Susan. Mordaunt, the eldest son, married Dorothy, daughter of Antony Sammes, of Hatfeild-Peverell. He died 2d of February 1666, and she 6th of March 1692. Both lie buried in this church. - They had issue, Thomas, baptized on the 17th of September 1646; Antony; Mordaunt [who was a linen-draper of London] ; and Mary, wife of Christopher Layer, of Boughton-hall, Esq. Thomas, the eldest son, married Anne, daughter of Christopher Layer, of Belchamp St. Paul; by whom he had Thomas, baptized the 1st of June 1680. He was buried in this church the 8th of July 1706. Thomas, his son and heir, sold this maner, in 1708, to Colonel Stephen Piper, mentioned a little before [whose family sold in to Henry Sperling, Esq., of Dines Hall].

Ref: Mary Terbrack 2013

John's Will is dated 30th June 1653, mentions his wife Anne as living, his daughter Mrs. Drury, and his sons John, Matthew and Henry.

Research Notes: Research Notes:

Dr FRANCES TIMBERS - University of Toronto

Liminal language: boundaries of magic and honor in early modern Essex.

Magic, Ritual, and Witchcraft.

2.2 (Winter 2007): 174(19). Expanded Academic ASAP. Gale. Victoria University. 2 June 2009

In 1645, in the small village of Stisted, Essex, two serving maids told the Justice of the Peace that a group of twenty or more men and women had, on several occasions, visited various gentry households where they "conjured" the residents to sleep. This group included leading men of the community, male and female servants, and a "Conjurer, that went in black Apparrell." At the home of John Alston, the master of the two maids, the group dragged the master's married daughter out of bed and two men "had the use of her bodie." Then her husband was fetched and two of the maids "kissed him & puld up his shirt, & took up their Coates & lay downe on the top of him & they said that he did them some good, for he lay with them as man with a woman." They also dragged Alston's eldest son out of his bed and laid him beside his sister. The maids dressed up in some of their mistress's petticoats, while some of the group broke into their master's study and stole money. They even stole malt from their employers to be brewed especially for these meetings. The participants frequently ended these romps by feasting on stolen geese, capons, and venison, while fiddlers from Coggeshall played, or one of the maids entertained them on the virginals. At one such gathering, one of the members of the group was concerned about secrecy and made the participants swear "an oath to keep things secrett" on an unspecified book. Mysteriously, the victims slept through the entire proceedings.

On March 28 and 29, 1645, the two maids, Elizabeth Gallant and Martha Hurrell, gave details of this incident (which took place two years earlier in 1643) to a Justice of the Peace, in relation to a Quarter Sessions investigation of the event. At the next Quarter Sessions, Midsummer 1645, four of the people named in the depositions submitted a petition to the Justice to drop the related allegations. There is no surviving record of an indictment to indicate that formal charges were ever made following the investigation. The depositions indicate that sexual misconduct, theft, and conjuring were all elements of the incident in question. Several prominent families of the parish were involved in this legal situation. By drawing from other county records, such as court cases and parish registers, I have partially reconstructed the scenario in Stisted in the mid-seventeenth century. In brief, John Alston, one of the leading men of the community, accused Robert Aylett and his compatriots of invading his home. They dragged his son, his daughter, and his daughter's husband out of their beds and assaulted them. Then they broke into his study and took money. All of this was accomplished by "conjuring" the residents to sleep. (1)

The accusations against the Aylett group grew out of the fact that John Alston had lost some money out of his study. In order to identify the thief, he and his wife consulted a cunning-man, whom they paid 40 pence. The cunning-man confirmed that it was Robert Aylett and his confederates who broke into the study and stole the money, while Aylett charmed the household asleep. In Martha Hurrell's first deposition, she confirmed that another one of the maids, Elizabeth Waite, opened the study door with a "picklock," allowing Robert Aylett and three other men to enter. Alston, however, was not content with a simple charge of theft against the group. In addition to allegations of rape and physical assault, he also accused Aylett of using ceremonial magic. Gallant's first deposition included details of the magical ceremony. She alleged that the conjurer cast a circle in her master's hall and set up three candles, which burned blue. The group extinguished the candles with milk and soot. (2)

The historian can approach this narrative from several angles. The entire account could be dismissed as fictitious, merely wild delusions of serving maids trying to cover up a theft by servants; or it could be read as a version of "rough music," the English version of charivari; or it could be taken as an actual attempt at group ceremonial magic. During the alleged events, the Alston men did not attempt to defend themselves or their womenfolk; they were also passive victims. Yet the Alston men were not strangers to violence and confrontation. How could they explain their passivity and still maintain their male honor and their household authority? My assessment of this episode takes its cue from the work of anthropologist Clifford Geertz, who states that, "cultural analysis is . . . . . guessing at meanings, assessing the guesses, and drawing explanatory conclusions." (3) Speculation is often useful in attempting to grasp the hidden meanings inscribed in premodern narratives.

My approach to this incident grew out of my larger research on how the practice of ceremonial magic validated or undermined the ideologies of gender. (4) I consider gender ideologies as animating conditions and magic as a function of social arbitration. I argue that in this instance the alleged use of ceremonial magic constructed a liminal space wherein the victims were not responsible for their actions, or lack thereof. This offered the Alston family, both male and female, an opportunity to salvage its honor. The language of liminality, which is embedded in ritual magic, can serve many purposes. In this instance, it was a mechanism for the resolution of social conflict. In the seventeenth century, the boundaries of a ceremonial magic circle created a liminal space that protected the participants from demonic spirits. It was a safe container, temporarily removed from the profane world. In the incident under examination, several normal social boundaries were transgressed. The boundaries of John Alston's household were trespassed; his home was overtaken and his study was broken into and robbed. Boundaries of social status were transgressed; the Alston's servants engaged in subversive and disrespectful behavior. Sexual boundaries were broken; Elizabeth Drury was raped or, at the very least, shamed and dishonored. Gender boundaries were disrupted; Edmund Drury was sexually inverted by being mounted by the women and raped - a truly feminized victim. The normal world of Stisted was turned upside down. However, the Alston family's use of a narrative that included ceremonial magic constructed boundaries that protected the family's honor.

