Percy Ashton ELWORTHY [544]

- Born: 27 Mar 1881, Timaru South Canterbury NZ

- Marriage (1): Bertha Victoria JULIUS [542] on 1 Oct 1908

- Died: 10 Jul 1961, Ringstead Havelock North N Z aged 80

Another name for Percy was Willie. Another name for Percy was Willie.

General Notes: General Notes:

Elworthy Percy Ashton.

May 1894-1899. House Andrews. Son of Edward Elworthy, Pareora, Prefect; XV 1899; WWI Capt 1st Life Guards; Knight Order of St John; Rwg Blue (Cantab). Farmer. Havelock Nth, died 10 Jul 1961.

Christ's College School List 1850 - 1965

Elworthy Percy Ashton. Adm. at Trinity Hall, 1900. S. of Edward, Esq. of Pareora, Timaru, New Zealand. School, Christ's College, New Zealand. Matric Michaelmas 1900. Return to New Zealand at the end of his 2nd year. Served in the great War, 1914-19 (Lt. Life Guards)

Alumni Cantabrigienses.

Elworthy, Percy Ashton.

Sheep Farmer. "Gordon's Valley" Station, Timaru, NZ Born Timaru NZ 27Mar. 1881. Son of Edward and Sara (nee Sharrock) Elworthy of Wellington, Somerset. Run holder of "Holme Station" Timaru. Educated: Christ College, Christchurch, and at Trinity Hall, Cambridge. Rowed in winning crews, Clinker Fours at Cambridge and Thames Cup Henley 1902. In 1902 took over "Gordon's Valley" a portion of the original "Holme Station" taken up by his father in 1863 on which he built his present house and other buildings. In 1907 he went on an expedition to Portuguese S. Africa with Mr Carlisle Studholme of Waimate (shooting and game hunting). During the Great War he served with the First Life Guards in France, 1915-18, being promoted to the rank of Captain. Married: Bertha Victoria, youngest daughter of His Grace Archbishop Julius, 1st of October, 1908. Issue: 2 sons and 3 daughters. Janet Mildred, born 1909 died in London 1919; Samuel Charles, educated at Marlborough College, Wiltshire, and Trinity College Cambridge; Anthony Churchill, educated Marlborough College Wiltshire and in France; Mary Antoinette, educated Brondesbury Manor House, London, and in Paris; and Alice Diana aged 11 years. Clubs: (London) Bath, Leander, RAC Clubs: (NZ), Timaru and Christchurch. Creed: C of E. Home address: "Gordon's Valley" Timaru, NZ.

New Zealand, Who's Who in New Zealand and the Western Pacific, 1908, 1925, 1938 - Ancestry

Percy (Willie to his family) was adventurous and fun loving, never one to feel self-conscious about having been born with a silver spoon in his mouth, he lived a happy and full life. He is remembered by his daughter Di as a gentle and loving father, with a great sense of humour. He was educated at Cathedral School "and hated it" Christs College, Christchurch, where in his own words "I did as little work is possible, broke every school rule and was beaten without ceasing in consequence" and Trinity Hall Cambridge, England, where he was a popular figure. He rowed for Trinity Hall, but did not stay the required three years so went down without a degree. A fine sportsman Percy was a climber, horseman, polo player, he co' founded the Timaru Squash Club, and hunter. From 1902 he farmed Gordons Valley, his share of the old Pareora block, split up in 1910. He was not a hands on farmer, and Gordons Valley was run by managers. He and Bertha retired to Ringstead Havelock Nth N.Z. about 1951.

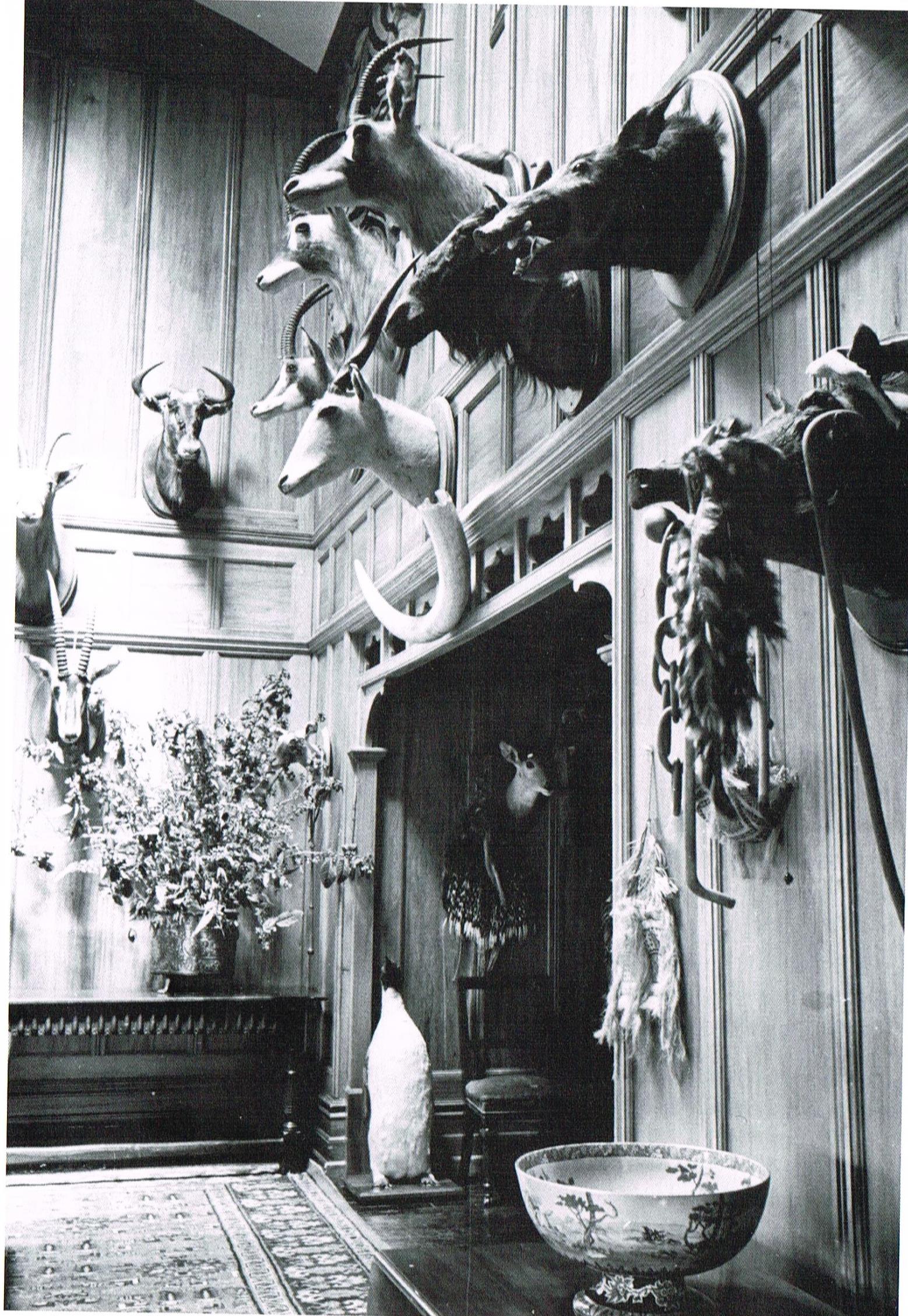

The old homestead at Gordons Valley was set in a magnificent parkland of exotic trees planted by Percy, and contained numerous trophies from his safari to East Africa in 1906. He served in France during WW1 with the First Life Guards, with the rank of Captain, his fine horsemanship stood him in good stead. However from the time he was demobbed he rejected the honorific, deriding those that clung to wartime rank. Percy was a Knight of the Order of St John.

Very interested in motoring, he bought his first car, a Simms Welbeck in Christchurch in 1902, taking 20 hours to travel back to Timaru in it. In his splendid memoir in Edwards Legacy, Percy noted "Bertha and I have owned a great variety of cars in our lives, from model T. Ford's to Hispano Suizas, Stutz, Rolls Royce, Jaguars, Riley's etc., and now we are back to Fords. Always at the vanguard, Percy, in the first decade of the 20th century drove all over New Zealand, much of it on unformed roads, his was the first car to enter Queenstown, to the consternation of the locals, and the first to cross the Crown Range, a restricted road even in 2012. He and Bertha first flew in 1915 from Hendon London with Graham-White, they hoped to fly to Scotland, but ran into a dense fog over Norfolk, landing at Kings Lynn they had lunch, taking off again the engine failed and they crash landed, unhurt, on the Fens. Soon after, back in New Zealand, he and Bertha hired a plane to fly to Dunedin for a meeting, there being no airport they had to land on the beach, which they did, bursting both tires. The wind had got up by the time they wished to return and the takeoff was almost unsuccessful.

Percy was a generous man, the researcher Edward Fenn enjoyed fascinating visits to Gordons Valley as a youth, and was given a Westley Richards .303 hunting rifle by Percy, which he still treasures (1999). Percy was aged 80 at his death.

