Lancelot GILES CMG HBM [479]

- Born: 6 Jun 1878, Amoy China

- Marriage (1): Marjory SCOTT [411] on 28 Oct 1905 in St Mary Abbotts Kensington LND

- Died: 21 Nov 1934, Tientsin China aged 56

- Crem.: British Cemetery Racecourse Rd Tientsin China

General Notes: General Notes:

Lancelot was educated at Liege Belgium, Feldkirch Austria, Aberdeen, then Christs College Cambridge. His career highlights include: 1899, July: appointed Student Interpreter in China, British;1900: received China Medal for Defence of the Legations during the Boxer uprising; 1903: Vice-Consul, Hankou; 1906: Vice-Consul, Tianjin; 1907: Pro-Consul, Xiamen (Amoy); 1909, June: Acting Consul, Xiamen (Amoy); 1909, August: Acting Vice-Consul, Guangzhou; 1911, March: Acting Consul, Jiujiang then Changsha; 1915: Acting Consul-General, Tianjin; 1917, March: Foreign Trade Department of the [British] Foreign Office; 1919, April: Consul, Changsha; 1925: Consul, Fuzhou; 1927: Consul, Shantou; 1928, April 18: Acting Consul-General, Hankou; 1928, June 4: Awarded the Companion of the Order of St. Michael and St. George; 1928, November: Consul-General [Hankou]; 1930, February - 1934, November 21: Consul-General, Tianjin.)

Two of Lancelots diaries exist from his school days in 1889 & 1891. (On this file and website under Books). They are a fascinating peep into the world of an intelligent boy of those days, at school in Liege. He refers to "going to see the girls" especially at school holidays time, they are thought to include his cousins, the daughters of Arthur Henry Giles, Dolly & Madeline.

Lancelot was serving as a young Student Interpreter in Beijing, when he was caught up was the Boxer Uprising and the Defence of the Legations from June 20th to August 14th 1900. He was witness to the destruction of the Hanlin Library by the Boxers in which was lost the Encyclopedia Maxima (The Great Standard of Ta Tien or the Encyclopedia Maxima, was comprised of 917,480 pages in 11,100 bound volumes. Produced by a commission of over two thousand scholars in 1408, it purported to record all knowledge of the Confucian canon, Buddhism, history, philosophy, astronomy, geography, medicine, and the arts).

Lancelot described in his diary, published in 1970, the situation as follows: "An attempt was made to save the famous Yung Lo Ta Tien [now spelled Yong Le Da Dian], but heaps of volumes had been destroyed, so the attempt was given up. I secured vol. [section] 13,345 for myself."xi

However it must have been a great distress to his family and friends in England to read the early newspaper reports of the Boxer Rebellion and Defence of the Legations. The Legation in Peking was reported to be completely overrun in savage fighting, "All Were Killed" said a subheading, there were no reports of survivors.

Roll Of The Dead.

List of the English Speaking Victim's.

More or less accurate lists have been published of the British residents in the Legations at Peking and the Foreign Office supplies the appended list of those who were known to be at the British Legation on May 10.

Sir Claude Macdonald . . . . .

The following student interpreter's: . . . . . Lancelot Giles . . . . .

Ref: Extracted from the Western Mail 17 July 1900. also Leeds Mercury 17 July 1900, The Times 17 July 1900.

Fortunately Lancelot survived the siege and was decorated for his bravery.

An extensive illustrated description of the Boxer Rebellion is to be found on the following web site:

http://www.historikorders.com/chinaboxer.htm

Ref; His diary. http://library.anu.edu.au/search/?searchtype=t&searcharg=siege+of+the%2BPeking%2Blegations%3A%2Ba%2Bdiary&searchscope=8&SORT=D&extended=0&SUBMIT=Search&searchlimits=&searchorigarg=tThe%2Bsiege%2Bof%2Bthe%2BPeking%2Blegations%3A%2Ba%2Bdiary

The Seige of the Peking Legations: A Diary by Lancelot Giles; L. R. Marchant

Rosamond Stewart his grandaughter writes in 2008:

"Lancelot had a wonderful happy life with Marjorie in his different consulate jobs around China. There were racing activities, owning horses, parties, dinners, acting and sports to keep them busy. He officiated in the marriages of his two daughters in the All Saints Church Teintsin, and even after he was found to have an inoperable bowel cancer in March 1934 he officiated as Consul General till November 21, 1934 working from his deathbed. A calmer more loved man you could not have found and he was much respected and missed". They had regular trips home to England to see their daughters who were schooled there.

Deaths

Giles - on November 21, 1934, at 1 Racecourse Rd, Tientsin, Lancelot Giles, C.M.G., H.B.M. Consular General, beloved husband of Marjorie Giles.

Shanghai 28 Nov 1934

The Times 22 November 1934 pg 19 col C.

Mr Lancelot Giles.

Our Peking Correspondent telegraphs that Mr Lancelot Giles, CMG, Consul General at Tientsin, and died there yesterday at the age of 56.

The son of Prof H. A. Giles, the eminent sinologue, who was himself for a long time in the Chinese Consular Service, and the brother of Dr Lionel Giles, of the British Museum, he was born at Amoy in 1878. He was educated abroad and at Aberdeen University and Christ's College, Cambridge, and was appointed to the Chinese Consular Service in 1899. He became Vice Consul in 1914. Consul in 1918, and Consul General in 1928. He had been Consul General at Tientsin, with a short break, since 1930. In 1900 he received the China medal and clasp for the defence of the Legations at Peking. He married Miss Marjorie Scott, and had two daughters.

Death of Tientsin Consul General.

Mr Lancelot Giles Passes Away After Long Illness.

Tientsin Nov 21.

The death occurred this morning, at the age of 56, of Mr Lancelot Giles, C.M.G., who has been British Consul General here since December, 1929. Not only the British, but the entire foreign community, as well as his many friends among the Chinese, learned of the news with real regret. Mr Giles had been ill for some time and seriously ill since last March, his complaint causing him much suffering.

For some time, Mr Giles had been carrying on many of his consulate duties from his bedroom in a manner which earned him the admiration of his staff and all with whom he had to deal. Much sympathy is felt for his widow and his two daughters. His wife and one of his daughters were with him this morning and the other daughter recently came here from Singapore to see him.