My methodology combines techniques of social anthropology with a poststructuralist approach that emerged from psychoanalytical methodologies born of French feminism of the mid-twentieth century. This entry point into the texts takes into consideration community relations in which the incident took place, including the social function of ritual in context, while allowing for a close reading of the texts that are a product of the specific social situation. The general conclusions usually gained about a community from a social anthropological methodology are made more intimate by the psychoanalytical approach, which acknowledges the fears and desires of the individual subjects under investigation. Since the 1970s, cultural historians have borrowed methods from anthropologists in order to analyze the meanings behind social and cultural practices. This approach is evident in the work of Keith Thomas and Alan Macfarlane, both of whom construct magical activity in terms of its social function, particularly with respect to the accusation aspect of witchcraft. (5) Anthropologists such as Victor Turner and Arnold van Gennep stressed the importance of ritual as a cultural practice of the society under examination because of the symbolic meanings attached to it. (6) Inversion rituals, such as charivari, are particularly demonstrative of the juncture of order and chaos; they provide a space for the culture to reinforce the norm, while delineating the unacceptable elements of the society. (7) As Catherine Bell points out, however, participants in the ritual do not consciously take their social problems to ritual with the expectation of resolution. Nevertheless, the nature of ritual sometimes allows participants to manipulate the social elements to arrive at a solution without ever really defining the problem. (8)

Ritual magic is also an intersection where diverse social and cultural forces meet and interact, including the real and the imagined. In combination with a social anthropological approach, a linguistic and psychoanalytical approach facilitates a reading of the texts that understands that a person's life takes on meaning through the narratives that she or he constructs about her or his life experiences. (9) How and why the text was constructed informs the historian of the subject's fears and desires, as well as broader cultural concerns. This approach acknowledges the importance of the role of the imaginary realm in a person's construction of self-identity. The fears and desires of the storyteller are inherent in the narrative and can be unraveled through a careful reading of the text. (10) Instead of dismissing the fantastic elements of the text, I consider them to be integral to the narrative.

An anthropological methodology necessitates knowledge of the community and its members. Relationships between the accusers and the accused are integral to understanding the tensions that give rise to accusations, as well as highlighting what was important to members of that society at that particular moment in time. The parish of Stisted is situated in the Hundred of Hinckford, in the County of Essex, in the area known as East Anglia. It is two miles northeast of Braintree on the river Blackwater, approximately forty-two miles northeast of London. One of the main manors in Stisted was the manor of Rainhatch, which straddled the parishes of Stisted, Braintree, and Bocking. It had been in the possession of the Aylett family since at least 1583. The Ayletts were an old, well-established gentry family in Essex county, dating back to the time of King Henry II (1154-89). In 1433, Richard Aylett was considered the chief gentleman of the county. Two of the principal men accused by the Alstons in 1645 were directly descended from this prestigious lineage. Robert Aylett (b. 1615) was the eldest son and heir to the manor of Rainhatch. Thomas Aylett (d. 1659) was his younger brother. Eventually, Robert married at the relatively late age of fifty and produced one male heir, but in the 1640s he was unencumbered by dependants and was not the official patriarchal head of the Aylett family. In early modern terms, he had not yet achieved full manhood, which was partially determined by being married and becoming the head of a household. (11)

John Alston (d. 1653), the main protagonist in this drama, was described as a gentleman and a major landowner in the area. His first born son, Lestrange, was born in 1600, which suggests that John was in his seventies by 1645. (12) In the 1636 Ship Money assessment, his allotment was valued at four times the value of the Robert Aylett estate. (13) At the time he wrote his will in 1653, he held land in Stisted, Bocking, Boxford, Toppesfield, Weathersfield, and Sible Hedingham, as well as in Ladley in Suffolk. (14) Evidence reveals that there was an ongoing competition between the Ayletts and the Alstons in relation to their standing in the community.

The maids, Elizabeth Gallant and Martha Hurrell, worked for John Alston. They each gave depositions on March 28, 1645, and then retracted and modified them the next day, on March 29. The substance of the two depositions varied greatly. In the first set of statements, they alleged that a group of twenty or more men and women had, on several occasions, visited various gentry households where they "conjured" the residents to sleep. This group included Robert and Thomas Aylett, other leading men of the community, male and female servants, and a "Conjurer, that went in black Apparrell, of a browne haire, & a blackish beard, a man of a middle size." The incident in question supposedly happened at one of half a dozen meetings held at the Alston's home. Apparently, similar romps had taken place at the home of other leading gentry families in the area, including Sir William Maxie's, (15) Lady Eden's, (16) and Sir Thomas Honniwood's. (17) Sexual misconduct was an element of the proceedings at the other locations as well, including pulling Lady Maxie out of her bed and pulling her smock up to her waist, as well as "using" Sir Honniwood in the same manner as Edmund Drury. (18)

Although the maids retracted much of their testimony on the second day, they reiterated some of the details. First of all, the names of the participants changed drastically. The Aylett brothers were specifically vindicated and two of the men who remained accused were described as being "base borne." In other words, the social composition of the group was altered from the Alstons' gentry rivals to a handful of rabble and servants. Hurrell also denied ever being at the homes of the other gentry families. At first this appears to be insignificant, but the inclusion of other high-ranking families as fellow victims had, no doubt, alleviated some of the shame from the Alston family. If similar events had happened to other respected families then that meant that the Alstons were not singled out for derision. (19)

The elements that were retained in the second version of the narrative are of particular interest. Martha Hurrell reaffirmed that Elizabeth, John Alston's daughter and the wife of Edmund Drury, was indeed taken out of her bed and "laid in the hall chamber, & then John Bayliffe would have abused her, (& that he took up her smock as high as her wast [sic]) but was prevented by the rest of the Companie." In both of the statements, Elizabeth Drury's brother, Lestrange Alston, was laid beside her; however, there is no elaboration of sexual activity by the maids in the revised version. Also, it is never stated whether Elizabeth Drury was awake or asleep during the attempted rape. So in both versions of the event, John Alston's married daughter was dragged from her bed and in some way sexually assaulted. And in both versions, the Alston men did nothing to protect her; in fact, they were passive victims as well. In both accounts, John Alston was "puld about . . . . . as he lay in his bed," but one of the maids, Elizabeth Gallant, prevented the group from carrying him downstairs. More importantly, there is no conjuring or magic mentioned in the second version of the story. This is of utmost importance to my argument--the element of conjuring was only a part of the narrative in the first version, the version endorsed by the Alstons themselves.

According to the maids, the Alstons and Drurys insisted that they recount the first version of the events. They alleged that they had been coerced by John Alston and his wife, Anne, as well as by Edmund Drury and his wife, Elizabeth, into accusing the Aylett party. Elizabeth Gallant said that Mrs. Alston followed Martha Hurrell around threatening her with a beating and if "she did not acknowledge what they charged her with (which was that before) she should answeare it in a worse place." Gallant even said that the Alstons would not let her go out of the house for fear she would tell the truth. But the day following their initial deposition, the girls were free from the intimidation of their masters and were determined to set the record straight. Given the maids' social position and the Alston family's reputation for violent behavior, it is not surprising that they were reticent to disobey their employers.