His grandson Dermot writes of him in 2014 from his book: "It was after having come down from Cambridge and whilst staying at one of his London clubs that Willie (Percy) decided to visit the zoo in Regent's Park. The offering to a gorilla of a bag of peanuts skewered on the end of his umbrella began a story he often told me when I was little. The gorilla, no doubt bored half to death with peanuts, tossed the bag aside and grabbed the umbrella. After a lengthy tussle - the creature nonchalantly leaning against the bars and single-handedly toying with this new trinket, Willie, red-faced with effort and determination to retain his property - the brolly disintegrated with Willie shooting backwards, sprawling on the ground. The gorilla carefully examined the remnants of the stricken parapluie and thinking the prize hardly worth what little effort he had expended upon its capture, threw the broken pieces back at Willie."

Percy is believed to have paid for a Spitfire named "Rainscombe" as a contribution to the war effort. (Percy owned Rainscombe House Oare Wiltshire) His Grandson Dermot continues (2014) to seek confirmation of this but the trail has gone very cold. He comments "it would be wholly in character for Willie to make such a gesture and say nothing about it".

Percy also owned another country house in England known as Forbury. Dermot Elworthy in 2018 opines that it existed in a locality known as Crossways the intersection of Forbury Lane, Pebble Hill & Kintbury Road, Kintbury, Hungerford, Berkshire

RG17 9SU. The house no longer appears to exist, it may have fallen victim to the Labour Government's savage attack on wealth in Britain after WWII.

After studying family pictures of Forbury Dermot considers his proposition, above, to be unlikely - 2019

Grandson Dermot remembers a school function for St Johns Ambulance volunteers, where Willie who lived nearby did the honours: "Certificates were awarded at the end of term ceremony in Big School (Hereworth Prep Havelock North) and all those who didn't manage to kill anyone in the course of instruction received a splendid fake parchment. These were presented by an imposing man of military bearing, more than a little intimidating in the full ceremonial regalia of a Knight of the Sovereign Military and Hospitaller Order of St John of Jerusalem, of Rhodes and of Malta. My turn came; with knees a-trembling and stomach churning, I was presented to this vastly imposing personage who must have arrived from Olympus at the very least. "Willie, it's you!" I exclaimed. To me, Willie was a god and he never gave me any reason to suspect even so much as a toe of clay".

OBITUARY: PERCY ASHTON ELWORTHY.

Percy Elworthy- prominent in farming and sporting circles in South Canterbury for many years - died at his home, " Ringstead," Havelock North, early yesterday morning. He celebrated his eightieth birthday last March. The sixth son of Mr Edward Elworthy, of Holme Station, he was educated at Christs College (Christchurch) and Trinity Hall (Cambridge). Returning to New Zealand in 1902, he took up Gordons Valley Station, which he continued to develop until about 10 years ago when he moved to "Ringstead."

At Cambridge, Mr Elworthy rowed for his college," and he had the distinction of gaining selection in crews of the famous Leander Club. While at university he spent much time climbing in Switzerland and France and made ascents of many of the major peaks in the Alps, including some first traverses. Mr and Mrs Elworthy and their family lived for many years in England, and all their children were educated there. A keen horseman, Mr Elworthy won many steeplechases and point-to-point events and, with his brothers Arthur and Herbert, he held the hunting contract for the South Canterbury Hunt for some years during a difficult period in the early 1900's.

Mr Elworthy excelled in polo, too, and with his brothers, and the Orbells competed throughout the country with success. Big-game hunting had its fascination and trophies at Gordon's Valley Station today still attest the success of a trip which he made to Portuguese East Africa in 1906 with Mr Carlisle Studholme, of Waimate. When there was a movement in 1933 to form a squash rackets club in Timaru, Mr Elworthy was one of four men who among them provided the L1000 required for the purchase of land in Brunswick Street and the erection of a court.

The automobile always held a fascination for Mr Elworthy and he became the first man to drive over the Crown Range by car. Mr O. A. Gillespie records another motoring feat in his book "South Canterbury, a Record of Settlement." "Today, when people drive gaily from Timaru to Christchurch in a few hours, the record of P. A. Elworthy's first drive in 1902 is a comment on half a century of change. He left Christchurch at 6 o'clock one morning in a single-seater (Family photos show the car to be a four seater) Simms Welbeck car he had just bought and, in order not to wake his family, climbed through the scullery window at Holme Station at 2 o'clock the following morning, after a 20-hour journey."

In the First World War, Mr Elworthy served with the First Life Guards in France, rising to the rank of captain.

The work of the St John Ambulance occupied many hours of Mr, Elworthy's attention and he became a Knight of the Order of St. John. After the Second World War he presented the chassis of an ambulance to the Timaru Association,

In 1908 Mr Elworthy married Miss Bertha Julius, youngest daughter of Archbishop Julius. He is survived by his wife, two sons and two daughters. His elder son, Air Marshal Sir Charles Elworthy, is Commander-in-Chief of the British Forces in the Middle East and is at present organising the British military operations in Kuwait. The second son, Mr Anthony C. Elworthy, is New Zealand manager for a United Kingdom engineering firm. The elder daughter, Anne (Mrs Shaun Jaffres), lives in Madras, and the younger daughter, Diana (Mrs J. C. Wilson) lives at Bulls.

Research Notes: Research Notes:

Percy Ashton Elworthy had a wonderful life and was loved by all who knew him.

Who best but he to tell us of it.

A Memoir by Percy Elworthy

Of my father, so much has been written and is available to my children that I need not say much, except that he was a most wonderful father to me and that I and my descendants can never be grateful enough for the heritage that he left us, both in property and also in example of his life and upright character. My great regret is that he did not live long enough to help me through my young manhood. Of my mother I cannot speak too highly - she was loved by all, not only by those of her immediate circle; old Pareora was renowned for its hospitality. When I was a boy my home was open house to all travellers from England and other parts of the world and, although a very large house, was generally full to over-flowing with guests who did not come for weekends but for weeks on end. There were no staff difficulties, so entertaining was easy.

I was born in Timaru in a house on Le Cren's Terrace, where my mother had gone for her confinement, on March 27th 1881. My mother had returned from England only two weeks previously where she and my Father had spent two years, so that even if I was not born at Home, I was conceived there; a thought which I find very satisfactory. Of my early childhood I remember very little. We were a family of eleven children, four of whom died in early years. Those who survived were Maude (Jameson), Edith, Arthur, Ethel (Bond), Herbert, myself and Muriel (Williamson). At the age of six I was taken to England where we remained for two years. Arthur worked with a tutor - he was delicate and did not go to school except for a few terms to Baker's School on Banks Peninsula on our return to NZ - and was mostly educated by tutors. Herbert went to Elstree Preparatory School where, with Winston Churchill, he sat at the bottom of his class.

During the time that we were in England, my father returned to NZ in the old Ionic. Before reaching NZ, the ship's crankshaft broke and she drifted, helpless, towards the Antarctic. The Captain told the men on board that there was little hope of the ship being saved. However, a wind sprang up from the south, all sails were set and the ship was carried almost as far as Dunedin where she was taken in tow. In the meantime, my mother in England, believing that the ship had been lost and my father dead, put us all into mourning, as was the custom in those days. Eventually, she received a cable telling her that he was safe.

On our return to NZ, I was sent at the age of eight to the Cathedral School in Christchurch, then a preparatory school for Christ's College, although now it is quite separate. As I pass along Park Terrace, I often look up at the window of the room where I got my first caning from Merton, the Headmaster, and many subsequent ones. As instructed by my mother, I took a hansom cab from the Christchurch railway station. Her final gift to me was a case of apples. With my trunk on the top, as we went along at a walk, I could hear the cabby prising open the case. There were not many apples at the end of the journey and he must have found some place to put those that he didn't eat. I was far too frightened to say anything. I was at that school for four years and hated it.

Then I went on to Christ's College and was in Worthy's House where School House now stands. Bourne was headmaster at that time, lately arrived from England and a very poor specimen. I was not a pattern boy by any means. I did as little work as possible, broke every school rule and was beaten without ceasing in consequence. The old house was dilapidated and often, at night, the bigger boys would violently shake the walls and then, rushing out, would shout "Earthquake!", which was a signal for all the smaller boys to rush out. Our house was connected with one of which Andrews was housemaster, he usually was known as "Cocky Bill". He owned a fine Persian cat of which he was very proud; this cat used to curl up on our beds. One day we caught it, clipped it like a French poodle and then pushed it through into Andrews' side of the house. He was so mad that he drowned the poor animal.

We had a French master whom we called "Jo Jo". Like all foreigners, he could not control his class and we gave him a really awful time, although we really liked him. One day, knowing that I was in for a hiding, I padded myself with cardboard, caps, etc., to such an obvious extent that even Jo-Jo noticed it and when I bent over he said, "Un-ship yourself, Mon" to the joy of the whole class. Another master, Duckfield, suffered even more when he took prep. On the evenings when there was a fire, Red Neill and I would make bombs and, as soon as there was a chance, would throw one onto the fire. In the smoke and confusion, ashes flying everywhere, Duckfield would rush madly round with his cane, hitting anyone who came in his way. Sometimes someone would blow down the gas pipe, when all the lights would go out. Naturally there were no water closets or drainage of any sort in those days. The Christ's College latrines were placed at the back of where the new open air class rooms are now. The buckets were emptied at night into a night-cart - a big open dray tank that was hauled by a horse which had a bell attached to his pole. In Worthy's house one night we placed candles in the "jerries" and when we heard the night-cart, we lined the windows with our "searchlights". The horse was so startled that he bolted, a wheel hitting the kerb and the contents were spilled over the quad!