Mr Giles was China born his father, Professor Herbert A. Giles, having been stationed at Amoy in the consular service. Mr Giles was born there on June 6, 1878. He was educated at Aberdeen University and Christ's College, Cambridge, and in 1899 was appointed to the consular service in China. Five years later, he was appointed a Vice Consul, became a full Consul in 1918, and Consul General in 1928. He served in many ports in China during his career and was in Peking during the Boxer troubles of 1900. For his services during that troublous time he received the China Medal and clasp, having played a prominent part in the defence of the legations.

Mr Giles had a brother in the consular service in China who died a few years ago, Mr Bertram Giles who was Consul General at Nanking during the troubles of March, 1927. It was during an attack on the consulate that he was shot, his injuries necessitating him going on sick leave to England, where he died not long afterwards.

Reuter.

Shanghai 28 Nov 1934

Lancelot Giles

A Shanghai Tribute

Shanghai, Nov, 22.

A fine and full career in H. M. Consular's Service has ended in the death of Mr Lancelot Giles. The end was characteristic of a man of supreme courage and devotion to duty. Although so long ago as March last, Mr Giles was stricken by the disease which he knew to be mortal he stuck to his post and, through the long weary months, even to the time when his malady forced him to take to his bed, he discharged the responsibilities of his office. His friends have been filled with deep admiration for the splendid example he thus set. That admiration, which now gives way to sincere sympathy, has been extended to his wife whose own fortitude and support of him has been unwearied and true to the highest traditions of her kind. Mr Giles was one of the sons of a distinguished sinologue, Professor H. A. Giles, whose name is a household word to men of the Consulate Service. His late brother, Mr Bertram Giles, was a member of that Service and died in harness, after being wounded in the Nanking affair of 1927.

Another brother, Mr Lionel Giles, eminent orientalist at the British Museum and, like his father, a Chinese scholar. Yet another brother, Colonel Valentine Giles, served in the Royal Engineers and won distinction in the Great War and earlier in the Tibet Expedition of 1904. Mr Lancelot Giles, after varied experience in the Service, showed his mettle in the difficult post of Acting Consul General in Hankow in 1928 at a time of considerable strain. He later went to Tientsin in the substantive rank. There, by his general enthusiasm for the Port and his abiding interest in local affairs, he gained the confidence of his countrymen to a remarkable degree. He was a man who combined efficiency in his work with great social gifts. He took an active part in the sporting life of the community and, when the blow fell and they were aware that a term had been put to his sojourn with them, their grief was mitigated only by the wonderful inspiration of his continued presence at his post despite the affliction visited upon him. In serving his country Lancelot Giles displayed to the full the qualities expected of men of his calling. Transcending all was the simple heroism which enabled him to show a clear, unclouded mind in the faithful discharge of his official routine to the end of his time. His fellow countryman salute his memory with deep affection and pride.

Unattributed news paper article.

1934

Death of Mr Lancelot Giles

British Consul General in Tientsin.

Career Of Great Usefulness and Distinction Closes.

It is with sincere regret that we record the passing of Mr Lancelot Giles C.M.G., the British Consul General in Tientsin, at the age of 56.

The half-mastered flags over the Consular residence, the Gordon Hall, and other buildings, hanging limp and folorn in the still air, were the first notification many Britons had of the sad event - a sadness somewhat relieved perhaps, in the reflection that at last release had come to a gentleman who had suffered much in recent months. Mr Giles became very ill some time ago and went into hospital earlier in the year for an operation. His condition was such that nothing beyond temporary palliation (sic) was possible, and though he had appeared at various public functions and maintained a courageous interest in all that was going on, he had been virtually an invalid ever since, tendered watchfully and unremittingly by Mrs Giles. He passed away in the early hours of yesterday.

The late Consul General, who was one of the numerous sons of the famous Sinologue, Dr H. A. Giles, was born in China about June 6, 1878. He studied at Aberdeen University and Christ's College Cambridge, passed the competitive examination on June 7, 1899, and was appointed a student interpreter in China in the following month of the same year. He received that China Medal with clasp for the Defence of the Legations during the Boxer upheaval in 1900. After serving for a period as Vice Consul in Hankow, to which he was posted in 1903, Mr Giles came to Tientsin as Vice Consul for the first time in 1906. From here he went as Pro-Consul to Amoy in 1907, and was appointed Acting Consul there in June 1909. After serving as acting Vice Consul at Canton from August 1909, till March, 1911, he became successively Acting Consul at Kiukiang and Changsha, to return to Tientsin as acting Consul General in 1915. Thereafter, from March, 1917 to March 1918, Mr Giles was employed in the Foreign Trade Department of the Foreign Office, and on his return to China was appointed Consul at Changsha in April 1919.

His formal appointment as one of H. M.s., Consul's in China was notified on March 1, 1922. From Hunan Mr Giles proceeded to Foochow in 1925 and then to Swantow, 1927-28, whereafter he became acting Consul General at Hankow areas from April 18, 1928. He was decorated with the C.M.G. on June 4, 1928, and appointed Consul General in China in November of the same year. He came here as Consul General in February 1930.

During his four years in this port as Consul General, Mr Giles played a very conspicuous part in many of the chief interests of the community. Few Consul General's of any nation have more closely identified themselves with the social and sporting life of the community as well as with official activities. For a time he acted as Senior Consul, and his personal prestige among his colleagues, as among the Chinese and foreign officials and residents generally, was very high. He was a man of great force of character but also of great geniality and charm. There was scarcely a worthy activity in the Port which did not engage his own lively interest and participation. Among other offices which he held, for instance, was that of Chairman of Stewards of the Race Club, an onerous post which Mr Giles filled with marked distinction and success. Both he and his family were exceedingly keen on racing, and the stable with which they were connected was markedly successful from the very first. As Chairman of the Committee of Management of the Grammar School, as head of his National Society, as President of various sporting Clubs, and in many other ways he figured prominently in many different activities over and beyond his important official duties as Consul General. Witty and urbane in his personal contacts, he carried the same faculties to his task as Chairman of meetings of the Ratepayers of the B.M.A. and of the Race Club, but when he had to vacate the chair and fight for a case or a cause which appealed to him he could turn that wit upon his opponents, without any undue loss of urbanity, to most telling effect. The Press has cause to remember him with gratitude, for he usually had a copy of his remarks available: a consideration which was peculiarly valuable since Mr Giles was perhaps one of the most rapid speakers to be found in this part of the world.