It appears that there was an on-going feud between the Alston clan and the Aylett family, or possibly between the Alstons and everyone else in Stisted. There had been several altercations throughout the years between John Alston and his sons, and the rest of the community. Twenty-six years before this incident, in 1617, John and his eldest son, Lestrange (only seventeen years old at the time), were ordered to keep the peace against certain men of the parish. (20) Shortly after the conjuring accusation, in 1652, the Alstons stirred up the community against paying rates for the troops during the civil war. During the investigation, it was revealed that the Alstons "have ever bin refractory in the payment of any some or somes they have bin rated att" and had refused to pay the last rate as well. (21) Later that year they were in conflict with the law again, complaining that they were being overrated for poor rates as well. (22) The first petition, concerning rates for the troops, was initiated by the constables of Stisted, one of whom was Robert Wood. (23) In January of 1654, Henry Alston, the youngest son of John, apparently got his revenge against Wood. Henry was found guilty of beating Wood so severely with "swords staves & knyves" that "of his life it was greatly dispaired." (24) But a few months later the tables were turned once again, as Wood, along with Robert Aylett and other Stisted yeomen, "riotously assembled" and broke a wooden gate of John Alston's. Alston must have been enraged that the jury returned the indictment as "not a true bill." (25)

This was at the same time as Henry Alston and Robert Aylett were involved in a dispute concerning payment of a fine by John Alston. In 1653 Henry Alston had been one of the overseers for the poor. Although the parishioners of Stisted had nominated Robert Aylett, along with two other men, to replace him in 1654, Henry continued to consider himself the official overseer. Meanwhile, Henry's father John was convicted for swearing several oaths and was ordered to pay a fine of twenty shillings. When Aylett and the other overseers endeavored to collect the fine, John Alston maintained that he had already paid it to his son, Henry. This case was also settled in favor of the Aylett faction. (26) The feud was still active ten years after the conjuring incident; Robert Aylett complained to authorities that Alston had failed to either scour the ditches or trim the branches back from his portion of the highway. (27) These incidents paint a picture of the Alston men as irascible, uncooperative, and aggressive. It also illustrates how an early modern community sometimes took the law into its own hands. The community rivalry was played out by passive civil disobedience, recourse to legal authority, and outright violence.

A common method of self-regulation within a community was the charivari, or "rough music," as it was known in England. Indeed, this incident could be read as an example of charivari, although the specific reasons behind it have been obscured. E. P. Thompson stresses that there were many variations of the ritual and impromptu improvisations. Some of the usual elements included masking, dancing, raucous or discordant music, and the "riding" of the victim upon a pole or donkey. These incidents often included both the middling sort and the "ruder" members of plebian society. There were many reasons for an episode of "rough music" in the early modern era, including a woman overruling her husband or beating him, unfaithfulness by a woman that went uncontested by her husband, generally licentious conduct of a married couple, or extreme cruelty by a man toward a woman. Incidents were often part of factional conflicts, like this minidrama between the Alstons and the Ayletts. Historians have also found that the particular event that was the focus for the charivari, such as sexual incontinence, was not usually the only grounds for the community's reaction. There were often other factors that had aroused community angst against the targeted couple or individual. (28)

Joan Kent documented an episode of "rough music" in Burton-upon-Trent, Staffordshire, in 1619, in which the victims were verbally and physically assaulted, as well as being imprisoned in the stocks. When the couple eventually returned to their home, they found that a chest had been broken open, and 5 [pounds sterling] and other household goods had been stolen. Whether this was part of the charivari or the actions of an opportunistic thief is not clear, but it demonstrates the extremes to which these episodes could go. This could help to explain how the incident of theft became associated with the sexual assault charges in the Alston case. "Rough music" was used not only to mock and shame the victims but was a means of punishing offending members of the community, and perhaps of recovering what some members thought was rightfully theirs. (29) But if this particular episode had started out as a shaming ritual, that would give even more reason for John Alston and his household to attempt to rectify the inversion.

Passive submission is usually part of the popular custom of "rough music." In the face of the entire community, the victims have little other choice but to submissively accept their punishment. One of the most outrageous elements of the narrative that was endorsed by the Alstons was the mounting and symbolic rape of Edmund Drury. The "woman on top" scenario is the ultimate symbol of sexual inversion. Victor Turner originally constructed "rituals of status inversion," such as the charivari, as a tool for reaffirming the order of social structure. But Natalie Zemon Davis has argued that sexual inversion could also undermine traditional hierarchies by blurring and reversing social boundaries. (30) "Riding the stang" or the parading of the victim on a pole was often part of an episode of "rough music." This was particularly relevant when the offense was wife-beating. One of the men in the group would dress as a woman and beat the victim, or his surrogate, with a distaff or skimming ladle. The "riding" of Edmund Drury was an even more explicit display of shaming. As both the husband and the wife were pulled out of their beds and sexually assaulted, it would seem that both were being targeted for some sort of sexual or social transgression. Another interesting element is that, in both versions of the narrative, Elizabeth's brother, Lestrange, was also pulled out of his bed and laid beside his sister. What role did he play in the family's disgrace?

E. P. Thompson interprets the charivari as a form of street theater. (31) This fits well with Victor Turner's theory of ritual as a form of social drama. Following van Gennep's three stages of ritual, Turner suggests that there are three stages to social drama: the breach of a societal rule or custom, the actual state of crisis, and redress by authority. (32) During the final stage of a social drama, an interpretation of the crisis is constructed that gives meaning to the event. Before the narrative is fixed, there is a state of indeterminacy, or liminality, which exists as a state of potentiality. (33) The person, or in this case the group of people, in this liminal space are between the worlds. They are temporarily not subject to the usual laws and conventions of society. In formal rituals, the liminal initiates become a community of undifferentiated individuals, without reference to social status. In this informal "ritual of status reversal," there was no division between servants and masters. Lesser gentry males and serving girls interacted as equals. Boundaries of social status and gender were both elided. Another characteristic of liminality is that the underling becomes uppermost. The structural inferiors, in this case the young female servants, symbolically take on the behavior of their structural superiors, in this case the older male masters. This is certainly evident in the maids' "riding" of Edmund Drury, as well as in the maids' dressing up in the clothing of their mistress. (34)

In an organized "ritual of status reversal," such as carnival, the more powerful members of the society patiently endure the aggression of their inferiors. Their reward is that the absurdity and paradox that arises from the ritual serves to underline the norm, which leads to the restoration and maintenance of the status quo. (35) Normally, inversion rituals provide a space for the culture to reinforce the norm while marking out the unacceptable elements of the society. Even in semi-organized rituals of inversion, such as charivari, the victims are expected to accept their humiliation as retribution for their transgressions. But perhaps John Alston did not humbly accept either his guilt or his punishment. By including the element of ritual magic in the narrative, a different kind of boundary was established that counteracted this temporary spontaneous inversion. A circle was cast that physically overlapped with the Alstons' household but created a psychic space outside of secular time and space.