I never cared for cricket but played rugby and was in the first fifteen for two years. I was a strong swimmer and believe that I still hold the record for under-water swimming. I won the Swimming Championship in 1898. I do not look back at my time at Christ's College with any pleasure, although I have a lasting regard and respect for some of the masters, Jock Collins in particular. Also "Fatty" Flower and Parson Hare, but I made up my mind that, if I had any sons, I would educate them in England and this, I am glad to say, I was able to do. While I was still at College my father died suddenly of a heart attack at the early age of 62. A very great loss to his family and to the whole community, especially to my mother who was very dependent on him.

In 1899 my elder brother Arthur and Ella Julius were married in the Christchurch Cathedral and later went to live in the old Pareora home which my mother vacated when she and Edith bought a very nice property on the Papanui Road in Christchurch. In the same year my mother, Herbert, Muriel and I went home, travelling with us were Githa Williams, (one of the T.C. Williams) and Sir Wyndham Anstruther. We travelled in the old Mariposa via Apia to San Francisco, picking up copra at Pago Pago. After some days at sea the copra caught alight. Later, thinking that the fire was out, they lifted the forward hatch, hastily replacing it when billows of smoke poured out. They tried to put the fire out by steam but the hoses burst. Finally, the crew and passengers managed to control it by a chain of buckets until we reached the port where it was found that the cargo was entirely gutted.

We all went down to Los Angeles, then only a small town which Bertha and I have visited twice since - in 1928 and again four years ago. On my first visit we went to Santa Catalina where I spent some time tuna fishing from boats and to Williams on the Santa Fe Railway. From there we drove buggies and express wagons to the Grand Canyon and camped at its edge. While we were there we rode to the bottom of the Canyon on mules; only a very rough track existed but the mules were surefooted. Muriel and Githa were among the first women to ride down to the Colorado River. In 1954, fifty-five years later, Bertha and I travelled by air over the same spot. The news that I had visited the Canyon so long ago had reached the local papers and, as a result, we had to submit to having our photo-graphs taken both at the Los Angeles and the Chicago airports where I was questioned by reporters about the Canyon in the early days.

To return to 1899: my father's cousin, Arnold Wallis, brother of Frederic Wallis, Bishop of Wellington, was a don at Pembroke, Cambridge. He put me down for Trinity Hall, at that time high on the river and, after passing my "Little Go", I joined the college. I admit that my chief interest was sport and, owing to a certain ability in that line, I was welcomed and allowed to stay on in spite of my lack of book learning, a thing which would never be tolerated now. The first year I rode for Cambridge in the Cottenham Steeplechase - Cambridge v. Oxford. My horse fell at the last fence and I was badly concussed, losing my memory for a considerable time and later, I was sent to Capri to convalesce. I took up rowing with great enthusiasm; I had done no rowing at Christ's College which I believe was a great advantage as I did not get into a bad style as did some others who had rowed at their public schools. I rowed bow in my College's First Boat. Trinity Hall was second on the River. In 1902 at Henley, we won the Thames Cup and in the same year Trinity Hall Clinker Fours, in which boat I rowed three and won the Intercollegiate. I was urged to remain on at Cambridge for my third year in order to get my Blues which had been promised to me, but my brother Arthur was demanding my return to New Zealand to take over the property left to me by my father, and I was compelled to turn the invitation down.

During the long vacations while I was at Cambridge, I used to climb in Switzerland. Each year, I engaged the same wonderful guides, Allois Pollinger and Lockmatter. We made the main ascents, including the third ascent of the Weishorn, 14, 804 ft. We traversed Mont Blanc, 15,781 ft. then, via the Mer de Glas to Chatillion on the Italian side, and on from there to Aosta where we cut over a pass of the Matterhorn to Zermatt. We climbed the Matterhorn, the Dent Blanche and Monta Rosa. From Interlaken we climbed the Monch and the Eiger. The two guides were very anxious to come to New Zealand to climb and offered their services free for a season if I would pay their passages out. It would have been wonderful but I realised that I must get down to work on my return. I have done no climbing in New Zealand. Bertha has just put on a long- playing record which, she tells me, is Chopin's B flat Piano Sonata. In this I recognise the Funeral March which holds many memories for me.

When I was at the University, I joined the Cambridge Mounted Infantry. In 1901, at the expressed wish of the old Queen before she died, Cambridge and Oxford territorials (Bug Shooters), lined the route inside Windsor castle walls at her funeral. In spite of reversed arms and lowered head, I managed to see quite a lot of what was going on. At the bottom of Windsor Hill, the horses pulling the gun carriage and heavily-laden coffin, jibbed and their places were promptly taken by a hundred Bluejackets who hauled it to the top. I was stationed just near the entrance to the Castle and all the crowned heads of Europe passed within a few feet of me including the Kaiser, who walked with King Edward 7th and one could almost feel their intense dislike of each other. Except for a pie eaten in the early morning, we had no food throughout the many hours that we were on duty and many men fainted. During my last term at Cambridge, the Colonel of the 6th Dragoon Guards (Carabiniers), Colonel Sprot, came up to Cambridge to see me. My cousin, Charles Elworthy, known in the Regiment as Ruby because of his hair, had been killed in the South African War and their Regiment wishing to retain an `Elworthy', the Colonel had come to ask me to join it. I was sorely tempted, eventually tossing a coin as to whether I would be a soldier or a farmer, and my fate was decided. I have felt rather divided between the two professions ever since but do not think that I would have cared to be a "peace time" soldier.

I returned to NZ in 1902. My brother Herbert and I lived in the old Pareora Cottage with the Manager, Mr. Cartwright. Part of this cottage, which still stands, was moved to its present site many years before from Gordons Valley where, originally, it was the home of George Gordon after whom the valley was named. Gordon came to this country in 1859 and was employed by Messrs. Harris and Innes, the first owners of the Pareora Station, as a boundary rider. I have had a block of limestone placed recently on the actual site of his hut, in the bush above the present farm buildings. The hut was made of pit sawn Totara slabs and was thatched with cabbage tree leaves. Some of the original apple trees remain and there are traces of the old stables as well as many descendants of his goose-berry bushes in the "bush".