To Mrs Giles and her daughter, who was but recently married to Mr Ivor House, the most sincere and heartfelt sympathy of the community will be extended in the irreparable loss they have sustained.

The funeral will take place at Racecourse Road Cemetery this afternoon at 1.30, and there will be a service in the Chapel before cremation.

Unattributed news paper article.

Lancelot Giles - An Appreciation

Lancelot Giles, the youngest of the six sons of Prof H. A. Giles, Emeritus Professor of Chinese at the University of Cambridge and a former member of the Chinese Consular Service, was born in China as were all his brothers. During the course of his long career in this country it fell to his lot to be stationed in many of the smaller ports and it was for his services in these ports that he was made a C.M.G. in the Birthday Honours List of 1928. From the time when he received his baptism of fire in the Siege of the Legations of Peking as a Student Interpreter he had to face many difficult and dangerous situation. He was in Canton at the time of the abortive first revolution, was Consul in Foochow at the height of the students anti foreign agitation and in Hankow (Acting Consular General) during the revolt of General Li Tsung Jen. which for a time threatened the safety of that city. He was also Acting Consul in KiuKiang and Consul in Changsha, places where delicate situations were constantly arising. It was in dealing with such situations that Giles excelled. He had a calm courage which inspired his own nationals with confidence and the officials of other nations with respect; he was the least fussy, the least excitable of men. His conception of his duty was always perfectly clear and carried out fearlessly and without regard to his own interests. He was a great believer in the power of personal example and in the truth of the maxim "Noblesse Oblige". Where ever he was stationed and under what ever circumstances he endeavoured to lead always the normal and full life of an English gentleman. He found time to combine with his official duties an interest in the world and local affairs and in many branches of sport. A most companionable man and a regular supporter of "club life" Giles was one of the most approachable of men and an excellent host. His house was first and foremost the home of his family in which their friends were always welcome. He died uncomplaining and in harness as he wished to do. He will be remembered as an English gentleman who did his duty.

Unattributed news paper article.

Shanghai 5 December 1934.

Tiention Funeral for Consul.

In simple and impressive military ceremonial the remains of the late British Consul General in Tientsin, Sir Lancelot Giles, were cremated in the Racecourse Road Cemetery in Tientsin last Thursday afternoon November 22.

Fall consular and military and other official representation attended the funeral under the direction of Bishop Norris, Chaplain Duncan and the Rev. Mr Walker.

The casket containing the remains was borne by a detachment of the Queen's Regiment now in Tientsin. The cortège passed along the path lined by a guard of honour composed of members of the Tientsin British Municipal Emergency Corps under the command of Captain W. Ridler and Sergeant Major W H E Frost.

After prayers in the Chapel, the funeral procession formed up and proceeded to the graveside followed immediately behind by Mrs Giles the widow, supported by Mr S. G. Beare who has been acting British Consul in Tientsin for the past few months. Mr I. E. House son-in-law of the widow followed.

The casket draped with the Consul General's flag was next . . . . . the procession and carried by a detachment of the Queen's.

Memorial Fund

To the Late Mr Lancelot Giles C.M.G.

Contributions To Dr Barnardo's Homes.

Amount previously acknowledged $515.00

Miss Mary Court $5

Mr G Gordon Brown $5

Mr and Mrs P T Lawless $5

Mr and Mrs Fergan $5

Mr and Mrs H. McClure Anderson $10

Mr and Mme Robert L. Samarcq $10

Mr and Mrs Ernest W. Fitchford & Ray $10

Mr and Mrs T Black $5

Mr and Mrs R W. Roberts $20

Mrs E. Pennell and family $10

Brigadier A. J. Ellis $10

Mr C G C Asker $10

Unattributed news paper articles.

Research Notes: Research Notes:

The Boxer Uprising and Western Interests

The siege of the Allied Legations by the Boxers, known in China as the Yihetuan Movement, in the summer of 1900 was not an isolated series of events. It must be seen as one expression of mounting tension between the Chinese people and government and the Western powers with their commercial, military, and religious aspirations. Because the siege involved diplomatic missions of European nations, the United States, and Japan, it attracted worldwide attention in a way that previous incidents had not. For the Chinese, however, the two-month episode was, in the words of one historian, "of trivial significance," because it was eclipsed by the aftermath of humiliating concessions and crushing reparations.ii

Nineteenth-Century China witnessed a recurring cycle of "fragmentation and reform" as the Great Britain and other powers resisted efforts of the Chinese to curb the opium trade, commercial exploitation, and missionary activity.iii Far too complex to detail here, one can recall the Opium Wars of 1839-1842 and 1857-1858 in the southeast, the Taiping Movement of 1851-1866 in the central region and centered in Nanjing, the Muslim Revolts of 1855-1873 in the northwest and southwest, along with the loss of satellite states. All contributed to the effort to strengthen the imperial government through military preparedness and limited reforms. This program suffered setbacks later in the century in disastrous wars with France (1880s) and Japan (1894-1895), as well as ominous threats from Russia.

The carving up of the periphery of the Chinese empire, and the Yangzi River with treaty ports and concession regions brought both some adaptation of Western administrative practices and much antipathy to reflective Chinese citizens. A brief attempt at reform by Emperor Guangxu under the leadership of Kang Youwei in the summer of 1898 was stifled by the empress dowager Cixi who had in effect rul ed China for the Qing dynasty since the 1860s. The cumulative frustrations of all these factors seemed set to break out again.

Shandong province that had seen perhaps the greatest degree of recent encroachment by Western powers was the source a revived popular movement against foreigners in general, missionaries in particular, and most of all Chinese who had adopted Christianity. Beginning in 1898--the "Fists United in Righteousness," as they called themselves, or "Boxers," as they were known in the West--drew upon secret-society and magical rites, reminiscent of the Small Sword Society, Red Lantern groups, and the White Lotus sect of earlier times. Claiming to be invulnerable to bullets and swords and believing in folk mythologies that involved religion and street rituals, the Boxers called for the revocation of special considerations enjoyed by Chinese and European Christians and by 1899 had begun to destroy property and kill converts as well as foreigners in Shandong and Hebei provinces.iv At the same time a massive Yellow River flood seemed to call for desperate measures against nature and the foreigners.