We know that the boundaries between the "real" and the supernatural in the early modern world were permeable; ghosts, angels, and demons could easily transgress these boundaries. (36) But ceremonial magic purposely created a container that was "betwixt and between" the worlds. By constructing such a magical space through the narrative, the Alstons felt that it was safe to make accusations against their aggressors that otherwise would have been shaming or derogatory to themselves. The Alston family not only constructed a narrative that could give meaning to this particular social drama, but the narrative also allowed them to extract meanings that were disturbing to the participants. Instead of being considered as a passive bystander who allowed his home to be robbed and his daughter to be raped, John Alston could configure himself as a victim of supernatural power, beyond human contestation. This construction may not have been a conscious effort, but the fear of dishonor and sexual assault led the Alston family to unconsciously modify its narrative using material from shared cultural artifacts. The legal proceedings that produced the narratives contained in the historical texts reflect Victor Turner's third phase of social drama, wherein the narrative cements the meaning of the event for the participants. (37)

According to the maids, it was Elizabeth Drury (Alston's daughter and the assault victim) who followed the maids about "putting these things [the allegations in the first deposition] to them." Elizabeth Drury's husband, Edmund, had attended Christ's College at Cambridge University in 1625. (38) Cambridge had been a center of puritanism in the sixteenth century, and Christ's was the most radical college. Although there were more royalists than puritans enrolled in 1643, the college still had a reputation for its puritan outlook. (39) This reputation must have been somewhat tarnished by the group of philosophers known as the "Cambridge Platonists" led by Henry More, a student of Christ's in 1631 who studied kabbalah and believed in witchcraft. (40) Nevertheless, whether a seventeenth-century university student was on the side of Calvinism or Platonism, natural philosophy, including ceremonial magic, was a popular subject of debate. In fact, St. John's College, Cambridge, produced several magicians. The study of cosmography, which included astronomy and astrology, was encouraged as extrastatutory curriculum at Cambridge by tutors such as Thomas Allen (1540-1632), an intimate friend of John Dee, and reputed as another Roger Bacon. (41) Ritual magic had been transmitted and maintained during the late medieval period by the monastic and university communities. As a university-educated man, Edmund Drury would have been more familiar with this discourse. If he had Calvinist leanings, he would have viewed the practice of magic as papist. Perhaps it was he who introduced the idea of ceremonial magic to the Alstons as a strategy of defence.

There is some tenuous evidence that the Alstons leaned toward the religious left. Ralph Josselin, the godly minister of neighboring Earles Colne, commented in his diary that the men of Stisted consulted him concerning their selection of a minister in October 1644. Josselin was firmly on the side of parliament in the civil war. He served as a parliamentary army chaplain, raised funds for the parliamentary troops, and frequently prayed for success against the king's forces. He reported that the town of Stisted was alienated over who should be chosen as minister, "both parts stiffe; divided, a most sad towne, no care almost of any thing." His observations of the town support the theory of a feuding citizenship. Josselin noted that the men "would not condiscend [sic] one to another." It appears that the Alston men, in particular, preferred a more Calvinist approach to religion. One of the Alston men offered Josselin 10 [pounds sterling] out of his own purse "if [Josselin] would yeeld to them." Two years after this incident, Josselin traveled to Stisted to baptize an Alston baby. (42) Nevertheless, in 1652 Henry Alston stirred up a crowd in the churchyard concerning charges by the parliamentary troops "for drums and culls'es." (43) Apparently, matters of the soul did not override matters of the pocketbook.

Regardless of religious and political stance, Edmund Drury's wife, Elizabeth, had more invested in an alternate scenario than the others. Early modern rape victims were overwhelming concerned with their reputations. Men defined rape as a sexual act (as opposed to an act of violence), and the normal discourse concerning women and sex was one of acquiescence. Despite the fact that women were considered the lustier sex, they were constructed as being submissive during the act of intercourse. It was because they were lusty that they acquiesced. Garthine Walker argues that in order for stories of rape to stand up to male scrutiny, the element of female submission had to be absent. Any language of acquiescence implicitly fostered the idea of consent. One way to prove the absence of submission was by the demonstration of resistance. Too much resistance, however, could undermine the woman's reputation and construct her as a disorderly woman. (44) Yet neither consent nor resistance could be offered if a woman was "charmed" asleep and oblivious to the proceedings. Her honor could hardly be impugned if she had no agency whatsoever. Through the construction of the ceremonial magic narrative, Elizabeth Drury was able to transfer her agency, or lack thereof, to her assailants and her male relatives. Her hounding of the maids reveals her concern about the reconstruction of the event. (45)

The shift of attention from rape to magic protected more than Elizabeth Drury's honor. While it effectively removed from her any notion of complicity in the sexual scenario, it also protected the honor of her male kinsmen. Control over the household, and particularly, control over the sexual activities of wives and daughters, was an important element of male honor in this period. Men who did not defend their wives and families risked their status in the social order. (46) As one of the leading men in the community, John Alston had to maintain his position as patriarchal defender. His need to defend his position in the household may also have been affected by his advancing age. (47) Edmund Drury's reputation as a husband was also at risk. Not only had the men not defended Elizabeth Drury against attack, they had also been victims. In the first version of the events, the one endorsed by the Alston faction, John Alston was taken out of his bed and laid "upon a Coffer att his bedd feete." The group would have carried him downstairs along with the others except the maid, Gallant, persuaded them otherwise. Even in the second version of the story, Martha Hurrell averred that one of the men "was verie desirous to take her Master out of his bed & to carrie him downe." In both versions, John Alston was defended by one of his serving maids, yet another inversion of gender and social hierarchy. If Alston and the other men were not conjured asleep, how could they explain their submission to such behavior and still maintain their male honor?

If John Alston chose to frame the accusations of theft in terms of the supernatural, why did he choose ceremonial magic rather than witchcraft? Coincidentally, in 1589, when John Alston was a young man, Alice Aylett, wife of Thomas Aylett of neighboring Braintree, had been charged with being a witch and enchantress. Therefore, the Aylett name had already been associated with witchcraft accusations. (48) However, witchcraft in England was usually concerned with maleficium; theft and rape were outside its jurisdiction. Also, Robert Aylett did not meet the English stereotype of a witch as a poor, elderly woman. There are several examples of men of higher standing being charged with witchcraft. The profile of John Alston that has been sketched out here, however, is of a man who was proud and competitive. If his household was going to be conjured asleep, it was not going to be by just any common witch.