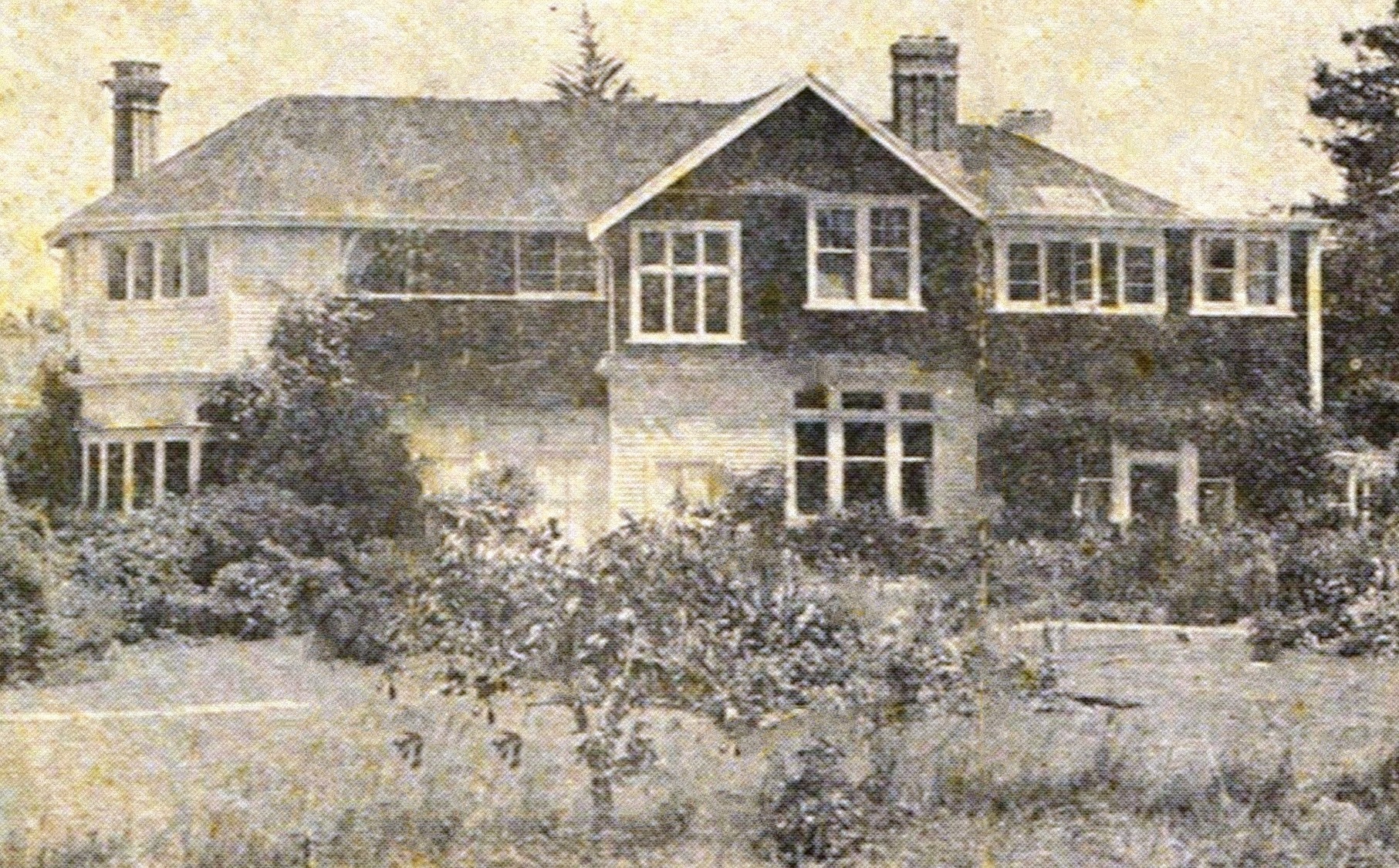

After about two years, Herbert and I decided to build on our own properties - Craigmore and Gordons Valley. I built a large bungalow in an open tussock field using the best timber - heart of Totara and Rimu. During the first winter I planted acres of English and shelter trees, the latter gradually having been cut down as being no longer useful and the former having been a joy for many years. The farm buildings were put on the flat, well away from the house. My first employee was Tom Ward, for whom I built a cottage at the entrance to our drive. This recently has been cut in half and moved down to the farm buildings to make an extra farm cottage; it is occupied by the shepherd. Tom and I did our best to look after 14,000 acres - my portion under my father's will. Contractors did all the ploughing and fencing. For eighteen months after settling into my own home, my old Christ's College friend, Pat Lindsay, lived with me; we were looked after by an excellent housekeeper and in those days a housekeeper really knew her job. Water was my chief problem. There was plenty of it but it was very hard, as was only natural in limestone country. During those years I installed a variety of softeners, none of which proved satisfactory and the pipes and kettles etc. quickly corroded and needed frequent renewal. Within the last few years, this trouble has been overcome. The main pipe of the Downloads water supply crosses the hill opposite the house and I obtained permission to use the water.

In 1909 I added a top storey to the house and now find it far too large for our needs in spite of having taken down large portions of it from time to time. It has been a wonderful home for us and our children and grandchildren and we always enjoy a few weeks in it from time to time since we went to live in Hawke's Bay, living in a corner of it and always finding it in spotless condition, thanks to Barbara and Robin [Johnston] who keep it spotless and well aired as did Mrs. Johnston Sen. when she was here. We owe a great deal of our comfort and happiness in our old home to the Johnston family.

In 1907 I went to South Africa with Carlisle Studholme. We landed in Durban and made our way to Pietersburg in the Northern Transvaal, from where we trekked with mules and wagons. Two Boers and eight natives accompanied us. We reached the Limpopo River and this we had difficulty crossing, it being a mile wide and having banks twelve and four-teen feet high. It took us a week to make the crossing, the natives cutting tracks down the bank for the wagons. When shooting crocodile in the back water of the river where the country was covered with forest, I saw many crocodiles with their noses sticking out of the water. Noticing what I took to be a large one, I fired. Instantly there was a commotion in the water and it turned out that I had shot a python which had been bathing. Its back was broken and as it was helpless the crocodiles attacked it. The natives with long branches managed to get the tail out of the water but the crocodiles got the rest. The natives would often go into a river or pan without fear or harm from crocodiles but only after consulting the bones of different small animals which they carried in snakeskin bags around their necks. These they would spread out on the ground after smoothing it down and shaking the bags and, by their position, would know whether the crocodiles would bite that day. I never knew it to fail.

One day, after a long trek, I threw my valise from the wagon under a Mapani tree and prepared to spend the night there. I noticed that the leaves and the dried grass were moving slightly up and down and drew the attention of one of the Boers. He got a heavy stick, brought it down and out stretched a python -its back was broken. Native women did all the work in the kraals; when they were too old to work, they were led out into the forest and left under a tree with water and food which was renewed each day. Eventually they were taken by some animal, lion or panther, etc. One day we came on one of these old women when we were searching for water. She seemed to be perfectly happy and after directing us, she returned to crooning over her little idols which she had with her.

It was a great help to us that one of the Boers could make himself understood by most of the tribes which we came across. We caught animals as well as shooting them and the latter was necessary to a great extent to provide food for our own and the wild natives. The latter we paid for any work that they did for us and the mealies which they supplied by giving them biltong. We had, also, beads and brightly-coloured materials which we had brought with us for them.

One day we shot a lion and upon going out the following day to skin it, we saw two cubs run out. We caught one, tied it with a rimpe (leather thong) to a tree and then climbed into the tree hoping that its outcry would attract the mother. As she did not come, we sent a native to the wagons to bring a cape cart and, after feeding the cub on liver and condensed milk, we put it in a box and took it back to the wagons and, at the very end of our trip, we gave it to the Pretoria Zoo. We became very fond of the cub and it was docile with us but would not allow any native near it.

Early one day we came on elephant spoor. Following it all day we came to a place where we could hear the elephant's guts rumbling - a noise like distant thunder. Suddenly they got our wind and went crashing through the forest and were away, a fair-sized bull taking up the rear. I jumped from my horse and shot him from behind, and, following up, my next shot killed him. I killed this elephant illegally as I held no elephant licence. We covered the carcass, after removing the tusks, with earth and branches so that the vultures would not see it and thus draw attention to the kill. They would have reported it to the native police. Our method of getting into the country where we wanted to be was for one of the Boers, Studholme and I, to ride on ahead of the wagons and pick our route by blazing the trees. The wild natives would then clear a track with the axes which we had with us, our head man keeping a tally and making payment for the work with biltong. We would ride ahead on mules looking for water - an essential for the mules as well as the humans. We had hoped to have used the same track coming out again but the elephants, who resented our presence, had pulled down trees across the tracks and covered these with still more trees so that we had to cut another route.

One is often tempted to follow the honey bird and many hunters have been lost in the forest through him. This little bird, by twittering and flying around, attracts attention and then leads him from tree to tree, finally arriving where bees have made a hive in some rotten stump. The bird hopes to get a picking when the honey is taken, but by this time the hunter is lost and cannot tell his direction because the sun is obscured by the trees. We came on many baboons who live in the rocky kopjes. When alarmed, the female does a bolt, the baby sitting on its mother's back facing the enemy behind, hanging on to its mother's upright tail and shouting defiance. The old man baboon brings up the rear showing great fight and baring his teeth, but generally he loses his nerve and hurries after his harem. Baboons when in force have been known to stone hunters to death.

As one walks through the forest the monkeys overhead, thousands of them, keep up an incessant chatter and one can see little faces peering down at one, their fingers parting the leaves and sending down a consistent bombardment of little twigs. Studholme dislocated his knee and had to lie up in the wagon for about two months but from there, managed to get quite a lot of shooting. One day the Boers and I set off to shoot hippopotami. We reached a big pan which obviously had been the spot where many had been wallowing recently. We camped near it. We saw where natives had been setting traps over the tracks of the hippopotami, leading to the water. Their method was to bend over a tree from which was suspended a vine rope with a poisoned dart and a weight at the end. A trip rope was put across the path and when touched this would release the dart which would penetrate the skin to a considerable distance. The wounded beast would then make for water and die. When the putrefying carcass came to the surface, the natives would contrive to get it out and use it for food, leather, etc. We had to evacuate this spot as the mosquitoes made life impossible and we had no nets. We caught many zebra and took some back to Pietersburg Zoo and sold others to Hagenbeck, the man who bought animals for zoos all over the world.

To my mind the most dangerous animal in Africa is the bush pig. It hunts in packs of some two or three hundred and has a nose far better than any fox hound, even when the scent is two or three days old. These packs will pursue a hunter on horseback for days until his horse is exhausted and the man has to climb into a tree, taking his rifle with him. He may shoot a dozen or more; these are eaten by their companions who will wait indefinitely for the man, staying around the foot of the tree knowing that, in time, he will fall out of it. After we had been in Portuguese East Africa for four months, we made preparations to come out. After re-crossing the Limpopo River, we left the wagons and Carlisle Studholme and I went on ahead, taking a native boy with us and travelling in the cape cart as I was having repeated bouts of malaria fever. Eventually, I became so ill that "Kooti" (C.S.) decided to leave me and go and try and get some medicine. I was left in charge of the native boy, my valise under a tree. He kept me supplied with water but spent his nights up the tree for fear of wild beasts. Studholme returned in three days bringing medicine from a Portuguese outpost hospital and when I was stronger, we set off again, reaching the hospital in a couple of days. I had a temperature of 104, was put into a cold bath and in time got rid of the dirt and lice with which I was covered. For some days I was dead to the world but later was well enough to go on to Pietersburg where I went to hospital again. Studholme went on to Durban where I joined him eventually. Later he returned to New Zealand. I went from Africa to England (1907) in the hopes of becoming engaged to Bertha who, with her sister Ada, was at home on a visit.