The Western powers were shocked by Boxer Uprising but saw in the crisis an opportunity to extend their influence and ensure their security. Thus, they looked to the Qing Government to employ serious strategies to quell the Yihetuan Movement, on the one hand, while at the same time through negotiation (28-20 May) they prepared their own forces to take action. On 31 May more than 400 men of the Allied forces entered Beijing to "protect the Legations."v Shortly thereafter the Boxers entered the capital, preceded by scores of Western missionaries and thousands of Chinese converts. On 10 June the Allied force--consisting of 2,064 men representing Austria-Hungary, France, Great Britain, Germany, Italy, Japan, and the United States of America under the leadership of British Admir al Seymour--landed at Dagu, Tianjin. The next day the Boxers killed a Japanese diplomat; and the following day the Allied force took the forts at Dagu that guarded the entrance to Tianjin, the lifeline and railhead to Beijing. On 20 June a German minister was killed on his way to the the ZongliYamen [Office for the Management of Business of All Foreign Countries--or Foreign Commerce Office] in the the capital. The next day the Qing Government felt compelled to declare war on the Allied forces and ordered the imperial Qing soldiers and the Boxers, some 200,000 strong, to lay siege to the Legation Quarter, defended by about 450 guards. The siege would last until relief from an expeditionary force that entered the capital on 14 August.vi

The Siege and Destruction of the Hanlin

The Siege of Peking--called by one historian, "the episode best remembered abroad" of the Boxer Uprising--was a dramatic event that captured worldwide attention that minor incidents did not.vii It is not within the scope of this paper to recount the actual siege, its lifting, or its aftermath exciting though it may be. Once the attacks began in earnest with the encouragement o f the Empress Dowager, the Allied hostages and their Christian Chinese converts, prepared for a siege of unknown duration, by consolidating their small area of control and fortification by withdrawing from the exposed extremities and resettling nearly 3,000 people into the remaining quarters.

Not long after the first assault when Sir Claude MacDonald emerged as commander-in-chief, on Saturday, 23 June, the Chinese tested the perimeter of the western side of the enclave by burning an area of native dwellings south of the British Legation. Fire became a new frightening tactic. To the north of the Legation was situated the Hanlin Yuan, a complex of courtyards and buildings that housed "the quintessence of Chinese scholarship . . . the oldest and richest library in the world."viii A late morning fire there was quelled and the compound cleared of Chinese troops.ix The British became worried that the incendiary intentions of the attackers might include this vulnerable site, the buildings at some point being only an arm's length from the British building walls. On th e other hand the Allies, knowing of the Chinese veneration for their cultural heritage, felt that they would face no destructive threat from that direction. x

Yet, on Sunday, 24 June, when the winds shifted to come strongly from the north, the unanticipated happened: the buildings of Hanlin, and the Library that abutted the British building, began burning on a bigger scale than that of the previous day. As Fleming summarizes contemporary descriptions, "The old buildings burned like tinder with a roar which drowned the steady rattle of musketry as Tung Fu-shiang's Moslems fired wildly through the smoke from upper windows." Through a hole in their own wall that was near one of the Hanlin cloisters, the British Royal Marines hastened through the breach, followed by a motley crew of others who formed a human bucket brigade. To quote Flemming again,

Some of the incendiaries were shot down, but the buildings were an inferno and the old trees standing round them blazed like torches. It seemed as if nothing could save the British Legation, on whose security the whole defence depended. But at the last minute the wind veered to the north-west and the worst of the danger was over.

The fire-fighters had already demolished the nearest of Hanlin halls. The next one was the library.

An eyewitness, Lancelot Giles, son of Herbert A. Giles, described the situation as follows: "An attempt was made to save the famous Yung Lo Ta Tien [now spelled Yong Lo Da Dia], but heaps of volumes had been destroyed, so the attempt was given up. I secured vol. [section] 13,345 for myself."xi

The Chinese have suggested that the British destroyed the library as a defensive measure; however, the British account, noting the direction of the wind, have maintained that the "Chinese set fire to the Hanlin, working systematically from one courtyard to the next." Important as this issue is, it is eclipsed by the significance of the Hanlin library itself and of its destruction to f ire and booty collectors.

The Contents of the Hanlin Library

BOXER WAR

The Boxer War 1900-1901

In the broad history of foreign imperialism and internal social unrest in China, the Boxer War was very brief but of tremendous importance. The origins of the boxers can, and have, been traced back to the early part of the nineteenth century.1 <http://www.bris.ac.uk/Depts/History/Projects/Boxers/>. The war, meaning direct contact between Chinese and foreign military men, occurred only in the latter half of 1900 with punitive expeditions reaching into 1901. In any analysis of such a war, lack of sources is a problem. In this case, the nature of the war accentuates this problem. Western sources from the siege of the legations, such as Indiscreet Letters from Peking, by B.L.Putnam Weale and Behind the Scenes at Peking by Mary Hooker, can only tell us about the part of the overall war in which they took part, and only from a very limited viewpoint. Furthermore, boxer sources are scarce and the variety of events happening simultaneously during the war period makes it all the more confusing. As a result, both western and Chinese historians have varied in their opinions of the significance of the war, its reasons, conduct and its results. Jerome Chen in 'The Nature and Characteristics of the Boxer Movement,' states that the 'Battle of the Concessions provoked the Chinese gentry to risk a palace revolution. And the peasantry to plunge itself into an anti-foreign campaign,' while also quoting Yun Yu-ting's claim that the Boxer uprising and war was 'the most important religious uprising in the world as a whole to take place in the present century.' This view is in sharp contrast to the pervading contemporary western view of the war, blamed on the Chinese for 'crimes unparalleled in the history of mankind.'<http://www.bris.ac.uk/Depts/History/Projects/Boxers/>. The war was a passionate affair where emotions and cultures clashed as well as weapons.