The construction of Robert Aylett as a powerful conjuror both strengthened the Alston household's position as victims and bolstered John Alston's honor. It is one thing to overcome the weak will of a woman, but to overcome a strong man's will takes a powerful magus. Robert Aylett's family was the chief rival of the Alston family in the parish. By accusing Aylett of conjuring the Alston household to sleep, Alston was inadvertently acknowledging the status of his opponent. Although the image of the magus was generally disintegrating during the last half of the seventeenth century, the power of magic was still held in awe. For example, the Alstons had no scruples about consulting a cunning-man for advice concerning the theft. Although Alston had been temporarily humiliated by Aylett's magic, he could turn the tables on his opponent by exposing his sorcery to the world. This not only salvaged Alston's honor in relation to his passivity but had the potential of dishonoring his rival. Magic provided a further discourse in their on-going competition for status in the community.

The background noise of England between 1643 and 1645 was a civil war, which divided the country along political and religious lines. As previously noted, the parish of Stisted was divided concerning the appointment of a minister during this period, which indicates some sort of religious rift. Generally, the county of Essex was a parliamentary stronghold; the county militia of the Eastern Association was particularly strong, although no area was strictly pro- or antiroyalist. The Quarter Sessions of 1645, when the justice examined the serving girls, were held before the decisive battle of Naseby, in which Cromwell defeated the royalists. Therefore, the outcome of the hostilities was cloudy, at best. (49) Josselin reports many days spent in prayer against the king's forces and expresses fear that Prince Rupert's troops would invade Essex after the battle of Newark. (50)

The background of civil war contributed to another reason why the Alstons may have chosen magic as their medium of accusation. The accused Ayletts, Robert and Thomas, were cousins to Dr. Robert Aylett, who had theological and legal training from both Cambridge and Oxford universities. Fifteen years before this event, in 1628, Archbishop Laud had appointed Dr. Aylett to the court of high commission in order to implement Laud's religious reforms. Aylett had particular responsibility for his home county of Essex, which was renowned for its radical Calvinist promoters. Dr. Aylett was one of several of Laud's contingent involved in impeachment proceedings in February 1641, although he personally escaped formal action. (51) Laud's reforms to the Anglican Church were widely interpreted as a return to Catholicism. On Laud's day of execution, Josselin described Laud as "that great enemy of the power of godlynes, that great stickler for all outward pompe." (52)

Catholicism and popery were frequently associated with magic in early modern England. Although there is little evidence that accusations of witchcraft and magical practice were a function of confessional divergence between Protestants and Catholics, there is ample evidence that Protestant England constructed Catholic priests as no better than magicians and sorcerers. In post-Reformation England, there was a near-universal association between the Church of Rome and the Antichrist. The religious underpinnings of the civil wars further reinforced this discourse. (53) Perhaps Alston felt that the accusation of magic would be particularly believable when applied to the cousin of one of the leading men in the county, a man who was an overt Laudian supporter. Regardless of Alston's personal proclivities, this strategy would be especially effective against the backdrop of a civil war defined in terms of religious sentiment, in a county that was severely anti-Laudian and proparliamentarian.

After a century of antipopery, the English population had bought into the Reformation rhetoric of the debauched Catholic cleric. As Lyndal Roper points out, Protestants often accused Catholic priests of sins associated with hypermasculinity, such as drinking to excess and seducing women. As Catholicism became demonized by Protestant rhetoric, the priest became the sorcerer. (54) This model of masculinity was juxtaposed to the Protestant ideal of the "real man" who was head of his household and master of his wife, children, and servants. (55) By accusing Robert Aylett, an unmarried man who had not yet achieved full manhood, of sorcery, John Alston was implicitly associating him with images of the debauched cleric. Whether or not Aylett actually had royalist or Catholic leanings, the imagery could still be subconsciously effective. Alston was taking advantage of the vast polemic literature that associated the Laudian version of the Anglican Church with Catholicism and the Antichrist. Moreover, in gender terms, Alston's construction of Aylett as a conjurer was antithetical to Alston's construction of himself as a Protestant married householder, a position that was quickly slipping away from John Alston, whose servants were in cahoots with the enemy in attacking his house and his family.

This speculative analysis of the Alston and Aylett microdrama reveals that the discourse of magic could be used to reinforce and protect gender ideologies. The social conflicts in this situation, which are animated by gender ideals of honor, hierarchy, and sexual reputation, were mediated through the narrative constructed by the Alston family. Postmodern psychoanalytical theories acknowledge that "self " is not a stable entity but an ongoing autobiography that the person constantly rewrites. (56) In this instance, the Alston family negotiated a narrative that salvaged its reputation and reinforced the family's subjective identity as honorable, upstanding members of the community. The Alstons's gendered preoccupation with honor interfaced with the anthropological function of ritual as a locus for resolving social conflicts. The residual texts that were produced from this discourse represent the production of a narrative that assigned meaning to the events for the participants. The texts can subsequently be deconstructed by the historian to reveal deeper cultural meanings.

Ritual magic proves to be a particularly apt lens to reveal cultural meanings because of its obsession with boundaries. Traditionally, inscribing a circle around something was a claiming ritual, as in the case of rogation ceremonies. The person or persons making the circumambulation marked a boundary and took possession of what lay inside that boundary, symbolically protecting it from external harm. (57) In this instance, the Alstons figuratively and symbolically cast a circle in an attempt to salvage their honor and reputation. Paradoxically, by constructing a ceremonial circle their household was vulnerable inside its boundaries; but, at the same time, the casting of this liminal space constructed a narrative that restored the family's honor, if not its safety.

FRANCES TIMBERS

(1.) This incident is referred to in "Appendix I" in Alan Macfarlane, Witchcraft in Tudor and Stuart England (Prospect Heights, Ill.:Waveland Press, 1970), 306-7. Unless indicated otherwise, all details from the incident are drawn from the depositions in the Essex Record Office (ERO), Quarter Session Rolls, ERO Q/SR 324/118-119.

(2.) ERO Q/SR 324/118-119.

(3.) Clifford Geertz, "Thick Description: Toward an Interpretive Theory of Culture," in Geertz, The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays (New York: Basic Books, 1973), 20.

(4.) Frances Timbers, "From Faustus to Fortune-telling: Gender and Magic in Early Modern England" (Ph.D. diss, University of Toronto, expected 2008).

(5.) Macfarlane, Witchcraft in Tudor and Stuart England; Keith Thomas, Religion and the Decline of Magic (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1971).

(6.) Victor Turner, The Ritual Process (Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company, 1969); Arnold van Gennep, The Rites of Passage, trans. M. B. Vizedom and G. L. Caffie (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960).

(7.) Natalie Zemon Davis, "Women on Top: Symbolic Sexual Inversion and Political Disorder in Early Modern Europe," in The Reversible World, ed. B. A. Babcock (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1972); E. P. Thompson, Customs in Common (New York: The New Press, 1991).

(8.) Catherine Bell, Ritual Theory, Ritual Practice (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), 16, 106.