Later in the same year I followed her out to NZ. We became engaged and were married in the Christchurch Cathedral on October 1st 1908. The best day's work I ever did and I can look back on fifty-one years of great happiness. It is said that opposites make the best mates. We have proved it. Bertha has never been keen on sport, was wrapped up in music and books etc. I was entirely of the sporting type but both of us have helped the other to develop his or her interests and they have never clashed. Over the years we find that we think of the same things at the same moment without any speech. We were married by Archdeacon Harper; Bishop Wallis who had married all Bertha's sisters, being in England that year. A full choir and a most beautiful service. Archbishop Julius, then Bishop, gave Bertha away. Ada Katherine Julius (Gray) and Muriel O'Bryen Hodge (Macdonald) were the bridesmaids with Rachel and Betty Elworthy as flower girls. Carlisle Studholme was best man and Pat Lindsay, groomsman. Eight hundred guests were invited to the wedding, the reception being held at Bishopscourt. On our honeymoon we took our car (a 35hp Talbot; something rather grand in those days) to Wellington and started our adventurous journey to Auckland. The Rimutakas were bad enough with huge boulders blocking the road in places which was shocking in any case, but they were nothing to what came later. We stayed for some days in Hawke's Bay and received much kindness and hospitality. One dinner we remember very vividly and that was at Frimley, which was in its heyday in 1908. Muriel and Sydney Williamson whose home was near Gisborne, had taken a house at Havelock North for a few months. Little did we think that we would ever make our home in that village. Our real troubles started when we left Napier for Taupo. The road was completely unmade, no rivers were bridged except the Mohaka. Punga were thrown into the worst ones to give some kind of grip but cars, naturally, were uncatered for and we had ropes on the wheels for most of the journey. We took about three days to reach Taupo, but after there the going was easier. We reached Auckland with our front wheels at an angle of 45 degrees. When in Auckland, I bought a wonderful hunter-steeplechaser, Liberty, whom I learnt to love and who produced an unbroken record in the show ring and in steeplechases, being unplaced only once. Eight firsts, five seconds, one third and later he came third in the Grand National. Liberty was so quiet that our children, when very young, used to ride him.

On November 2nd 1909 our Janet Mildred was born at Gordons Valley. We have the most wonderful memories of her; of her sunny, unselfish character, her gentleness and great love for us and for her brothers and sister. At the age of nine she died in London following appendicitis and peritonitis after a very short illness. A very great grief to us and to the many who knew her. Nurse Jensen, a Dane, came to us as children's nurse about 1911. She gave the children devoted care and love for fourteen years. Later, when they went to school in England, she left us and after staying in NZ for a short time, joined her sisters in the USA where she died.

My brothers and I ran the South Canterbury Hounds for several years, during which time I rode many of our joint horses and those of my own in steeplechases and point-to-points. I have owned some excellent horses but Liberty of whom I have written was the best of them all. When increasing weight ended my days as a jockey, I continued to race horses; steeplechasers and hurdlers, but never managed to take very much interest in them, realising that one was entirely in the hands of one's trainer and jockey. Since the First World War I have taken little interest in racing.

One steeplechase I remember vividly. I was riding an Elworthy horse called Albury in the Albury Steeplechase. All the horses were scratched except for mine and Sir James, owned by Mr Rutherford of Albury Station. It transpired that Mr Rutherford had promised the jockey half the stake if he beat me. The jockey at each fence tried to tip me and coming up the straight did his best to force me over the rails. I managed to win and he was disqualified for two years.

I have always been keen on cars. My first experience with them was in England in 1901 with Montague Graham-White, a pioneer in motoring. In 1902 I bought a Simms Welbeck from Rangers in Christchurch - a real "prehistoric peep". I drove it down to Pareora with Herbert. We left Christchurch at 6 a.m. reaching Pareora at 2 a.m. the following morning. Apart from the snail-like progress, the roads were awful, the water courses and creeks unbridged and we had a major breakdown at Geraldine where the local blacksmith came to our rescue. It seemed as if my brother Arthur's remark on hearing that I had bought a car - "Percy has more money than brains", was justified but in those days, cars were regarded as merely a passing phase. Later Arthur used to beg a lift to the local hunts but, when the car broke down as it often did, he would hail a passing cart, leaving me to deal with the trouble. Bertha and I have owned a great variety of cars in our lives, from Model T Fords to Hispano Suizas, Stutz, Rolls Royce, Jaguars and Rileys etc. and now we are back to Fords. We loved to get off the beaten track, which was not difficult in those early days.

Soon after we married in 1908, we motored to Southland in a Wolseley car and stayed with Will and Ethel Bond on their station, Argyll, near Waikaia. Later, after leaving them, we made our way across country to Garston and Kingston on Lake Wakatipu. Here we found the little ferry, the old Earnslaw. After considerable opposition, we persuaded them to take the car on board. Planks were found and no difficulty was experienced in doing this. Our arrival at Queenstown caused much excitement as ours was the first car that most of the inhabitants had seen. At first the authorities refused to allow the car to land, declaring that we must return the way we had come, which we refused to do. Finally, the town clerk had the car pushed into a stable and this was locked up, he holding the key. The Council considered the problem, fearing the reaction of the car on the horses using those steep and narrow roads and finally told us that we might continue our journey to Wanaka provided that we travelled through the night on a certain date, to reach Pembroke by 7 a.m. and that they would warn all the horse owners to keep off the road during those hours. We set off from Queenstown late evening and somehow managed to get over the Crown Range by the time allotted. The road was quite incredibly bad, the track soft with boulders blocking it in places, the grade in places made the car boil most of the way, the lamps were quite inadequate and, of course, we had the usual incessant punctures. I don't know now how we ever achieved it. Our car was the first to go over the Crown Range and one of the first to travel through the Lindis Gorge. After spending a couple of nights at Pembroke, we started off for Kurau through the Lindis Gorge. I remember that we had to cross the Lindis river seven times, only one crossing being bridged; we stuck each time and after getting the car out, much time was spent in drying out the plugs and the cylinders. Our car was a two-seater and like all cars in those days, it had a step; to take a third person it was necessary for him to sit on the floor at the feet of the non-driver with his feet on the step. After leaving Pembroke, we picked up a swagger and when late in the afternoon we stuck finally in the Omarama creek, just before reaching that village, the swagger waded ashore and left us to get the car out as best we could. He was an Armenian and our sympathies were entirely with the Turks who, at that time, were slaughtering many of that nation. We never expected to make a trip of any length without many punctures and when the inner tubes were done, we used to stuff the tyres with tussock grass.

A few months later, I went to Te Anau with Carlisle Studholme, Langlow Donkin and others. We took a boat down the Waiau river to within a few miles of Lake Monowai. Here we landed and having arranged for a horse to be swum across the river from Blackmount Station, we managed, with the help of a sledge and flax harness which we made, to haul the boat across to the lake over swampy and stony ridges so that, on arrival, she was in rather a battered condition and needed considerable repair. The country was teeming with life, wild pig and cattle; the pigeons were so plentiful that one could knock them down with a stick and they, with the wild pig, provided most of our food. Many crested grebe were on the water. We set sail for the head of the lake and had hoped to get over to the West Coast across the country but this proved impossible, the bush being impenetrable, so we returned the way that we had come. We improvised a sail but the boat was leaking badly and at one point the bung came out. Luckily it was found at once but we only kept afloat by constant bailing. We returned to Blackmount Station which was owned by Donkin and one night staged a mid-night steeplechase. The horses were in the rough and the obstacles, gates or anything that came our way were brushed aside; the riders were young and probably not too sober.

In 1912 a company was formed as a result of the discovery of a greenstone reef between Otira and Kumara on the West Coast of NZ. My brother-in-law, George Julius, came over from Sydney and acted as consulting engineer. The company had a monopoly of green serpentine for decorative building and also large deposits of nephrite, the jewellery greenstone. An aerial rope expert was brought to NZ from Austria and ten-ton blocks of serpentine greenstone were being brought down from the east face of Griffin Range to a spot in the bush within easy reach of the main road. We thought that our fortunes were made as there was a big demand for the stone from Europe and Australia and we had orders for years ahead. Then came the 1914-18 war. Our Austrian engineer was deported as an enemy alien, the Government refused permits for ships to carry stone in war time, the company failed and the greenstone remains in its reef. Two or three years ago when we were on the West Coast, Bertha and I visited the spot in the bush to which the stone had been transported, having been lent horses by the farmer who owns the land. We found the remains of the workmen's cottages (it was quite a settlement) and also one or two blocks of the stone, almost covered over with growth, one of which we had brought out, had cut in Christchurch and sent up to Hawke's Bay where it acts as a bird bath at Ringstead.