While short-term reasons for the war are quite specific, the longer-term crisis in the Chinese countryside was caused by a combination of socio-economic disaster, governmental weakness and unwanted foreign intervention through missionaries and trade. The drought, famine and flooding in the Northern plain coincided with the tax crisis brought on by China's defeat in the Sino-Japanese war in 1897, leaving large tracts of the population desperate. Such fear was harnessed by boxer groups into a hatred for foreigners and their religion. This hatred was exacerbated by the often confrontational behaviour of missionaries and Chinese converts to Christianity. It was also allowed to grow because of divisions within the court over appropriate action. The rapid events of 1900 occurred within an environment of increased animosity towards foreign Christians and their native counterparts. By May this had reached a high level shown in the killing of 4 French and Belgian railway engineers fleeing from Baoding to Tianjin on May 31, and of 2 missionaries on June 1.3. <http://www.bris.ac.uk/Depts/History/Projects/Boxers/> A crucial event happened on May 31, when the court gave orders to annihilate the boxers. This order was completely reversed after the legation guards were summoned by the foreign powers, thus strengthening the position of pro boxers within the court. Purcell also adds that bringing up the guards made 'despatch of reinforcements (the Seymour expedition,) necessary and to secure their retreat the Dagu forts had to be taken, which in its turn led to war.'<http://www.bris.ac.uk/Depts/History/Projects/Boxers/>. Whether true or not, the Qing government remained indecisive until June 10 when Admiral Seymour left Tianjin with about 2000 men without Chinese authorisation. By June 18, he was still bogged down half way to the capital and decided to return to Tianjin, finally arriving on June 26th. Meanwhile, large numbers of Boxers were heading into the capital. On June 13, the Southern Cathedral was burned with Chinese Christians inside. Tension reached a head after June 16 when the Empress Dowager held conferences moving towards war and on June 21st she issued the 'declaration of War', renaming the Boxers 'yimin' or 'righteous people' and putting them under the control of Prince Zhuang.<http://www.bris.ac.uk/Depts/History/Projects/Boxers/>.

The 'boxer war' that followed has been portrayed, particularly by popular Chinese historians after 1949, as a war of nationalism against an unwanted foreign invasion.<http://www.bris.ac.uk/Depts/History/Projects/Boxers/>. However, immediately after June 21st, the declaration was renounced by several regional leaders including Li Hung-Chang at Canton, Liu K'un-I at Nanking and Yuan Shih-Kai in Shandong. It was, according to them, 'luan-ming,' illegal since it hadn't come from the throne, and separate treaties were agreed in these regions. This seems to imply that the Chinese did not unanimously support the boxer war. Yet, there are some aspects of the boxer cause that could be called nationalistic, not least the simple desire to 'expel the foreigners,' and we must consider how these are shown in areas of the war itself. Similarly, from the western side, the aim of the war has often been seen as an effort simply to stop the persecution of foreign diplomats. Sabine Dabringhaus described the war as when 'a modern, industrialised power fought against a popular protest movement, not against another state and not for domination, but for the restoration of the status quo ante.'<http://www.bris.ac.uk/Depts/History/Projects/Boxers/>. A question also worth considering is to what extent the war, from the western side, was indeed a 'war of pacification,' whether there were other motives behind the multi-national expedition to the east, and how all these motives were manifested in warfare.

In his book 'History in Three Keys: The Boxers as Event, Experience, and Myth,' Cohen divides up the complicated proceedings of war into a series of different sections. These divisions are very useful in an examination of western and Chinese behaviour during the war. Yet both the Seymour expedition and the taking of the Dagu forts served more as reasons for war rather than acts of war in themselves. As has already been mentioned, Purcell calls these acts instrumental in the decision to go to war. They also steeled the Qing court out of their indecision into action against the western powers. The first major confrontations between Chinese and foreign militants occurred in the Capital and in Tianjin. In the latter, Chinese attacks on foreign settlements had begun on June 17 1900. The situation remained particularly precarious until the arrival of a relief force on June 26th. Although this force, some 5-6,000 strong, was not able to enter the town immediately, the siege ended on July 13th, dealing a large blow to the boxers in that area. This episode of the war can, on the one side, be seen as aggression towards foreign presence, and on the other as a war of survival before the relief force arrives. In terms of warfare, it follows a relatively conventional pattern of siege and relief. Yet, it is important to remember that such aggression was not necessarily borne out of mass nationalism. Mass hysteria during this period blamed foreign presence for ecological disasters, and consequently, the belief that conditions would improve with the extermination of foreigners was rife. This might, in part, explain the cruelty and viciousness with which captured foreigners and Chinese Christians were treated. This behaviour was not exclusive to Tianjin; Olivia Ogren, writing about Yongning, tells of a local clerical worker in a mission who 'had been caught by the Boxers, dragged from prison, where the official had sought to protect him, and beheaded. His head was nailed to the city wall, until his widow was released from prison when she took it down.'<http://www.bris.ac.uk/Depts/History/Projects/Boxers/>. While I hasten to add that it were not only the Boxers to blame for appalling 'war crimes,' as shall be seen, such cruelty was rife and an infamous phenomenon of the boxer war.

Perhaps the best known aspect of the boxer war is the 'Siege of the Legations.' While Tianjin, the attack on the Forts, and Seymour's expedition were militarily conventional, proceedings in Beijing were extraordinary and unpredictable. After the declaration of war on 21st June, over 3,000 Catholics, along with 43 Italian and French marines, blockaded themselves inside the Northern Cathedral in fear of their lives. The Cathedral was then besieged by over ten thousand Boxers under the command of Prince Duan. They used all means available, mines, rifles, cannon and fire to force entry but were unable. Interestingly, this gave rise to a myth that those inside the Cathedral possessed magical powers, a psychological blow to the Boxer cause, so reliant on spiritual beliefs. Elsewhere in the capital, following the murder of Baron von Ketteler; shot dead on the way to the Zongli Yamen, missionaries and diplomats fled to, and found themselves trapped in, the legation quarters. Defended by around four hundred soldiers and over 100 volunteers, several thousand civilians were besieged from June 20th to August 14th. This ferocity of the siege, well documented by westerners in diaries and letters from within the legations, continued almost unabated with only a brief lull in the fighting in July. Furthermore, The besieged were faced by, at least relatively, organised Qing troops as opposed to a disorganised boxer rabble.<http://www.bris.ac.uk/Depts/History/Projects/Boxers/>. On the surface, this part of the conflict, too, seems like a simple act of Chinese aggression against foreign presence and a war of survival for those inside the legations waiting relief. We see, during this period, further examples of boxer violence and brutality, yet significantly we see similar brutality displayed by foreign military men. An example of this can be seen in the diary of the contemporary Lancelot Giles,

'Last night twenty Chinese were captured. Three were shot; but the French corporal said it would not do to waste so many precious rounds, he killed fifteen with his bayonet. Two were kept to be examined.'10 <http://www.bris.ac.uk/Depts/History/Projects/Boxers/>.