(9.) This approach is evident in the work of Natalie Zemon Davis, Fiction in the Archives: Pardon Tales and their Tellers in Sixteenth-Century France (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1987); Lyndal Roper, Oedipus and the Devil: Witchcraft, Sexuality, and Religion in Early Modern Europe (London: Routledge, 1994).

(10.) Psychoanalytical concepts are adapted from Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, trans. Leon S. Roudiez (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982).

(11.) In 1658 when Robert the Elder died, Robert the Younger inherited the manor of Rainhatch. Robert the Elder of Stisted (d. 1658) was the second son of Robert of Coggershall and a daughter from the Thorowgood family. He married Elizabeth Barrows (or Burroughs) of Boxford, Suffolk. Robert the Younger of Stisted was their first son, born 1615. He married Mary Hawes of Stisted in July 1665 and had one son, also named Robert, in 1666. Edward Mott was also among the accused. Edward was married to Dorothy Aylett, sister to Robert the Elder, which made him an uncle to Robert the Younger. See Walter C. Metcalfe, ed., The Visitations of Essex, 1634 (London: 1878) (no pagination; entries listed alphabetically); Philip Morant, The History and Antiquities of the County of Essex, Compiled from the Best and Most Ancient Historians, from Domesday-Book, Inquisitiones Post Mortem, and Other Valuable Records, 2 vols. (London, 1768), 2:393.

(12.) This estimate is based on an approximate age of twenty-five at the time of marriage. John Alston was the son of William Alston of Newton and his wife Elizabeth. His wife, Anne Crachrood of Toppesfield, had given birth to at least seven children during their marriage. The three children that concern us are the eldest son, Lestrange, born in 1600; Henry, the fourth (and youngest) son; and Elizabeth, wife of Edmund Drury. See ERO D/DGd/T61, Will of John Alston of Stisted; Metcalfe, Visitations of Essex, 1634.

(13.) ERO T/A 42/1, Ship Money Assessment.

(14.) ERO D/DGd/T61, Will of John Alston of Stisted.

(15.) Sir William Maxie was the second son of Anthony Maxie of Bradwell and Dorothy Bassett. He married Helena Greville of Hareles Parke, Essex, with whom he produced at least nine children. He matriculated as Fellow-commoner from Queen's College in Cambridge in 1583 and was knighted on September 5, 1617. He died on July 24, 1645, at the age of eighty-eight, making him eighty-six years old at the time of the alleged event. See entry on Maxie in Alumni Cantabrigienses: A Biographical List of All Known Students, Graduates, and Holders of Office at the University of Cambridge from the Earliest Times to 1900, ed. John Venn, 2 parts in 10 vols. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1922-54) (entries arranged alphabetically); Metcalfe, Visitations of Essex, 1634.

(16.) Lady Eden may be the wife of John Eden of Ballingdon, esquire. John Eden was the son of Sir Thomas Eden of Sudbury, Suffolk, and Mary Darcy, daughter of Bryan Darcy of Essex, esquire. John married Anne Harlackenden of Earles Colne. They had a son, Thomas, also of Ballingdon, who was a barrister of law in 1664. See Metcalfe, Visitations of Essex, 1634.

(17.) Sir Thomas Honniwood was a Justice of the Peace for the Quarter Sessions by 1657.

(18.) ERO Q/SR 324/118-19.

(19.) There may be another reason for including these particular gentry families. Diane Purkiss suggests that the general disorder of civil war provided an excuse for vandalism by the "lewd and disorderly" sort against the richer members of society. Attacks were originally made against Catholic families but Protestant households were also plundered. The families who were targeted were often already disliked in the community. See Diane Purkiss, The English Civil War: A Peoples History (London: Harper Press, 2006), 132-33. Ralph Josselin also reported that poor people plundered papist homes. In the context of the civil war, "papist" could mean Laudian Anglican. However, two of the families that were named as targets in the conjuring incident, the Edens and the Honniwoods, were staunchly parliamentarian. Josselin recounts praying with Lady Eden and Lady Honniwood against the king's forces. See Alan Macfarlane, ed., The Diary of Ralph Josselin 1616-1683 (London: Oxford University Press, 1976), 13-15. If John Alston wanted to construct the attack on his household as an attack on proparliamentarian families by Laudian sympathizers (see below), the inclusion of these well known Calvinist families would support his appeal.

(20.) ERO Q/SR 219/112, 113, Recognizances.

(21.) ERO Q/Sra 2/78, Petition of constables of Stisted.

(22.) ERO Q/SO 1/13 ff 3v, 4r, Order book.

(23.) Wood was also a churchwarden on several occasions. ERO Stisted Parish Registers.

(24.) ERO Q/SR 360/18.

(25.) ERO T/A 418/144/23, Assize Records.

(26.) ERO Q/SO 1/221, f. 78r, 78v, Order Book.

(27.) ERO Q/SR 366/ 30, 31, Indictments.

(28.) Martin Ingram, "Ridings, Rough Music and Mocking Rhymes in Early Modern England," in Popular Culture in Seventeenth-Century England, ed. Barry Reay (London: Routledge, 1988), 167-91; Thompson, Customs in Common, 469-515.

(29.) Joan R. Kent, " 'Folk Justice' and Royal Justice in Early Seventeenth-Century England: A 'Charivari' in the Midlands," Midland History 8 (1983): 70-85.

(30.) Davis, "Women on Top," 152-54.

(31.) Thompson, Customs in Common, 478.

(32.) According to anthropological theories, there are three stages to a formal ritual. The preliminal rites involve separation of the individual from the community; the transitional stage places the person in a liminal state; and the postliminal or aggregation stage reincorporates the person back into the community. It is during the liminal or transitional stage that the social concern (the reason for the ritual) is resolved. Van Gennep, Rites of Passage, 11 and passim.

(33.) Victor Turner, From Ritual to Theatre: The Human Seriousness of Play (New York: Performing Arts Journal Publications, 1982), 75-77, 92.

(34.) Turner, Ritual Process, 95-96, 102, 184.

(35.) Ibid., 176.

(36.) Roper, Oedipus and the Devil, 5.

(37.) Turner, From Ritual to Theatre, 75-77.

(38.) Edmund Drury (1607-68), was the son of Francis of Swaffham Prior, Cambridge. See Alumni Cantabrigienses; Metcalfe, Visitations of Essex, 1634.

(39.) John Peile, Christ's College (London: F. E. Robinson & Co., 1900), 10; Quentin Skinner, "The Generation of John Milton," in Christ's: A Cambridge College over Five Centuries, ed. D. Reynolds (London: Macmillan, 2004), 44-45.

(40.) Sarah Hutton, "Henry More (1614-1687)," in Dictionary of National Biography; C. A. Patrides, ed., The Cambridge Platonists (London: Edward Arnold, 1969), 32.

(41.) Mark Curtis, Oxford and Cambridge in Transition, 1558-1642 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1959), 236, 264. Although the most famous Cambridge magus was John Dee, who attended St. John's College, there were several other well-known Cambridge men who were involved with magic. The founder of Gonville and Caius College, Dr. John Caius (1510-73), had magical manuscripts in his library, which included instructions on how to obtain the spirit of a dying man as a familiar spirit. British Library, Add. 36674, f. 38. St. John's also produced John Vaux (c. 1604-5), who was accused of dabbling in magical practices and selling strange books from his church altar. See Alumni Cantabrigienses. John Lowes (c. 1590), the vicar of Brandeston in East Suffolk, was also educated at St. John's. He was accused of harboring witches and practicing black magic and eventually got caught up in the net of witchcraft prosecutions conducted by Matthew Hopkins in 1645. See C. L. Ewen, Witchcraft in the Star Chamber (London: n.p., 1938), 44-54. As a young man, Abraham de la Pryme (1671-1704) experimented with magic while attending St. John's. See Abraham de la Pryme, The Diary of Abraham de la Pryme, ed. Charles Jackson, vol. 54 (London: Surtees Society, 1870). The translation of Agrippa's Fourth Book of Occult Philosophy in 1655 by Robert Turner included seven dedications from members of Cambridge University, three of whom were from St. John's College. See the preface to Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa, Of Occult Philosophy, or Of Magical Ceremonies: The Fourth Book, trans. Robert Turner (London, 1655). Keith Thomas mentions several more Cambridge and Oxford University magicians who displayed interest in the occult. See Thomas, Religion and the Decline of Magic, 226-27.

(42.) Macfarlane, Diary of Ralph Josselin, xxiv, 23-24, 81.

(43.) ERO Q/SRa 2/78, Petition of constables of Stisted.

(44.) Garthine Walker, "Rereading Rape and Sexual Violence in Early Modern England," Gender and History 10 (1998): 1-25.

(45.) Perhaps relevant to our story were the exploits of John Lambe, a cunningman who was stoned and cudgeled to death by a crowd in London because of his magical practices, as well as an alleged rape. This story was widely known because it was published in a pamphlet in 1628. One of the incidents described in the pamphlet concerns Lambe causing a woman, who was walking in the street, to take up her coats above her waist. When asked by other women why she was engaging in such shameless behavior, the woman replied that she thought she was wading through a pool of water. In other words, she was under the spell of a magician and no longer had control of her actions. Therefore, she was not responsible for her actions and could salvage her honor. It also demonstrates the use of magic for deviant, sexual purposes. See A Briefe Description of the Notorious Life of Iohn Lambe, otherwise called Doctor Lambe (Amsterdam, 1628).

(46.) Elizabeth A. Foyster, Manhood in Early Modern England: Honour, Sex and Marriage (London: Longman, 1999).

(47.) According to Alexandra Shepard, Meanings of Manhood in Early Modern England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 36, 45, an elderly man's right to patriarchal privilege was dependent on his physical strength and his past reputation. Manhood had to be constantly maintained through the subordination of women and lower status men.

(48.) ERO Q/SR 110/75-79.

(49.) Robert Bucholz and Newton Key, Early Modern England 1485-1714 (Oxford: Blackwell, 2004), 240-44.

(50.) Macfarlane, Diary of Ralph Josselin, 14-15. In 1645, when Alston was pressing charges, the whole area of East Anglia was under threat from royalist forces: Purkiss, English Civil War, 386.

(51.) Our Robert Aylett (b. 1615) was the first-born son of Robert Aylett of Stisted (d. 1653) and Elizabeth Barrows (or Burroughs). Robert (the Elder) of Stisted was the second son of Robert of Coggershall (d. 1603). Robert of Coggershall was the third son of William Aylett of Rivenhall (d. 1583). The second-born son of William was Leonard of Rivenhall, who was the father of Dr. Robert Aylett. Therefore, our Robert's great-grandfather was Dr. Robert Aylett's grandfather. See Matthew Steggle, "Robert Aylett (c. 1582-1655)," in Dictionary of National Biography; Alumni Cantabrigienses; Metcalfe, Visitations of Essex, 1634; Morant, History and Antiquities of the County of Essex, 2:393; Frederick M. Padelford, "Robert Aylett," The Huntington Library Bulletin 10 (Oct. 1936): 36-41; J. H. Round, "Robert Aylett and Richard Argall," The English Historical Review 38 (1923): 423-24.

(52.) Macfarlane, Diary of Ralph Josselin, 31.

(53.) Stuart Clark, Thinking with Demons: The Idea of Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 532-34. Keith Thomas argues that Catholics were just one of many scapegoats accused of magic and sorcery, although this claim has since been debated: Thomas, Religion and the Decline of Magic, 559-60.

(54.) Keith Thomas notes that by the time of the Elizabethan Reformation, recusant priests were often deemed conjurers: Thomas, Religion and the Decline of Magic, 68.

(55.) Roper, Oedipus and the Devil, 43.

(56.) Harold A. Goolishian and Harlene Anderson, "Narrative and Self: Postmodern Dilemmas for Psychotherapy," in New Paradigms, Culture and Subjectivity, ed. D. F. Schnitman (Cresskill, N.J.: Hampton Press, 2002), 218-21.

(57.) Stephen Wilson, The Magical Universe: Everyday Ritual and Magic in Pre-Modern Europe (London: Hambledon and London, 2000), 441.

http://0-find.galegroup.com.library.vu.edu.au/itx/infomark.do?&contentSet=IAC-Documents&type=retrieve&tabID=T002&prodId=EAIM&docId=A171889290&source=gale&srcprod=EAIM&userGroupName=vut_main&version=1.0>.

Gale Document Number:A171889290

A John Alston of Widdington held copyhold 164? see [7101]

Stisted Register - Burial Thurten day of Sept 1656 Mr John Allstone

20 Sep 1658 Mr John Alston was buried from Milles

At the Essex Record Office in Chelmsford

DEEDS

Level:

item Reference Code D/DGd/T6I Dates of Creation 1615-1768 Extent 67 Scope and Content Deeds of mansion on house called Cusee Hall, with dove- house, barns, stables, yards, orchards, gardens and land (85a.) [field-names], 1615-1707; deeds, 1641-1700, including messmate called Colemans with land (43a) [field-names]; manor house called Hosyes alias Houses, with buildings, yards, gardens, orchards and land (157a.) (field-names), 1617-1709; deed, 1676, including cottage with windmill, stable, yards, gardens and ground (1a); messuage called Crophall, with outhouses, yards, gardens, backsides and land (3a.) abg. on King's highway from Cusshall to parish church, Toppesfield, 1684-1707; land (42a.) [field-names] copyhold of Manor of Barwicks and Sootneys, 1678-1703; and 3 pieces of land (4a.) copyhold of manor of Stoke- juxta-clare, 1706-1722 encl. valuation, 1768, of farms called Abbots and Gurtens in Haverhill; near contemporary copy of Probate copy, 1586, of will, 1586, of William Bigge of Toppesfield, yen.; and attested copy, 17th cent, of attested copy [n.d.] of will, 1653, of John Alston of Stisted, gent.

Date From 1615 Date To 1768

Ref: Susan Perrett.

12.2.2007 - Chelmsford R.O.

Parish of Stisted - Fiche d/P 49/1/1 and 49/1/2 for C.M.B for 1638-1689, much in Latin or damaged and very hard to read, the originals are needed with use of more magnification.

Susan Perrett.

Other Records Other Records

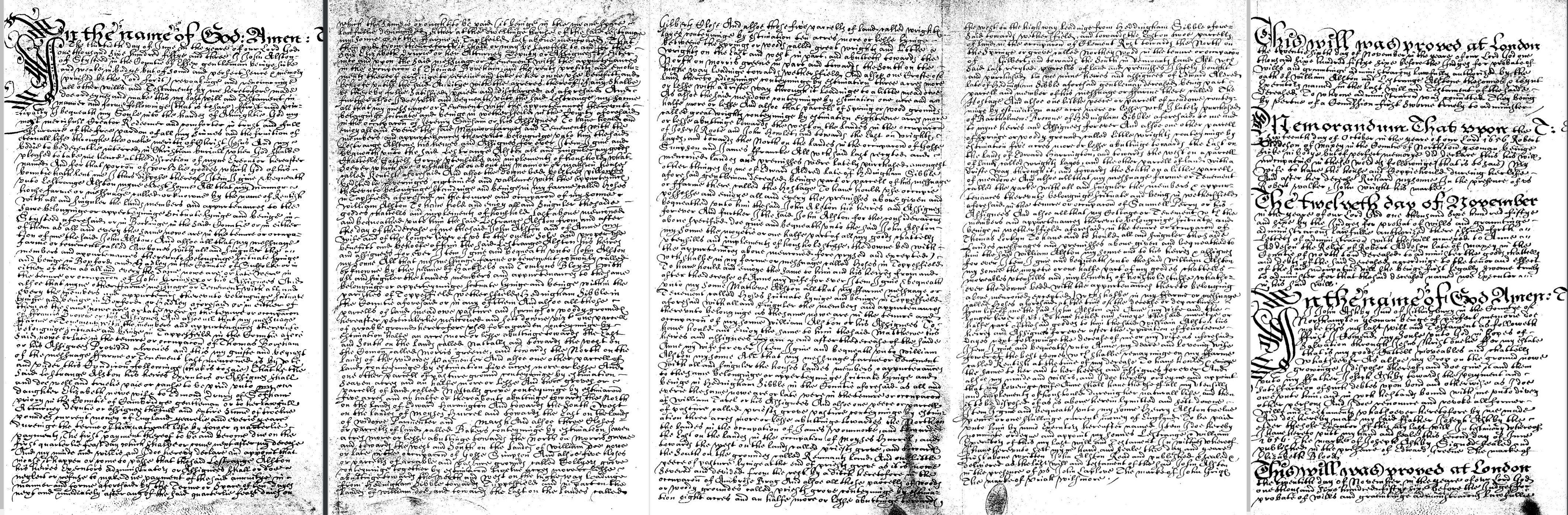

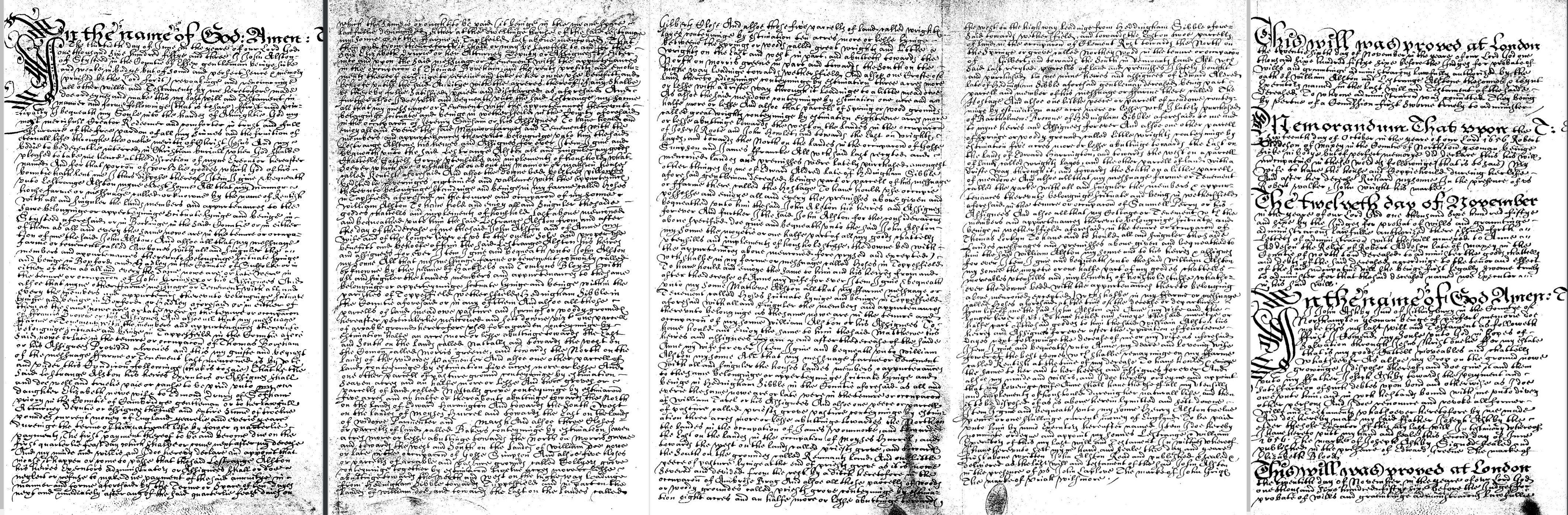

1. John Alston: Origional Will - PROB/11/260, 30 Jun 1653, Stysted ESS.

Extracts below

2. John Alston: Will - Extracts, 30 Jun 1653, Stysted ESS.

WILL OF JOHN ALSTON OF STISTED, Co. Essex, Gent.

Dated 30th June 1653.

I give to L'estrange Alston my eldest son my manor house farm or messuage called Kentish, in Stisted or in Bocking, now in my occupation - also my messuage caalled Awbones in in Boxford and Hadley co Suffolk another farm in Boxford or Hadley also my messuage lying in Tappesfield, Co. Essex provided he pay to my daughter Elizabeth, wife of Edmond Drury of Sofham Priory, Cambridge, gent. an annuity of L12.