Early in 1914 Bertha and I went to the Dutch East Indies, travelling from Sydney in a Dutch ship and calling at all ports on Australia's eastern and northern coasts, also at Port Moresby in New Guinea, the Dobo Islands, Macassa in the Celebes, etc., reaching Java where we hired a car and toured the island for two or three weeks. In those days the islanders seemed to be well cared for and the country well run - very different from the condition which we found when we were in Jakarta four years ago. We went to Singapore where we were the guests at the Government House for ten days. We had a very gay time there and enjoyed it all. From Singapore we went on through the peninsula, having hired a car with two drivers and stayed with various people en route, Kuala Lumpur, Taiping, etc., to whom we had letters of introduction, and on to Penang.

In about 1904, my two brothers and I formed a Pareora Polo Club and in a primitive way and with mounts of all sizes, started playing in a field in Pareora. Eventually we collected some good ponies and used the South Canterbury Jockey Club's course as our polo ground. I had a string of good ponies with Jack Shaw, later huntsman to the S.C. Hounds and Clerk of the Course of the C.J.C., as my polo boy. For many years the following made up the A Team: A.S. Elworthy No.4; H. Elworthy No.3; P.A. Elworthy No.2; Leslie Orbell No.l. We competed for the Savile Cup on many occasions, both in the North and South Islands, at the last tournament being runners up (Christchurch). In a match against Hawke's Bay, we were even at the end of the last chukka and in the extra chukka which had to be played, our opponents won the first goal. We won all the South Island cups. I had some wonderful games of polo during my leaves in France in the First World War, using ponies lent to me by General Vaughan. Although I have fished a great deal have never been very enthusiastic about it but I remember one or two expeditions with my brother, Herbert, which I enjoyed very much.

We took my two-ton truck fitted with camp beds and gear, covered with a canvas hood. We fished in various rivers in Otago and Southland. Another year he and I went to North Canterbury and got some good fishing on the Hurunui River and Lake Sumner. Shooting has been more of an interest to me than any other sport in spite of my great love for horses. From big game hunting in Africa, deer stalking in NZ to the shooting of driven birds - partridge, pheasant, grouse, etc., in England and Scotland. After my return from Cambridge, I used to go stalking each year, generally with my brothers-in-law, Will Bond and Melville Jameson, in Otago, the Upper Rakaia or the Wilberforce, and it was in the latter that I got my finest head, a 24-pointer, which I gave to the First Life Guards Regimental Mess at Knightsbridge. Some years later I stalked with my old friend Duncan Matheson, Scots gillie and shepherd at Gordons Valley, at the head of the Rakaia. During one of my deer stalking expeditions, Bond, Jameson and I travelled by Munro's horse coach from Kurau to Longslip Station - a long distance - and, on our arrival, Bond proposed making us something really good for our evening meal. With this dish in view, he had brought the necessary ingredients. After much preparation and mixing, he produced a pudding which he tied up in a cloth and put into a kerosene tin of boiling water. We were told that when the pudding came to the surface it was cooked. It came to the surface very soon after being put in. On examination we decided that, perhaps, it would be better eaten cold, so Bill tied it to a tent pole. The next morning the pudding had gone and an untethered horse was dead.

During the years 1924 and 1930 I was a member of two syndicates, one in Berkshire and one in Wiltshire and, in addition had more invitations to shoot than I could accept. Some of my best days each year were with Miller-Mundy at Red Rice, Henderson at West Woodhay, Lord Somers at Eastnor, Barwick at Inholmes, Sir Francis Burdett at Ramsbury Manor and last, but not least, Gifford-Smith, who has given me some wonderful days on Haworth Moor in Yorkshire. Our little grouse moor in Argyllshire gave me much pleasure.

Bertha and I made our first flights early in 1915 at Hendon. With Ada Julius we flew with Graham-White, one of the first men to take up flying in England. Later in the War, I went for a joy-ride with Ken Macdonald, father of Sheila and Michael, who was in the Air Force. We hoped to fly to Scotland but after leaving London ran into dense fog at Kings Lynn where we landed and had lunch. We took to the air again but before reaching the Wash, the engine petered out and we came down in spirals onto a newly sown wheat field. The engine buried itself and the propeller was smashed but we were unhurt. Soon after returning to NZ, after the war, Bertha and I flew to Dunedin. We hired a plane which had come to Timaru as I had to attend a certain meeting and it seemed my only means of getting to it in time. There was no aerodrome in Dunedin, of course, and we had to land on the beach, incidentally, bursting both tyres. The take-off in the afternoon after they had been fixed was not too easy, as the wind was from the sea and we only got up just in time before reaching the waves.

When war broke out in 1914, I enlisted but as I was having recurrent attacks of frontal sinusitis, the medical authorities would not pass me fit for active service. Also, they did not want to take married men with large families at that stage. I solved the difficulty finally by making plans to go to England to enlist there and Bertha and I decided that she and the children should accompany me. I took cabins in the old Remuera due to leave Wellington in four days' time. We dispatched the servants, shut up the house, storing the rugs, blankets, etc. in galvanised iron tanks which we sealed against moths. Incidentally, they came out without harm at the end of four years. I arranged my affairs for an absence of several years, my brother, Arthur, having offered to oversee my farm during my absence as his war effort. I had an excellent manager in Robert Oliphant and realised that all would be well. Nin, (Nurse Jensen), travelled home with us and the voyage, via the Horn, proved uneventful except on one occasion. After leaving Rio, we were chased by the armed merchantman, the Prinz Eitel Friedrich, which was known to be in those waters and which had been doing considerable damage to shipping. The passengers were lined up to take to the boats but the ruse employed by our Captain Greenstreet succeeded. He wirelessed an uncoded message to H.M.S. Carnavon which he thought to be in the South Atlantic, to say that we were being attacked. The Germans intercepted the message and not knowing, any more than did our Captain, the whereabouts of the warship, decided to take no risks and made off. As a matter of fact, the Carnavon was far too far away to have helped us, as I found out later from Tom Williams (Peggy Boye's father) who was on her. It was not a pleasant experience with four very young children on board.

On reaching England we took a house with a large garden bordering on Richmond Park; a lovely spot for children. I went to the War Office, the sinus condition having cleared up completely, possibly as a result of the voyage. The Cavalry General to whom I had a letter of introduction being out of town I, very foolishly, told them to put me anywhere, being convinced as were so many others at the time, that the war would be over before I got into it. I regretted my haste later when I found myself in Infantry, with the Leinster Regiment at Renny Camp near Plymouth. I had never done any infantry work, my experience in soldiering having been with horses - the Cambridge Mounted Infantry and the Canterbury Yeomanry - and I found it little to my liking. Through a friend in the First Life Guards, Lord Tweeddale, the Colonel of that regiment, I applied for my transfer and it was not long before I found myself at Knightsbridge barracks.

Before going any further, I must pay tribute to my colonel, Sir George Holford, who was unfailingly kind and hospitable to us both, entertaining us frequently at his London home, Dorchester House, and at Westonbirt in Gloucestershire. The original Dorchester House stood on the site now occupied by the present Dorchester House and the International Sports Club. Westonbirt, on Sir George's death without heirs, was bought and turned into a girls' school. It was full of treasures, pictures, etc., most of which went to the States, and he had the finest collection of orchids, next to Rothschilds', in England. Bertha and the children remained on at Enmore for three months, then we took a house, Grove Lodge, at Hampstead, and later, after I had been invalided from France, went to live at 47 Cadogan Place, Knightsbridge, then a fashionable part but the house has been turned into flats now.

Soon after joining the regiment I was sent to Hythe, Sussex, to take a course in machine gunnery; the Lewis and Hotchkiss guns being in use then. I sweated blood over the examination as the last officer had failed to pass. On my return to barracks, I was appointed Machine Gun Officer to the regiment and later I had to go through the painful moment of demonstrating the guns to the regiment. On a table, on a platform were placed the two guns; surrounding me were the colonel and officers and in front three or four hundred men in the barrack square. I had to take the gun to pieces, explain the different parts and reassemble them, which by a miracle was accomplished successfully, in spite of my nervousness. Recently I have been reading over some of the notes which I took at that time during the course and have come to the conclusion that my brain was in better working order then than it had ever been before or since.

In addition to the gunnery course, I took a course in bombing at Hythe, again passing successfully. The experience and knowledge gained stood me in good stead later in the trenches when I became Bombing Officer to the Fourth Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders. Soon after joining the regiment I became interested in a certain horse which had been declared a "rogue" by the Rough Riders of the regiment. I said that I would like to mount it. Having secured a stock saddle, martingale, crupper and put a 'monkey' on the saddle I had no trouble. It was then suggested, with some grins, that I should take it into Hyde Park. And then the fun began. The horse charged an oak tree with low branches; this I managed to get him off by hitting him on the head with my crop. He then bolted round the park, but when showing signs of getting tired, I kept him at top speed until he had had more than enough. From then on, I had no further trouble with him and rode him at the head of troop until I went to France. Many of the recruits joining the regiment couldn't ride and knew nothing about horses. The colonel told me to take two troops - about 60 men - into camp on the Epsom Downs to try and instil some horsemanship into them. I took as my second-in-command, Haytor Hames of Chingford, Devon - now Sir Haytor - who has always remained a friend. We had three weeks of intensive work, lecturing and teaching the men to ride. They loved it, especially the cross-country ride, bare back across the Downs, when they were more often off than on their horses. One of my worst experiences before going to France was to march the regiment off Barrack Square - called "passing off". I was horribly conscious that I knew few of the right orders but I had a wonderful Corporal Wright who later became Corporal Major of the regiment. He managed to cover up any mistakes that I made and found the regiment moving as one man. It is all too easy to get them boxed up facing a brick wall.

Early in 1915, when I was still in England, the First and Second Life Guards and the Blues - which regiments constitute the Household Cavalry - arranged to hold a sports meeting on the Epsom Downs. Amongst the events for the officers were various horse competitions. Many officers offered to lend me a mount as I had no horse of my own in England, but I didn't want to borrow. One day I noticed a black charger in my troop in riding school, being ridden by one of my men. Thinking that he looked a natural jumper, I decided to ride him at the sports. I had not long put a leg across him until I rode out to compete with some of the best hunters in England. There was a roar of laughter when I appeared on my charger, but he proved all and more than I had expected and after riding in the finals against the colonel of the Blues, I won the jumping event. Three months after joining the regiment, I went out to France and joined D. Squadron commanded by John Jacob Astor, who has remained my friend ever since. Lord Brassey was in command of the regiment in France with 'Methuselah' Wyndham second in command. He later became colonel of the regiment in England. When Bertha and I were home last - 1954 - Colonel the Hon. and Mrs. Wyndham gave a big luncheon in our honour in London. It was a wonderful gathering. We sat in the places of honour. The Duchess of Abercorn was on our host's left, Lady Brassey (he had died some years ago), John Astor, owner of The Times and the present colonel of the regiment, with other officers, past and present were there to meet us. It was all most heart-warming to be remembered after nearly forty years. Old Lord Leconfield, Wyndham's brother, had died a short while before, but I'm glad that I saw him shortly before when I had lunch with him at Petworth, his fabulous place in West Sussex.

To return to 1915 - we were stationed at Verchocq and had the use of the chateau. Soon after joining the regiment in France, I noticed a wretched child in the village; emaciated, filthy and diseased; her home a hovel. With Jack Mitford as interpreter, I went to see the mayor and arranged with him that the child should be sent to an institution at my expense. She remained there until she grew up and the money that I had left for her with the mayor provided for her. Ada, Bertha and I, when visiting the battle fields many years later, went to Verchocq, had tea with the count and countess at the chateau and went to see the young woman, who we found a healthy, happy wife and mother and very grateful.

All this time cavalry was in use. We were massed at Albert with the other cavalry regiments; 4000 men and horses, for the big break through at the Aegean gap. The awful slaughter of men and horses made it obvious that the day of cavalry in modern warfare was over and from then on, horses were kept at the base and we all joined up as infantry. Many of the officers were "lent" to various infantry regiments. I was sent temporarily as bombing officer to the Seaforth Highlanders, then holding a sector on the Hohenzollern redoubt. There were saps running up from the line to within a few yards of the German trenches. It was winter and I was wearing a heavy sheepskin coat and had grown a large moustache. A few nights previously, a German wearing a sheepskin coat and sporting a large moustache had got into our support lines and had killed the adjutant and returned safely to his own trench. A fortnight's leave had been promised to any soldier who was the means of catching a German in our lines. The night after my arrival when I had made no contacts, at 2 a.m. I was up a sap within bombing distance of the German lines when a NCO of the Middlesex, the regiment adjoining the Seaforth Highlanders, flashed his light into my face and asked me my name and regiment. I told him that I had just been attached to the Seaforth Highlanders. He asked me to find someone to identify me. The previous evening on my arrival I had met, for a moment, an officer of the MiC.C.O. They put me under arrest, "a man behind and a man in front" and as we passed down the lines, the Tommies we passed kept on saying, "Tut it through him" and I thought that I was for it. Then I remembered that our adjutant, "Humpty" Wyndham, was in the support lines, the trouble was to find his dugout. I was allowed to go "under arrest" to the trench where I thought he might be. The Sergeant called down "Is Captain Wyndham here?" and to my intense relief, I heard him answer. "What have they got you for Mutton?", and I told him. He turned indignantly on the Sergeant, "This is one of the officers in my regiment" but of course, the man was only doing his duty. I returned to the front line but, all the rest of the night, the Tommies were eyeing me suspiciously and I heard one man say, "Well, if he is a German, he is certainly a brave man."

Later in 1917, I was invalided home with duodenal trouble and appendicitis. I was operated on for the latter in a military hospital in Belgrave Square, but from then on, because of the duodenal, they would not pass me for active service. I returned to Knightsbridge barracks and helped with the training of recruits and did a good deal of escort duty. As well as being in the escort for King George V and Queen Mary on many occasions, such as the Opening of Parliament, etc., generally riding beside the carriage. I was in the escort for President Wilson and his wife and can remember considerable resentment among the men that he was allowed a Royal Standard, usually reserved for crowned heads only. On one occasion when escorting the King and Queen when the former was talking to the head of the escort, he learnt from Major Clough that his children and ours were at the foot of the Victoria Memorial, in front of the crowd. On enquiring how they were dressed - our four small children were wearing cream rabbit skin coats - the King gave them a special salute. Very often I had to act as King's Guard Officer. This involves riding down the park from Knightsbridge barracks, crossing from Hyde Park to Green Park, where all traffic is stopped by Hyde Park Corner, and on to Whitehall. Having been lent his chargers by J.J. Astor while he was in France, I was the best mounted man in barracks. A King's Guard Officer salutes no one but the King himself. On reaching Whitehall, one's duty consists in dismissing the old guard and inspecting the new - a ceremony well known to visitors to London.

When inspecting the new guard, the men come to the 'Present', and returning their swords to the scabbards, take their time from the officer who also puts his sword into his scabbard, and, at the given time drives it home, the men doing it at exactly the same moment. I was glad I was not the officer who put his sword in the wrong way round and when the time came to drive it home, it jammed - to the great delight of the crowd who were watching.

Early in 1918, there was brought to England by an officer in the Danish Army, a remarkable machine gun which his Government was offering to the English Government for a very reasonable sum. The colonel became interested and instructed me, as Regimental Machine Gun Officer, to inspect it and report to him. I asked to have the support of another officer and chose Reggie Walter. Captain Wyth Sideling put it through the most exhaustive tests in all conditions and we were more than satisfied with its performance and reported to the colonel accordingly. Colonel Holford arranged for a test of the three machine guns - Madsen (Danish), the Hotchkiss and the Lewis, at Rainham. King George was present and many of the high-ups in the Government etc. General Maxse, a Lewis gun enthusiast, came over from France. Our report was read out. General Maxse asserted that I had been inaccurate in some of my statements, but when the test started, they were proved to be correct and the colonel insisted on an apology - and got one. The Madsen gun proved itself superior in every way to the two others then in use - firing continuously in war conditions, in heavy mud and in water - but eventually, because of the difficulty in altering all the machinery for making the guns and ammunition during the war, it was decided to continue with the use of the Hotchkiss and Lewis. We lost a wonderful gun which later was bought by France. Following the trials at Raynham, the matter was brought up both in the House of Commons and the House of Lords. Lord Fisher (Admiralty) and many others expressed much indignation at its having been turned down. I still have a copy of Hansard of that date, giving the debate and also a portfolio of photographs of the Madsen Gun given to me by Captain Wyth Sideling before he left England; a very prized possession.

Although the air raids of the 1914-18 war were not to be compared with those in the Second World War, we had more than our share in London. The Zeppelins were the most un-nerving as they remained stationary overhead. The nearest bomb that came to our home was one which struck the Russian Embassy which backed onto our house. It shook the family considerably but did us no real damage. The children did not leave London, or their nurseries which had three floors above them and were considered to be the best part of a house, high enough to escape the fumes of gas bombs. Their nerves were unaffected; in fact, a raid was welcomed as it meant cocoa and biscuits and a gramophone in the nurseries. The Undergrounds were very congested during the raids, as there were no bomb shelters. Knowing how anxious I was to return to France in some capacity, Jack Mitford, who for some time had been aide-de-camp to General Vaughan, then in command of the Third Cavalry Brigade at General Headquarters at Monteux, arranged with the latter and my own colonel that I should take his place. We used to travel to the various army corps, staying as guests with the different generals. A wonderful experience for a mere captain, as I was allowed to share in all the 'hush hush' information and was shown all the secret maps.

A short time before the armistice, General Vaughan sent me up to Valenciennes to obtain certain information about the horses of the Canadian gunners who held that line. I found the line to be very fluid, the Germans retreating, so I "misunderstood" my instructions to return to GHQ and, with the Canadians, went through to Mons. A piece of insubordination which I have never regretted. I was at Mt Huey four miles east of Mons on Armistice Day and the joy of the Belgians in getting rid of the Germans was beyond belief. They were digging up their treasures, buried during the occupation, wines, laces, etc. and giving a fairly bad time to those, especially women, who had collaborated with the enemy. I returned to Monteux without serious reprimand and eventually to Knightsbridge. General Vaughan and his wife have always shown us much kindness since then. Not wishing to be a peace-time soldier, I got my discharge in January, 1919.

On the 20th January that year our Janet took ill and died a few days afterwards following an appendicitis operation. Of her wonderful character I have spoken earlier; forty years after, she is still so vividly in our memories and so many things at Gordons Valley where I am writing these lines remind us of her. After her death we longed to return to NZ as soon as possible and we sailed shortly afterwards in the Rotorua, making our first journey through the Panama Canal which had recently been opened. Soon after returning to Gordons Valley, Nurse Jensen being still with us, Mr Ivey, then visiting New Zealand, came to us as tutor to our three children. He remained with us for five years, travelling to England with us in 1924, when we took the children home to be educated. They owe very much to his excellent grounding. Mr. Ivey has remained our valued friend. He married later and he and Mrs. Ivey live in Napier.

On November 28th, 1919, Diana was born at Gordons Valley, seven years after Anne. Nin Jensen was still with us and welcomed another baby. We remained at Gordons Valley until 1924 and then shut up the old house once more and went to England with the children, plus Mr. Ivey and Nin. The former remained with us until the boys went to school and Nin a little time longer. When Diana had reached governess age, Nin returned to NZ and later joined her sisters in the States where she died a few years later.

Our subsequent doings are within the memory of our children who will remember Membury and Forbury, the homes that we rented between 1924 and 1930 and Rainscombe which we bought some years later, only to sell again after a time when the NZ Government refused to let us live there unless we sold Gordons Valley, which we weren't willing to do. Bertha, Diana and I returned to Gordons Valley in 1930, the year of the big slump, leaving the three eldest in England and France.

Towards the end of 1918 Bertha received a cable to say that her mother, Mrs. Julius had died. She was a reserved woman of great strength of character, self-effacing and very gentle, whom I have always loved and admired. We were both very sad that she had not lived a few months longer so that we could have seen her again. Twenty years later, in 1938, my father-in-law, Archbishop Julius died. Of him I can say very little that has not been said or written by so many, but I can tell of my great affection for him and of his and Mrs Julius's unfailing kindness to me. He was a man of outstanding ability who could have been a great engineer and inventor (and was), musician, barrister and actor, but who took no pride in his gifts.

In 1933 my dear mother died in Timaru at the great age of 91. She had lived with Edith in Timaru after leaving their home in Christchurch. I think that her long widowhood, in spite of her great loss in my father, had been a happy one. She had travelled considerably and as well as crossing Siberia with Edith, had visited a great many other countries. Up to the very last she kept her great interest in and affection for her family to whom she had always been a wonderful mother.

Following Robert Oliphant, my manager for about 12 years from 1909, I engaged Robert Johnston; another Scot who was with me for 33 years. A splendid man who on retiring, went to live in Timaru a couple of years ago; his son Robin took his place and he is proving a true son of his father. Hubert Johnston, the younger son, is at Tuarangi and Robin's second son, Gordon, is training on Gordons Valley and I hope that we will always have some member of the family here. I must mention Mrs Robert Johnston who has done so much for us and has proved such a loyal friend and also Barbara, Robin's wife, who has done so much to make our visits to the old home so comfortable and happy. Leslie Cox must also be mentioned. He came to us to work under our butler at Forbury, being the son of our head gardener. Later, in 1930, he came out with us to NZ and was our butler for many years, finally joining up in 1939, when the Second War started; we were living at Rainscombe at the time. He is still working for the RAF doing some "hush hush" job near Farnborough. I had the good fortune to retain the services of many of the Gordons Valley employees for long periods. Myers, roustabout for 27 years; Waters, blacksmith for 14 years; Bowman, ploughman and tractor driver for 30 years, etc.

Between the years 1930 and 1938, I made several expeditions with my old friends Bob Wilson and Edgar Stead, both most interesting men possessing a wonderful knowledge of birds and splendid companions. On one occasion we hired a fisherman's ketch at the Bluff and were dropped, with our gear, at Codfish island, a small uninhabited island to the southwest of Stewart Island, with small springs of water, much contaminated however by penguin and sea birds of all descriptions. Edgar was searching for the Cookii petrel which we found and established the fact that these birds breed on this island. The only other place in the world where they are to be found is in Alaska, to which country Edgar sent a number of eggs which we had collected.

We had a narrow escape one day. Having taken a little boat with an outboard engine on an expedition to try and get some photographs of shags which were nesting on a pinnacle of rock out in mid-ocean, there was a heavy swell and after bringing the boat close to the rock on a downward swell, Edgar jumped ashore. The swell began to lift the boat whose stern end caught under a ledge of rock. Bob and I managed to push her free just before she filled. Had we been marooned on the rock no one would have found us. Our journey back was equally difficult. We had decided to circumnavigate the island but found our way to the east cut off by a school of killer whales. They came on at a great pace and so close to us that we could see their eyes and the water pouring through their mouths quite plainly. By some miracle they didn't see us and so passed on their way.

We lived off the island, mostly on fish and birds. I found the penguins most fascinating and would watch them for hours, both the large and the small were on the island in great quantities. Evening after evening they would return from their day's fishing; the sea would be black with them but none would come ashore until their leader had landed and come onto the beach, and then they followed in their thousands up the hill to their burrows. On these islands one came on sea elephants often, they are quite harmless but they have an appalling stench. We spent a wonderful month on Codfish Island - a beautiful spot - yellow, sandy beaches and heavy bush with ratas in full flower covering the hills. We had arranged for a ketch to collect us on a given date. It then left us at half Moon Bay on Stewart Island and from there we went on to Green Island, Ruapuke Island and Jacky Lee Island in a Maori launch. On these islands we collected some red and yellow headed parakeets which Edgar wanted to add to his collection at his home, Ilam, in Christchurch. Their removal was illegal - a fine of £50 on each bird - so much strategy was required. We did the return journey at night, landing the birds at the Bluff in the early hours of the morning and experiencing great difficulty eluding the police nightwatchman on the wharf. Once we got the boxes into Edgar's car, all was well.

Another trip that I made with Edgar, this time there were only the two of us, was to the West Coast of the South Island where we were searching for Rock Wrens. Edgar was an amazing man and I loved to watch him enticing and snaring the birds. He always seemed to know on what tree or branch a bird would settle and he would spend hours of patient watching and waiting, imitating their call. These expeditions gave me the greatest pleasure and no one could have had better companions. Bob was always the keeper of the peace when Edgar and I showed signs of strain. Geoff Buddle of Auckland was one of the whitest men that I have known.

At the end of the Second World War when we had sold Rainscombe and had given up all hope of ending our days in England, I realised that the Gordons Valley house would become a burden eventually, in spite of the fact that so much of it had been pulled down. As it was far too large for our needs and domestic help increasingly difficult to secure, I suggested a small home in the North Island. At first, Bertha would have none of it and said that as living in England was no longer possible, she would rather remain on at the Valley. Eventually, she saw reason. In 1945 I was in the North Island shooting duck with Bob Wilson and decided to look at two possible districts, Tauranga and Havelock North. I disliked the former and in the latter found Ringstead, dilapidated and most peculiar. Recognising its possibilities, I telegraphed to Bertha "I have found our home". Here we have lived very happily for over twelve years, with visits to Gordons Valley three or four times a year which we enjoy. We find that we miss the garden there; the trees are increasingly beautiful and we try to time our visits to the spring when the flowering cherries, azaleas and rhododendrons are glorious and the acres of daffodils are flowering under the trees. Or to the autumn when the deciduous English trees are at their best and the colours far more vivid than in the warmer North Island. My mind often goes back to the days when I planted them.

Following the death of her husband, Melville Gray of Bowerswell, Perth, my much loved sister-in-law Ada Katherine came out to this country to live with us. She was a very ill woman when she arrived and after a big operation in Wellington, the trouble came on again and she died at Ringstead. We were so thankful that she was with us at the end of her life. She had been to us both more than an ordinary sister, marrying late in life. She had shared so much of our lives and travels both in this country and at home and her going was a great loss. Her courage, loyalty and her love we have missed more than I can say. It is a great comfort to have Tony, True and family and Diana, Hamish and the children so comparatively close to us; they keep a loving eye on us and we love to welcome them here whenever possible. Sam's and Anne's visits to NZ in 1958, our golden wedding year, brought us great happiness and we will never forget the wonderful family gatherings. Our one regret is that Audrey and Shaun were not with us too. Our love for and appreciation of our children grow with the years and we are very proud of them. One day, many years ago, when he was congratulating me on our children in the Christchurch Club, John Deans said - using a sheep breeder's term - "Undoubtedly you and Bertha are a good knit." I have always thought that he was right. They chose wisely in marriage for which we can never be sufficiently thankful. Our sons and daughters-in-law are dear to us and we take this opportunity of thanking them for their loyalty and affection which we appreciate. Our twelve grandchildren are constantly in our thoughts and conversation and provide much interest in our old age. All are doing well and promise to grow up fine men and women and the five that are now grown up - Tim, Anto, Dermot, James and Johnny - are doing well in their chosen ways of life and all show signs of leadership and character.