A further interesting fact about the siege was the role of the leaders, Dong Fuxiang and Ronglu, in making sure the legations were never taken. It has been argued by various historians that, considering a boxer victory in this part of the conflict a foolish move and one tempting heavy consequences, both leaders made sure never to press the legations into submission. This slightly thwarts the notion of the war being a manifestation of unanimous nationalism in the face of a common enemy.

In a question about mixed motives for the boxer war, arguably the most interesting period to consider is that after mid August and the arrival of the relief force. By this time, the majority of the Boxers had drifted away into obscurity. After initial victories on their way to the capital, the force, some 20,000 men half of whom were Japanese were left to mop up the pieces. This force was joined in late 1900 by further western troops, in order to begin what was to be the last stage of the boxer war, the punitive operations. This was to be performed under the command of Field Marshall Alfred von Waldersee. Several aspects of the foreign action during this period require more explanation than simply saying that it was a mission of pacification, to rid China of the boxer threat. Notably unlike much before, the punitive expeditions met with very little resistance from Chinese militants and clashes with the Qing army were rare. When they did occur, such as near Tianjin on August 20th 1900, the Chinese suffered heavily.11 <http://www.bris.ac.uk/Depts/History/Projects/Boxers/>. This brings into question the whole notion that this was still war. Whether it was, or merely punishment and revenge, the level of destruction throughout the North was on a vast scale. The mainly German force drew up a triangle between Beijing, Tianjin and Baoding, the 'occupied' zone, and systematically began killing people 'on mere suspicion of being boxers.'12 <http://www.bris.ac.uk/Depts/History/Projects/Boxers/>. In October 1900, 26 villages between Tianjin and Baoding were burned,13. <http://www.bris.ac.uk/Depts/History/Projects/Boxers/> while Waldersee himself estimated that about 300,000 civilians were left homeless after allied advance from the sea to Beijing. Sabine Dabringhaus suggests three reasons for such behaviour. First, the deep misconceptions about the 'Yellow Peril' meant hatred for the Chinese lead to excess cruelty. The soldiers themselves, spurred on by the words of Kaiser Wilhelm,14. <http://www.bris.ac.uk/Depts/History/Projects/Boxers/> embarked on what they thought was a war of civilisation shown in the 'Kolnische Zeitung' of October 4 1900, which called the boxer expedition a defensive act of the civilised nations against the 'Asiatic hordes.'15. <http://www.bris.ac.uk/Depts/History/Projects/Boxers/> This period could also be seen as a war of prestige. Waldersee only arrived after the legations had been freed. Keen to show the German army as an efficient fighting unit, their policing role was made on a giant scale. In the words of Dabringhaus, 'the German war in China was also a war of prestige in the circle of the great powers and for domestic acceptance of a flamboyant type of Weltpolitik.' Ulterior motives for war are evident. Furthermore, not merely in the 'occupied zone' but in the capital as well, plundering on a large scale was performed by everyone. Beijing was literally divided up into zones of plunder. One spectacular example is of Sir Claude Macdonald, a noted British Minister, who supervised the removal of Chinese treasures from the Imperial Palace.16. <http://www.bris.ac.uk/Depts/History/Projects/Boxers/>

It is impossible to describe the boxer war in broad statements due to its different stages and different causes. Nationalism born out of xenophobia and crisis might explain part of it. Religious hysteria might also have been a cause. Governmental weakness and foreign interference certainly were causes. The sieges of Tianjin, the cathedral and of the Legation quarter were all in an effort to o ust unwanted foreigners, while the foreigners themselves were fighting for survival. After the relief of the legations, the war took on a different pattern. Theoretically, a war of 'pacification,' motives of prestige and plunder were to be seen. Misconceptions meant many saw it as a mission to 'civilise' the backward natives, while others were merely out for vengeance. Significantly, the authority of the Qing government to rule was never threatened throughout the war or after. With the exception of Russia, not one of the western countries fought a war for colonial territory. Russia, on the other hand, took advantage of China's internal crisis to extend her gains in the west. By July, there was Sino-Russian conflict in the three Manchuria provinces, with Russian armies finally entering Mukden on October 1st. Apart from this, the geography of China remained very much the same. Yet China was irrevocably altered. The Boxer Protocol put a huge and ultimately impossible burden on the Qing government directly leading to its fall a little over a decade later, and the beginning of a new era for China. Furthermore, the ' cleansing operations' of the punitive forces, and the mobilisation of mass support by the boxers bear ominous similarities to far greater conflict later that century, and give rise to the new notion of 'total warfare.'

1.See Victor Purcell, The Boxer Uprising: A Background Study (Cambridge 1963), and Joseph W. Esherick, The Origins of the Boxer Uprising (Berkeley 1987)

2.Jerome Chen, 'The nature and characteristics of the boxer movement: a morphological study', Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies v.23 (1960), p287&290, Sabine Dabringhaus, 'An Army on Vacation? The German War in China, 1900-1901', Anticipation Total War; The German and American Experiences, 1871-1914 ed. Manfred Boemeke, Roger Chickering & Stig Forster (Cambridge 1999) p468

3.Paul A. Cohen, History in Three Keys: Boxers as Event, Experience, and Myth (New York 1997 p47

4. Victor Purcell, The Boxer Uprising: A Background Study (Cambridge 1963) p246 cited in Paul A. Cohen, History in Three Keys: Boxers as Event, Experience, and Myth (New York 1997 p49

5. Paul A. Cohen, History in Three Keys: Boxers as Event, Experience, and Myth (New York 1997 pp49-52

6. See The Yi Ho Tuan Movement of 1900 (Peking, 1976)

7 Sabine Dabringhaus, 'An Army on Vacation? The German War in China, 1900-1901', Anticipation Total War; The German and American Experiences, 1871-1914 ed. Manfred Boemeke, Roger Chickering & Stig Forster (Cambridge 1999) p475

8 Ogren, 'Conflict of sufferings,' p83, cited in Paul A. Cohen, History in Three Keys: Boxers as Event, Experience, and Myth (New York 1997 p177

9 Paul A. Cohen, History in Three Keys: Boxers as Event, Experience, and Myth (New York 1997 p55-60

10 L.R.Merchant (ed) The Siege of the Peking Legations, A diary of Lancelot Giles (1970) p148, cited in Colin Mackerras, Western Images of China (Honk Kong, 1989) p70

11 After this skirmish near Tianjin, the Yihetuan left more than 300 dead, while the allied troops suffered only 11 wounded. Kolnische Zeitung, Aug 25 1900 cited in Sabine Dabringhaus, 'An Army on Vacation? The German War in China, 1900-1901', Anticipation Total War; The German and American Experiences, 1871-1914 ed. Manfred Boemeke, Roger Chickering & Stig Forster (Cambridge 1999) p465

12 Sabine Dabringhaus, 'An Army on Vacation? The German War in China, 1900-1901', Anticipation Total War; The German and American Experiences, 1871-1914 ed. Manfred Boemeke, Roger Chickering & Stig Forster (Cambridge 1999) p463

13 Li, Lin and Lin, Yihetuan Yundong, p459 cited in Sabine Dabringhaus, 'An Army on Vacation? The German War in China, 1900-1901', Anticipation Total War; The German and American Experiences, 1871-1914 ed. Manfred Boemeke, Roger Chickering & Stig Forster (Cambridge 1999) p 464

14 For Kaiser Wilhelm's speeches see Ernst Johann (ed.), Reden des Kaiser: Ansprachen, Predigten und Trinkspruche Wilhelms II (Munich 1996) pp86-88. Translated by Richard S. Levy.

15 Kolnische Zeitung, Oct 4 1900. Sabine Dabringhaus, 'An Army on Vacation? The German War in China, 1900-1901', Anticipation Total War; The German and American Experiences, 1871-1914 ed. Manfred Boemeke, Roger Chickering & Stig Forster (Cambridge 1999) p471. The Author continues by saying that come Chinese took their own life rather than be subjected to this 'defensive act' which included rape, looting and murder.

16 Sabine Dabringhaus, 'An Army on Vacation? The German War in China, 1900-1901', Anticipation Total War; The German and American Experiences, 1871-1914 ed. Manfred Boemeke, Roger Chickering & Stig Forster (Cambridge 1999) p462

Lancelot was author of many of the photographs in the Giles Pickford collection,

Ref: Australian National University https://digitalcollections.anu.edu.au/handle/1885/20

There is a new book out on Lancelot Giles. It is called "The Siege That Never Was - Beijing 1900" by military historian Kevin Baker of the Australia Defence Force Academy. The ISBN is 978-0-9806191- 4-0

It can be ordered from:

Military Press International

PO Box 128

Yass NSW 2625

Australia

Phone (61 2) 6226 2724

e-mail milrespress@ gmail.com <mailto:milrespress@gmail.com>

http://whitecrossbo oksaustralia. com <http://whitecrossbooksaustralia.com/

Other Records Other Records

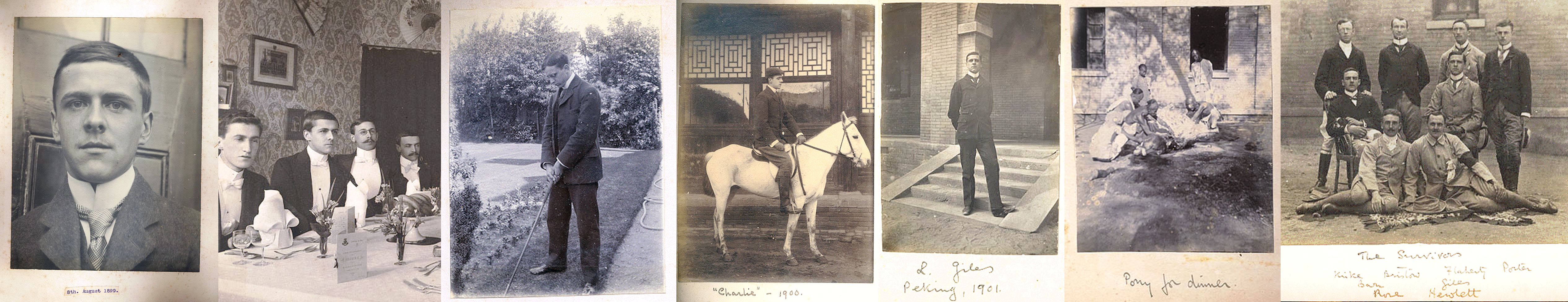

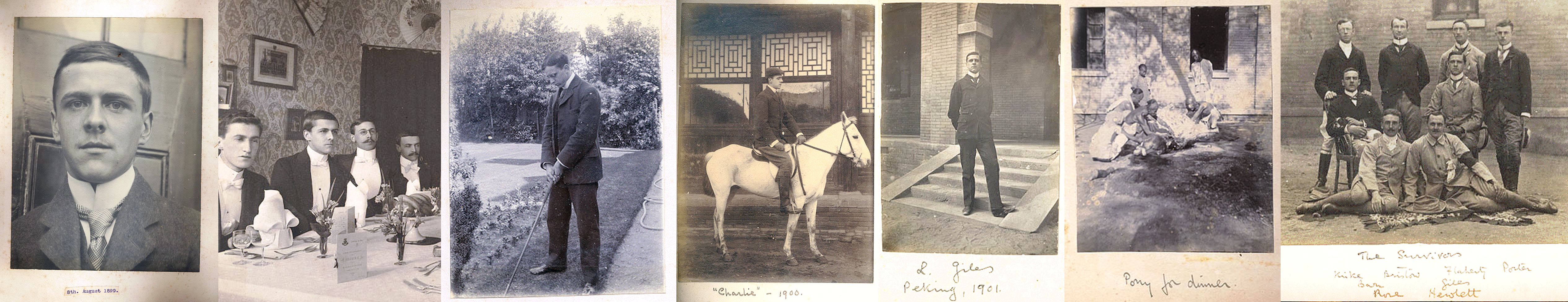

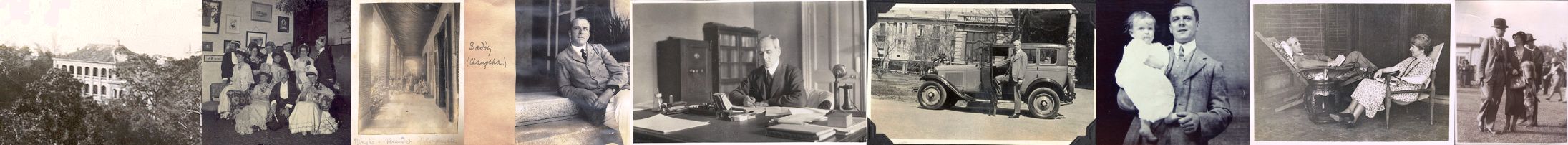

1. Lancelot Giles: His early life.

Early days as a graduate, Cambridge dinner, golf at Selwyn Gdns CAM, mounted on Charlie, on steps in Beijing, butchering a horse for food during the Defense of the Legations late 1900 - Boxer Uprising, some of the survivors from the seige.

Courtesy Giles Pickford collection, Australian National University

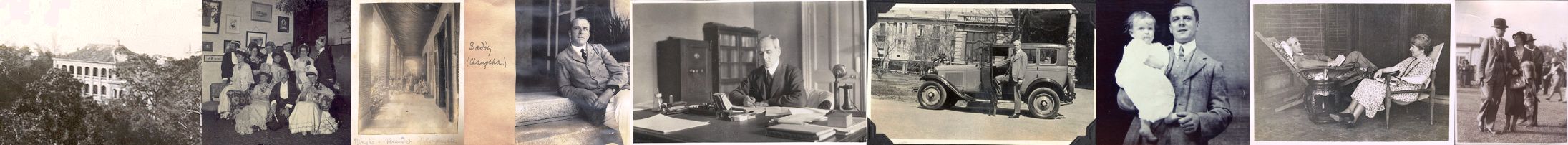

2. Lancelot Giles: Life in British Foreign Service China.

Embassy Swatow (Shantou), New Years Eve 1903 at Sir Pelham Warren's home Shanghai - https://sikhsinshanghai.wordpress.com/2013/03/02/1903-christmas-sir-pelham-warrens-place/ , Consulate Verandah Ningpo (Ningbo), Lancelot at Changsha Hunan c1920, in his office and "Our Pontiac" Lancelot's car - Tientsin 1930. With his daughter Marjory, Lancelot & Marjory, with wife and daughter Marjory.

Courtesy Giles Pickford collection, Australian National University

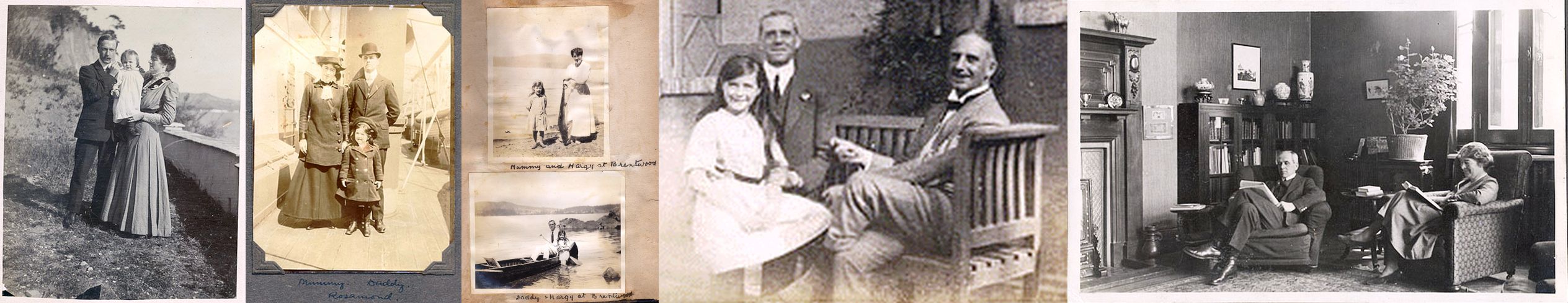

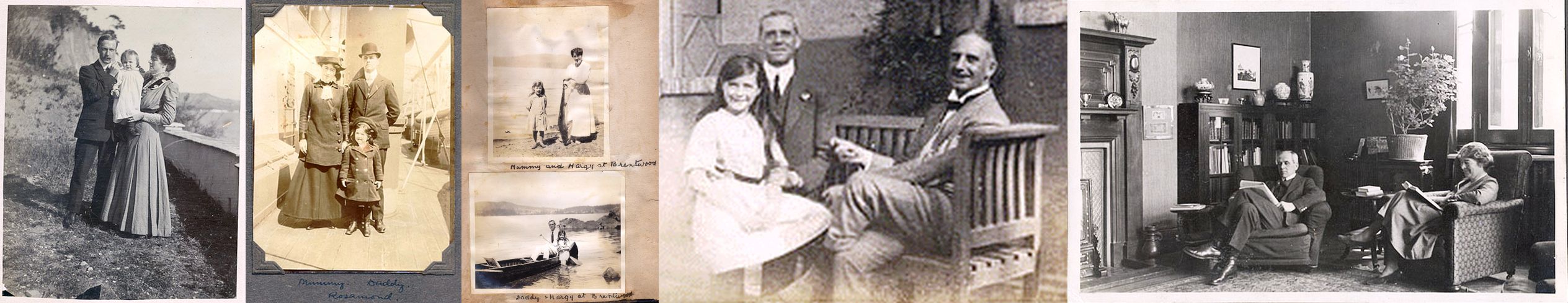

3. Lancelot Giles & family.

With Rosamond 1909, with Rosamond onboard ship, At Brentwood, with daughter Marjory & Uncle Archie, in retirement.

Courtesy Giles Pickford collection, Australian National University

Lancelot married Marjory SCOTT [411] [MRIN: 209], daughter of Dr Robert Pickett SCOTT [7492] and Amy ARNOLD [8948], on 28 Oct 1905 in St Mary Abbotts Kensington LND. (Marjory SCOTT [411] was born on 10 Jun 1888 in Hull, East Riding Yorkshire and died in 1968 in Albany Western Australia.)

|

General Notes:

General Notes: