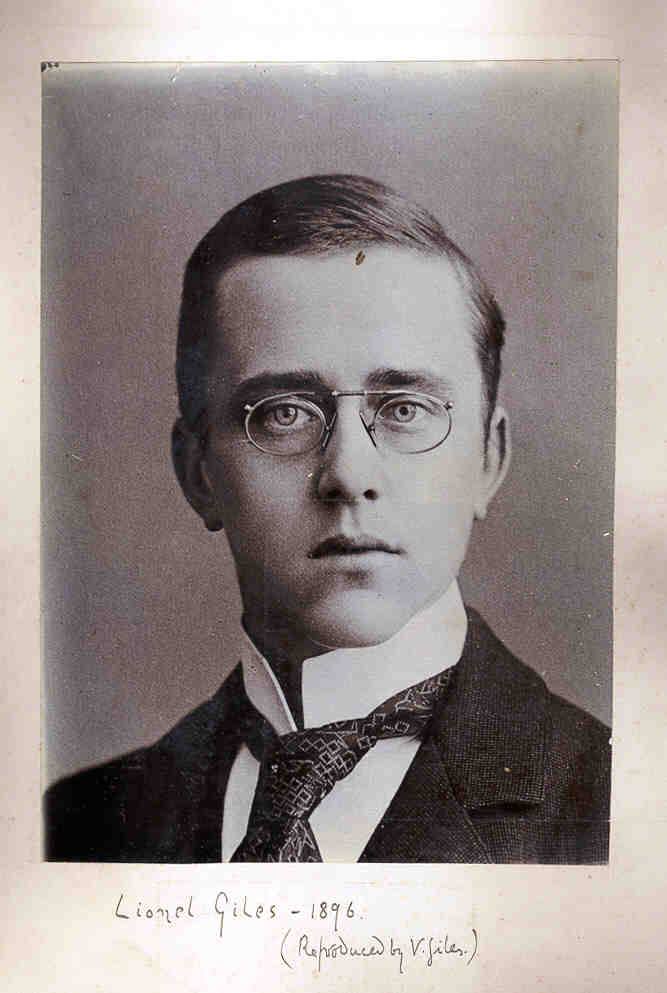

Dr Lionel GILES C.B.E [477]

- Born: 29 Dec 1875, Sutton SRY

- Marriage (1): Phyllis Isabell COUGHTRIE [2044] on 22 Oct 1903 in St Mathew West Kensington MDX

- Died: 22 Jan 1958, Langley HRT aged 82

General Notes: General Notes:

Lionel was educated at Liege Belgium, Feldkirch Austria, Aberdeen before gaining a first in Classical Mods 1897 second in Greats 1899, at Wadham Oxford. Keeper of oriental printed books and manuscripts British Museum. Translated and published many important works. Had issue a son and daughter. Died aged 82. Obituary Alstonania.

John Allen Giles Diary and Memoirs.

Page 591

October 26 Wednesday. My 73rd birthday, letter from Lionel, Herbert's boy.

Dear Granpa

I wish you many happy returns of the day. Yesterday we went up the monument; and there were 345 stairs, and there was a balcony, and when we looked down the grown-up people looked like boys. Then we got in a steamboat and went down the river tems and when we came to a bridge the funnel bent down and a lady went farther and farther, but when she found that it didnt knock her she looked at Val and laughed.

From Lionel.

Page 605

Tuesday, October 30, 1833

Anna, Lionel, and I went strait to Burnham . . . . .

J.A.G.

About 1934 Lionel visited the Hopkins family in Devises, Edward Hopkins Jnr. remembers showing him around Stonehenge and was given a 10/- note for his trouble - 2004.

This extract may indicate a philosophical point of difference, and friction between Herbert Giles the singleminded agnostic, and his son Lionel.

ANCIENT LANDMARKS:

"Nearly all the Taoist writers are fond of parables and allegorical tales, but in none of them is this branch of literature brought to such perfection as in Lieh Tzu," writes Lionel Giles to whom we owe a debt; for, unlike his father, Herbert Giles, to him Lieh Tzu is a living authority and not a myth created by Chwang Tzu. There has been a dispute as to the very existence of Lieh Tzu; but sinologists of today are more inclined to regard Lieh Tzu as an actual eminent teacher than those of a former generation; to the Chinese mind his existence was never a matter of grave doubt.

Ref: http://www.wisdomworld.org/additional/ancientlandmarks/LiehTzu.html

1939 Register

38 Abbots Road , Watford R.D., Hertfordshire, England

Lionel Giles 29 Dec 1875 Married Civil Servant Keeper Of Oriental Books & M S S British Museum

Lionel was appointed C.B.E. in 1951, by George VI.

Lionel's pen included the Sayings of Confuscious, Musings of a Chinese Mystic, also

China Society, Six Centuries at Tunhuang (Dunhuang) 1944, based on an explanatory lecture delivered 14 October 1941.

See the "Books" section of this Website1

A short account of the Stein Collection of Chinese MSS in the British Museum.

1. Edward L Fenn the collator, is a 1st Cousin (one generation removed) of Lionel Giles, he has a copy of this publication, now on this website under the "books" button.

In 2007 he visited the magnificent Mogao Caves, Dunhuang in the Hexi Corridor Gansu on the Northern Silk Road China.)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mogao_Caves

https://www.e-dunhuang.com/

https://blogs.getty.edu/iris/14-facts-cave-temples-dunhuang/

THE TIMES 27 January 1958

OBITUARY

DR. LIONEL GILES AN AUTHORITY ON CHINESE

Dr. Lionel Giles, C.B.E., a distinguished authority on Chinese, who was for 40 years on the staff of the British Museum, where he eventually became Keeper of Oriental Printed Books and Manuscripts, died on January 22. He also served as Examiner in Chinese the University of London. He was 82.

Lionel Giles was born at Sutton, Surrey, on December 29, 1875. He was the son, of H. A. Giles, Professor of Chinese at Cambridge, with whom in 1910 he collaborated in an article on the Chinese language for the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

He was educated at Liege, in Austrian Tirol, at the University of Aberdeen, and at Wadham College, Oxford, taking a first in Classical Mods in 1897 and a second class in Greats in 1899.

In 1900 he entered the British Museum, becoming an assistant in the Department of Oriental Printed Books and Manuscripts, of which in 1925 he was appointed Deputy Keeper, and in 1936 Keeper, a post which he resigned on reaching the age limit in 1940. Between 1904 and 1947 he published many important works, among which maybe mentioned especially, his translation of Sun Tzú's treatise on the Art of War in 1910; his alphabetical index to the Chinese Encyclopaedia - a massive and valuable piece of work which was printed for the Trustees of the British Museum in 1911; and Dated Chinese MSS. in the Aurel Stein Collection, 1935-43.

In 1944 a short account of the same collection, from Giles pen, was issued by the China Society under the title Six Centuries in Tunhuang.

He was appointed CBE in 1951. In 1903 Giles married Phyllis Isabel, daughter of the late James B. Coughtrie, of Hong Kong. They had a son and a daughter.

The Times 30 January 1958 pg 10 col E.

Dr Lionel Giles

Mr Henry McAleavy writes:

The own obituary notice of Dr Lionel Giles omitted to mention the most important of his many contributions to Chinese scholarship. This was his descriptive catalogue of the Chinese manuscripts from Tunhuang (Dunhuang) in the British museum. It was the result of 40 years work and was published last December.

Giles was always anxious that his own interest in China should be shared by as many people as possible. He was the last survivor of the founders of the China Society and for half a century he took a leading part in all the society's activities.

Research Notes: Research Notes:

Like his father Dr Lionel Giles was a renowned Sinologist, his English translation of Sun Tzu (The Art of War) remains the standard by which all other translations are measured.

SUN TZU ON THE ART OF WAR

THE OLDEST MILITARY TREATISE IN THE WORLD

Translated from the Chinese

By LIONEL GILES, M.A. (1910)

www.chinapage.com/sunzi-e.html

Lionel Giles lived in China for many years under the service Great Britain.

CHINA HERITAGE QUARTERLY

China Heritage Project, The Australian National University

ISSN 1833-8461

No. 13, March 2008

ARTICLES

Lionel Giles: Sinology, Old and New

John Minford

Lionel Giles' translation of The Art of War, now almost a hundred years old, has stood the test of time very well. Lionel, like his more famous father Herbert (1845-1935), was a fine Sinologist of the old school. He was born on the 29 December 1875, at Sutton in Surrey, where his grandfather was Rector of the local church.[1] He was his father's fourth son by his first wife Catherine Fenn (the first two sons died in China in infancy), and died on 22 January 1958. He was educated privately in Belgium (Liège), Austria (Feldkirch), and Aberdeen,[2] and subsequently completed his education at Wadham College, Oxford University, where he studied Classics, obtaining his BA in 1899 (First Class Honours in Mods, Second Class in Greats). Lionel seems to have been a self-effacing individual. It is interesting to note that Herbert Giles, in his Memoirs, confesses that his son Lionel acted as a 'devil' for him in writing the substantial 1910 China entries for the new edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica.[3] His willingness to be a 'backroom boy', to work quietly for others, seems to have characterised Lionel's life as a scholar.

During almost his entire professional career, he worked in the British Museum (which then incorporated what is now the British Library), entering it in 1900, and eventually rising to become Keeper of Oriental Printed Books and Manuscripts in 1936. There he worked with such distinguished 'orientalists' as Laurence Binyon (1869-1943; worked in the Museum 1893-1933) and Arthur Waley (1889-1966; worked in the Museum 1913-1930). Lionel Giles retired officially in 1940, but continued to work informally in the Museum until a few years before his death. Unjustly neglected by today's students of China, he represents an era of Sinology when a scrupulous respect for and familiarity with ancient texts was combined with a broad reading in several European languages, engagement with major intellectual issues and trends of the day, and a fluent English prose style. He produced a series of translations for the general reader of some of the great classics of Chinese philosophy The Sayings of Lao Tzu (1904), Musings of a Chinese Mystic: Selections from the Philosophy of Chuang Tzu [selected and adapted from Herbert Giles' version] (1906), The Sayings of Confucius (1907), Taoist Teachings from the Book of Lieh Tzu (1912), The Book of Mencius (1942), A Gallery of Chinese Immortals (1948) all titles published in John Murray's excellent Wisdom of the East series, edited by Cranmer-Byng father and son. He also published a vast number of scholarly articles and shorter translations (many in the pages of the Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, or T'oung Pao), and several valuable bibliographical studies including An Alphabetical Index to the Chinese Encyclopedia, which he finished in 1911 (the year after his Art of War translation). He quietly helped many other workers in the field, as when he undertook the huge task of proofreading W. E. Soothill (1861-1935) and Lewis Hodous's (b.1872) Dictionary of Chinese Buddhist Terms.[4] Soothill, who was Professor of Chinese at Oxford, in his Preface dated 1934, gave thanks, hailing Lionel as the 'illustrious son of an illustrious parent', and referring to his 'ripe scholarship and experienced judgement'. Soothill died shortly after writing the preface. Three years later (1937), his collaborator Hodous wrote a Preface, from Hartford, Connecticut, praising Lionel's work in glowing terms: 'Dr Giles ... has had to assume a responsibility quite unexpected by himself and by us. For two to three years, with unfailing courtesy and patience, he has considered and corrected the very trying pages of the proofs, while the Dictionary was being printed. He gave chivalrously of his long knowledge both of Buddhism and of the Chinese literary characters.'

In 1951, Lionel Giles was honoured by King George VI who made him a C.B.E. 'in recognition of his services to Sinology' a most appropriate citation. In a fine obituary, printed in the Hong Kong University Journal of Oriental Studies in 1960, J. L. Cranmer-Byng writes of his friend as a 'slight figure, a mild looking man with a rapt expression... Giles once confessed to me that he was a Taoist at heart, and I can well believe it, since he was fond of a quiet life, and was free of that extreme form of combative scholarship which seems to be the hall mark of most Sinologists.' He was 'particularly fond of his home, The Knoll, in the village of Abbot's Langley near Watford. Here in summer weather he liked to sit in his small but well-grown garden and chat with a congenial friend or two.' He was apparently a methodical and neat man. His manuscript of A Gallery of Chinese Immortals was 'beautifully written in a neat hand with the footnotes added in red ink.' Cranmer-Byng also alludes to Lionel Giles' important role as Secretary of the China Society (he took this on in 1911).

Lionel Giles wrote countless excellent book reviews for the Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. He was capable of being most generous in his appraisal of others (more so than his father). Of Lin Yutang's The Wisdom of China he wrote: 'Brilliant and versatile as ever, he is able to give us a better insight into the hearts of his countrymen than any other writer.'[5] On the subject of Pearl Buck's version of the novel Shuihuzhuan, he wrote: 'One feels that the author of The Good Earth, with her broad and tolerant outlook on life, was the predestined translator of this work [All Men Are Brothers], instinct as it is with a warm, comprehensive humanity.'[6] But he could also be severely, if politely, critical, as in his review of E. R. Hughes' Chinese Philosophy in Classical Times: 'Though his fluency never deserts him, one cannot help feeling that it is being used not so much to fill the gaps in our knowledge as to conceal the deficiencies in his... We begin to wonder if the writer is fully competent to undertake a piece of work involving so much translation from the Chinese...'[7] In a lengthy review of Arthur Waley's Catalogue of Paintings Recovered from Tun-huang, he begins by singing his Museum colleague's praises: 'It is ... fortunate that the Catalogue has been prepared by a scholar of the calibre of Mr. Waley. Indeed, it is hardly too much to say that he is the one man in this country who combines sufficient knowledge of Buddhism, Oriental art, and the Chinese language to undertake such a task.' But Giles goes on to devote fourteen pages to a list of polite but precise, fearless and judicious corrections, on occasions including the eminent French Sinologue Pelliot: 'Both Mr Waley and Professor Pelliot are wrong here...'[8] Contrast this with the earlier heated exchange in the pages of the New China Review between Waley and Giles père on the subject of translating Chinese poetry.[9]

From time to time, Lionel used the occasion of a book review to put forward a well-considered argument on some general matter, as when writing about Xiao Qian's Etchings of a Tormented Age: 'He begins by telling how the collapse of the Manchu Empire led to a further revolution in the world of letters, in which the plain vernacular was universally adopted in place of the age-hallowed classical style. This is putting it too strongly. Chinese as it is actually spoken is too clumsy and diffuse to be suitable for most forms of literary expression, especially poetry; and although the old allusive, carefully balanced style of composition has been generally abandoned, it cannot be said that its place has been taken by the language of the market-place. There are many gradations between these two extremes, and even in journalism some compromise has been found necessary. Admittedly some change in the direction of greater simplicity was called for; but now that the first flush of revolutionary enthusiasm is over the reformers are beginning to realize how difficult it is for a nation to cut itself off from tradition and make an entirely fresh start. Our own great innovator, Wordsworth, found it impossible in the long run to use the language of common speech consistently for poetic purposes, and it may reasonably be doubted whether poems will ever be written in the vernacular to compare with those of the great T'ang masters. All the more must our sympathy go out to those ardent spirits who are struggling to solve so complex a problem, in order that Chinese literature may continue to prove not unworthy of its glorious past.'[10]

He was sometimes highly critical of the missionary bias of the previous generation of translators, as in the Introduction to his own Analects, where he takes James Legge and others to task: 'The truth is, though missionaries and other zealots have long attempted to obscure the fact, that the moral teaching of Confucius is absolutely the purest and least open to the charge of selfishness of any in the world.' He goes on to claim: 'Confucianism really represents a more advanced stage of civilisation than biblical Christianity... His whole system is based on nothing more nor less than the knowledge of human nature.'[11]

As a critic of translation, he could be firm: 'M. Margouliès has a nice appreciation of Chinese literary composition which is remarkable in a foreigner; he can savour the fine points of style that distinguish authors of different dynasties and different schools; yet apparently he cannot see that a rigidly literal translation of these same authors must almost necessarily obliterate the style which is of their very essence, and reduce them all to a dead level devoid of inspiration... [And yet] good French prose, with its grace, flexibility and lightness of touch, is precisely the medium which would appear best suited for the rendering of ku-wen.'[12] Lionel proceeds to compares the French version unfavourably with his father's versions in Gems of Chinese Literature.[13]

During his long tenure at the British Museum, Lionel Giles worked on an exhaustive catalogue of the priceless collection of some seven thousand manuscripts dating between c.400 and 1000CE, which the explorer Aurel Stein had brought back from the oasis of Dunhuang after 1907. This life's work of his finally bore fruit in 1957, a year before his death, with the publication of the magnificently produced and impeccably researched descriptive Catalogue of the Chinese Manuscripts from Tunhuang in the British Museum (xxv + 333 pp).[14] 85% of the manuscripts were of Buddhist texts, 3% Taoist, 12% secular or non-religious. 'It was no light task', he wrote in 1941, 'even in a physical sense, for the total length of the sheets which had constantly to be unrolled and rolled up again must have amounted to something between ten and twenty miles.' A simpler introduction to the subject is provided in his booklet for the China Society, Six Centuries at Tunhuang (Dunhuang) 1944, based on a lecture delivered 14 October 1941. See the "Books" section of this Website

Lionel Giles was a fluent and elegant translator, with a wide repertoire of expressions. Take this passage from one of his earliest published works, The Sayings of Lao Tzu:

"All men are radiant with happiness, as if enjoying a great feast, as if mounted on a tower in spring. I alone am still, and give as yet no sign of joy. I am like an infant which has not yet smiled, forlorn as one who has nowhere to lay his head. Other men have plenty, while I alone seem to have lost all. I am a man foolish in heart, dull and confused. Other men are full of light; I alone seem to be in darkness. Other men are alert; I alone seem listless. I am unsettled as the ocean, drifting as though I had no stopping-place. All men have their usefulness; I alone am stupid and clownish. [15]"

One of his finest translations was an eloquent rendering of the Tang-dynasty poet Wei Zhuang's (c.836-c.910) long ballad-poem about the devastating sack of the city of Chang'an by the brigand Huang Chao in 881. Lionel's somewhat old-fashioned and restrained style as a translator enhances the relentless detail of the terror, the rape and pillage. The poem in translation reads almost like a present-day news report from a war-zone.

"Every home now runs with bubbling fountains of blood, Every place rings with a victim's shrieks \endash shrieks that cause the very earth to quake. Our western neighbour had a daughter verily, a fair maiden! Sidelong glances flashed from her large limpid eyes, And when her toilet was done, she reflected the spring in her mirror; Young in years, she knew naught of the world outside her door. A ruffian comes leaping up the steps of her abode; Pulling her robe from one bare shoulder, he attempts to do her violence, But though dragged by her clothes, she refuses to pass out of the vermilion portal, And thus with rouge and fragrant unguents she meets her death under the knife."

Like so much of his work, this translation was published in the pages of a learned journal (T'oung Pao, 1924). The poem itself had long been lost, and Giles re-discovered it among the Dunhuang materials he was working on at the Museum. His account of this 'most romantic discovery' is to be found on pages 21-23 of Six Centuries at Tunhuang. As he writes: 'Such things are brought home to us with peculiar poignancy in these days of air-raids and bombing.'[16]

The Giles translation of The Art of War was first published in 1910, by Luzac & Co., the old London Orientalist publishing house. Lionel dedicated it to his younger brother, Capt. Valentine Giles, officer in the Royal Engineers, 'in the hope that a work 2400 years old may yet contain lessons worth consideration by the soldier of today.' It is one of his most thorough and scholarly works, and unlike his various popular translations, contains not only the complete Chinese text, but also an extensive and excellent textual apparatus and commentary. It is quite remarkable how deeply and thoroughly Giles enters into the (often intractable) text, recognising the quality of the Chinese writing (and even identifying the occasional rhyming jingle see XII:16). In some ways, and surprisingly, this is a superior Sinological achievement to anything by his father, H. A. Giles, the great Cambridge Professor. The care with which Lionel reads, translates and sometimes synthesises the often rambling and contradictory commentaries, is remarkable. On top of all of this, he enlivens the book with many stimulating, sometimes controversial editorial asides, references to episodes in western history, to Maréchal Turenne (1611-1675), Napoleon, Wellington, the Confederate General 'Stonewall' Jackson (1824-1863) and Baden-Powell (1857-1941) and his Aids to Scouting. Giles (like Professor Li Ling today at Peking University) was constantly on the look out for contemporary resonances ('lessons worthy of consideration'), as when he saw the link between Sunzi's thinking and the development of 'scouting' as a branch of army training. It is also worth remembering the historical and personal context in which he was translating: a mere ten years earlier, the Boxer Uprising was at its height and the Western legations in Peking were under siege; one of Lionel's other brothers, Lancelot, was serving as a young Student Interpreter in Peking, where he was decorated for gallantry in the defence of the Legation.[17] In Chapter XI, section 13, Lionel comments that the commentators' injunction not to rape and loot 'may well cause us to blush for the Christian armies that entered Peking in 1900 AD.'

With this new edition, readers of The Art of War are in safe hands. They are presented with a reliable and readable translation from a seasoned reader of literary Chinese, and (most importantly) as they read they are able to consult in English a rich selection of traditional Chinese readings and commentaries. Together these form a sound basis on which the reader can reach conclusions, as opposed to the ready-made (and often unquestioning) interpretations and instructions that tend to emerge from the numerous more recent versions.

Some of us today are striving to bring back into Chinese Studies something of the depth (and excitement) of the best early Sinology, to create a New Sinology, that transcends the narrow concerns of the prevalent Social Sciences-based model.[18] We recognise (as did Lionel Giles) the urgency of applying the past to the present, the pressing need to understand today's China, as the world's rising power. In so doing, we are deeply aware of the need to understand the historical roots of China's contemporary consciousness. For these purposes, this work is a model study, scholarly but at the same time alive both to enduring humanistic concerns and to concrete present-day issues. It exemplifies ideals similar to those announced by Lionel's contemporary, the great humanist, scholar, translator and promoter of the League of Nations, Gilbert Murray,[18] when he wrote in 1918:

The scholar's special duty is to turn the written signs in which old poetry or philosophy is now enshrined back into living thought or feeling. He must so understand as to re-live.'[19]

To go a little further back in time, Giles' work continues the grand tradition of Thomas Arnold, father of Mathew, and reforming headmaster of Rugby School, of whom Rex Warner wrote:

When he [Arnold] spoke of Thucydides or Livy his mind was directed to the present as well as the past... In his hands education became deliberately 'education for life.'[20]

These are the very goals, this is the very breadth, to which the New Sinology also aspires. And this little classic, so old, and yet so relevant and popular today, is an ideal text for the purpose. Which brings us to the next fundamental tenet. To read this book in the original, one needs to know literary (or classical) Chinese now rarely taught in the world's universities. This basic ability, some degree of familiarity with the literary language in which the majority of China's heritage is expressed, is essential for anyone professing to 'understand' China. David Hawkes made the point eloquently in his Inaugural Lecture at Oxford [see the December 2007 issue of China Heritage Quarterly Ed.]:

To lack either one of these two languages [the Classical and the Colloquial] would not be a mere closing of certain doors; it would cripple the researcher and render his labours nugatory... Just as the study of Colloquial literature constantly involves the student in reading memoirs, biographies, commentaries, and criticisms in Classical Chinese, so the study of Chinese antiquity necessitates his perusal of learned works by modern Chinese scholars written in the Colloquial language...

For Hawkes, this insistence on a broad literacy in both kinds of Chinese (since they are so inextricably interwoven) is but part of a broader vision:

The study of Chinese is not merely the study of a foreign language. It is the study of another culture, another world 'une autre Europe au bout de l'Asie' Michelet called it.[21] To go into this storehouse of dazzling riches and select from among the resplendent vessels of massive gold one small brass ashtray made in Birmingham \endash this would be to show a want of imagination, a lack of love, that would unfit us for university teaching of any kind.[22]

To return to the book in hand: to read The Art of War at all intelligently in translation, one needs to be familiar with its historical and philosophical context. And then its contemporary relevance becomes even clearer and even greater. Lionel Giles succeeds in providing the essential materials for this sort of informed reading. There exists no better representation of the old tradition of Sinology at its most typical and at its best.

Giles occasionally made errors of judgement. For example, he misjudged the early French translation of Amiot, which he deemed 'little better than an imposture'. In fact Amiot was working (as did many Jesuits) from a Manchu paraphrase of the eighteenth century, which makes his 'free' and discursive version all the more interesting. Giles' recurring and often ill-tempered broadsides against the unfortunate Captain Calthrop and his flawed 1908 translation (he almost seems to have been emulating his notoriously irascible and often petulant father) are the only feature that mars and dates an otherwise splendid book. This defect is not to be found in his other writings.

From John Minford,

'Foreword' to a new edition of Sunzi: The Art of War translated by Lionel Giles, forthcoming, Vermont: Tuttle, 2008.

Notes:

1. Much of the family information is to be found in Aegidiana, or Gleanings Among the Gileses, printed for private circulation in 1910. I am much indebted to Giles Pickford, Lionel Giles' great-nephew, for pointing me in this direction, and to Darrell Dorrington for his help in locating this fascinating family chronicle. They were also both instrumental in allowing and facilitating the reproduction of the photograph of Lionel used as a frontispiece to this book.

2. As were all the other surviving sons Bertram, Valentine and Lancelot. Both Bertram (born 1874) and Lancelot (born 1878) entered the British China Consular Service, following in their father's footsteps. Valentine became a soldier and joined the Royal Engineers.

3. Charles Aylmer, 'The Memoirs of H. A. Giles', East Asian History, 13/14 (June/December 1997), pp.51-2.

4. Soothill, William Edward, and Lewis Hodous, A Dictionary of Chinese Buddhist Terms, with Sanskrit and English equivalents and a Sanskrit-Pali index (London, 1937).

5. BSOAS 13, 3 (1950), p.798.

6. BSOAS 7, 13 (1934), p.631.

7. BSOAS 11, 1 (1943), p.236.

8. BSOAS 7, 1 (1933), pp.179-92.

9. See, for example, Giles' 'A Re-Translation', in New China Review, 2 (1920), pp.319-40, and 'Mr Waley and "The Lute Girl's Song"' in NCR, 3 (1921), pp.423-28.

10. BSOAS 11, 1 (1943), pp.238-9.

11. The Sayings of Confucius: A New Translation of the Greater Part of the Confucian Analects, with Introduction and Notes by Lionel Giles (London, 1907), pp.26-8.

12. Review of Margouliès, Le Kou-wen Chinois, in BSOAS, 4, 3 (1927), pp.640-643.

13. Herbert A. Giles, Gems of Chinese Literature: Prose, second edition, Shanghai and London, 1922.

14. 'He devoted the greater part of his available time and energy to studying the manuscripts, continuing this work as his health permitted after his retirement.' E. G. Pulleyblank, BSOAS, 22, 2, p.409.

15. The Sayings of Lao Tzu, translated from the Chinese, with an Introduction, by Lionel Giles, Assistant at the British Museum, London, 1904, p.54.

16. His translation has recently been reprinted in a more widely read anthology. See Minford & Lau, Chinese Classical Literature: An Anthology of Translations, New York, 2000, pp.933-944.

17. See Lancelot Giles, The siege of the Peking legations: a diary, edited with introduction: 'Chinese anti-foreignism and the Boxer uprising', by L.R. Marchant, foreword by Sir R. Scott, Nedlands: Western Australia, 1970.

18. I refer especially to the courageous work of my colleague Geremie Barmé, who together with others has over the past few years begun the articulation of a New Sinology.

18. Gilbert Murray, 'Religio Grammatici: The Religion of a Man of Letters', Presidential Address to the Classical Association, 8 January 1918, collected in Humanist Essays, London, 1964. Murray was born in Sydney, Australia, in 1866, and died in 1957 at Oxford, where he had been Professor of Greek for nearly thirty years (1908-1936).

19. Rex Warner, English Public Schools, London, 1946.

20. Jules Michelet, Histoire de France, vol.VIII, 'Réforme', Paris, 1855, p.488.

21. David Hawkes, ed. Minford and Wong, Chinese: Classical, Modern and Humane, Hong Kong, 1989, pp.18-9.

The above excerpt is from a preface to a reissuing of Lionel Giles' translation of Sunzi's The Art of War. It is a timely addition to our general discussion of 'New Sinology' (see <http://rspas.anu.edu.au/pah/chinaheritageproject/newsinology/> and David Hawkes, 'Chinese: Classical, Modern and Humane', in China Heriage Quarterly, Issue 12, December 2007).

John Minford's own translation of Sunzi's text was published by Penguin Classics in 2003.-GRB.

China Heritage Project, ANU College of Asia & the Pacific (CAP), The Australian National University

Please direct all comments or suggestions to contact@chinaheritagequarterly.org.

This page last updated: October 19 2015 17:56:11.

URL: http://www.chinaheritagequarterly.org/articles.php?searchterm=013_giles.inc&issue=013

Wikipedia

Lionel Giles (29 December 1875 - 22 January 1958) was a British sinologist, writer, and philosopher. Lionel Giles served as assistant curator at the British Museum (which then incorporated what is now the British Library) and Keeper of the Department of Oriental Manuscripts and Printed Books. He is most notable for his 1910 translation of The Art of War by Sun Tzu and The Analects of Confucius.

Early life

Giles was born in Sutton, the fourth son of Herbert Giles and his first wife Catherine Fenn. Educated privately in Belgium (Liège), Austria (Feldkirch), and Scotland (Aberdeen), Giles studied Classics at Wadham College, Oxford, graduating BA in 1899.[1][2]

The Art of War

Main article: The Art of War

The 1910 Giles translation of The Art of War succeeded British officer Everard Ferguson Calthrop's[3] 1905 and 1908 translations, and refuted large portions of Calthrop's work. In the Introduction, Giles writes:

It is not merely a question of downright blunders, from which none can hope to be wholly exempt. Omissions were frequent; hard passages were willfully distorted or slurred over. Such offenses are less pardonable. They would not be tolerated in any edition of a Latin or Greek classic, and a similar standard of honesty ought to be insisted upon in translations from Chinese.[4]

Sinology

Lionel Giles used the Wade-Giles romanisation method of translation, pioneered by his father Herbert. Like many sinologists in the Victorian and Edwardian eras, he was primarily interested in Chinese literature, which was approached as a branch of classics. Victorian sinologists contributed greatly to problems of textual transmission of the classics. The following quote shows Giles' attitude to the problem identifying the authors of ancient works like the Lieh Tzu, the Chuang Tzu and the Tao Te Ching:

The extent of the actual mischief done by this "Burning of the Books" has been greatly exaggerated. Still, the mere attempt at such a holocaust gave a fine chance to the scholars of the later Han dynasty (A.D. 25-221), who seem to have enjoyed nothing so much as forging, if not the whole, at any rate portions, of the works of ancient authors. Some one even produced a treatise under the name of Lieh Tzu, a philosopher mentioned by Chuang Tzu, not seeing that the individual in question was a creation of Chuang Tzu's brain![5]

Continuing to produce translations of Chinese classics well into the later part of his life, he was quoted by John Minford as having confessed to a friend that he was a "Taoist at heart, and I can well believe it, since he was fond of a quiet life, and was free of that extreme form of combative scholarship which seems to be the hall mark of most Sinologists."[1]

Translations

The prodigious translations of Lionel Giles include the books of: Sun Tzu, Chuang Tzu, Lao Tzu, Mencius, and Confucius.

The Art of War (1910), originally published as The Art of War: The Oldest Military Treatise in the World

The Analects of Confucius (1910), also known as the Analects or The Sayings of Confucius[6]

The Sayings of Lao Tzu and Taoist Teachings (1912), now known as the Tao Te Ching[7]

The Book of Mencius (1942), originally published as Wisdom of the East[8]

The Life of Ch'iu Chin and The Lament on the Lady of the Ch'in[6]

A Gallery of Chinese Immortals (1948), excerpts from the Liexian Zhuan[9][10]

References

1. John Minford, Sinology, Old and New China Heritage Quarterly

2. Forbes, Andrew ; Henley, David (2012).'Lionel Giles' in: The Illustrated Art of War: Sun Tzu. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B00B91XX8U

3. Calthrop was killed in action in December 1915 in Flanders. "The Late Major E. F. Calthorp, R.A.F." The Spectator. 12 February 1916. Everard F. Calthorp's only sister, Hope Calthorp (1881-1960), married Lieutenant-Colonel Hermann Gaston de Watteville in 1914.

4. Lionel Giles, The Art of War by Sun Tzu - Classic Collector's Edition, ELPN Press, 2009 ISBN 1-934255-15-7

5. Lionel Giles, tr. Taoist Teachings from the Book of Lieh-Tzu. London: Wisdom of the East. 1912

6. John Minford, Classical Chinese Literature: An Anthology of Translations, Columbia University Press, 2000 ISBN 0-231-09677-1

7. Lionel Giles and Herbert Giles, Tao: The Way, ELPN Press, 2007 ISBN 1-934255-13-0

8. Meaning in The Book of Mencius Encyclopædia Britannica

9. Herbert Giles, Frederic Balfour, Lionel Giles, Biographies of Immortals: Legends of China, ELPN Press, 2010 ISBN 1-934255-30-0

10. Giles, Lionel (1948), A Gallery of Chinese Immortals, London: John Murray, ISBN 0-404-14478-0 , reprinted 1979 by AMS Press (New York).

External links

Wikisource has original works written by or about:

Lionel Giles

Works by Lionel Giles at Project Gutenberg

Works by or about Lionel Giles at Internet Archive

Works by Lionel Giles at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

Lionel Giles' Translation of the Tao Te Ching at sacred-texts

Lionel Giles' Translation from Taoist teachings from the book of Lieh Tzu at Wikisource

A Gallery of Chinese Immortals translated by Lionel Giles

West Yorkshire Archive Service, Calderdale:

Papers of the Armytage family of Kirklees Hall [KM/B/1 - KM/D/1]

Muniments of Kirklees and the Armytage Family

Catalogue Ref. KM

Creator(s):

Armytage family of Kirklees Hall, Clifton-cum-Hartshead, West Riding of Yorkshire

[Access Conditions]

Some files are subject to access conditions

KM/B

FAMILY RECORDS

PERSONAL CORRESPONDENCE AND RELATED PAPERS

Antiquarian and Historical

FILE - Chinese book - ref. KM/B/872 - date: 1841-1915

[from Scope and Content] A manual of Taoist divination (1841), with 2 red visiting cards, a letter from Lionel Giles of Dept. of Oriental Printed Books and Manuscripts of the British Museum, 1915, and a translation of 2 letters enclosed with the book.

Ref A2A

Other Records Other Records

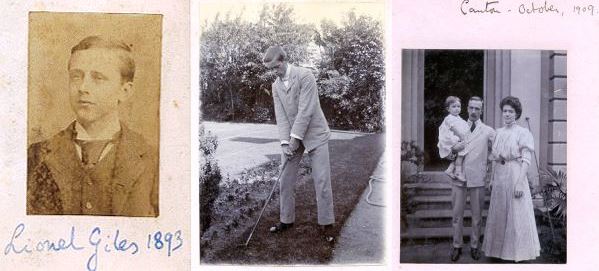

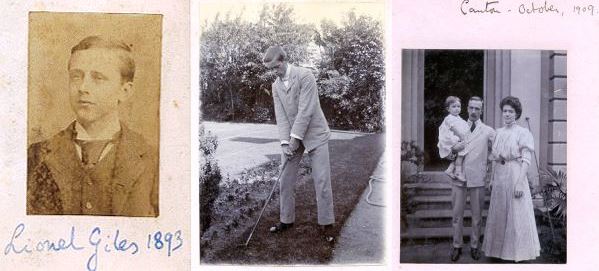

1. Lionel Giles: Various images.

As young man aged 18, 1893. Golf c1900 at Selwyn Gardens Cambridge, Canton 1909 with his sister-in-law Marjory and niece Rosamond.

2. Dr Lionel Giles: The Worlds Oldest Dated Book, 868AD, Dunhuang Hexi Corridor, Jiuquan Gansu China.

Lionel was Assistant Curator and Keeper of Oriental Printed Books and Manuscripts at the British Museum, (which then incorporated what is now the British Library) one of the greatest collections in the World.

One of the exceptional items under his care was the Diamond Sutra, the Worlds oldest book.

The images are of Aurel Stein, parts of the Diamond Sutra, and Aurel Stein against an photograph of the 9thC cave at Mogao, Dunhuang Oasis on the Northern Silk Road, China. It is decorated in Buddhist imagery and contained some 40,000 manuscripts, mainly containing early Buddhist sutras (sacred teachings), but also poetry, medical recipes, biographies etc. Stein secured a large number for the British Museum.

Giles produced a "Catalogue of the Chinese Manuscripts from Tunhuang (Dunhuang) in the British Museum", an enormous task. A simpler introduction to this subject is provided in his booklet for the China Society, "Six Centuries at Tunhuang (1944)", based on a lecture delivered 14 October 1941.

See the "Books" section of this Website

About the Diamond Sutra, the World's Oldest Dated Printed Book

Printed over 1,100 years ago, a Chinese copy of the Diamond Sutra at the British Library is one of the most intriguing documents in the world no one is sure who Wang Jie was or why he had The Diamond Sutra printed. But we do know that on this day in 868 A.D., or the 13th of the 4th moon of the 9th year of Xiantong in Jie's time he commissioned a block printer to create a 17½ foot long scroll of the sacred Buddhist text, including an inscription on the lower right hand side reading, "Reverently made for universal free distribution by Wang Jie on behalf of his two parents." Today, that scroll is housed at the British Library and is acknowledged as the oldest dated printed book in existence.

The Gutenberg Bible, the first book made with moveable type, came along almost 600 years later. Bibliophiles might also have a working knowledge of other famous manuscripts like the Book of Kells, The Domesday Book, and Shakespeare's First Folio., The Diamond Sutra should be in that pantheon of revered books, as well. Here's why:

Origins

The text was originally discovered in 1900 by a monk in Dunhuang, China, an old outpost of the Silk Road on the edge of the Gobi Desert. The Diamond Sutra, a Sanskrit text translated into Chinese, was one of 40,000 scrolls and documents hidden in "The Cave of a Thousand Buddhas," a secret library sealed up around the year 1,000 when the area was threatened by a neighboring kingdom.

In 1907, British-Hungarian archaeologist Marc Aurel Stein was on an expedition mapping the ancient Silk Road when he heard about the secret library. He bribed the abbot of the monastic group in charge of the cave and smuggled away thousands of documents, including The Diamond Sutra.

The International Dunhuang Project is now digitizing those documents and 100,000 others found on the eastern Silk Road.

Content.

The Diamond Sutra is relatively short, only 6,000 words and is part of a larger canon of "sutras" or sacred texts in Mahayana Buddhism, the branch of Buddhism most common in China, Japan, Korea and southeast Asia. Many practitioners believe that the Mahayana Sutras were dictated directly by the Buddha, and The Diamond Sutra takes the form of a conversation between the Buddha's pupil Subhati and his master.

A full translation of the document's title is The Diamond That Cuts Through Illusion. As Susan Whitfield, director of the Dunhuang Project explains, the sutra helps cut through our perceptions of the world and its illusion. "We just think we exist as individuals but we don't, in fact, we're in a state of complete non-duality: there are no individuals, no sentient beings," Whitfield writes.

Why did Wang Jie commission it ?

According to Whitfield, in Buddhist belief, copying images or the words of the Buddha was a good deed and way of gaining merit in Jie's culture. It's likely that monks would have unrolled the scroll and chanted the sutra out loud on a regular basis. That's one reason printing developed early on in China, Whitfield explains. "If you can print multiple copies, and the more copies you're sending out, the more you're disseminating the word of Buddha, and so the more merit you are sending out into the world," she writes. "And so the Buddhists were very quick to recognize the use of the new technology of printing."

What is one quote I should know from The Diamond Sutra?

It's difficult to translate the sutra word for word and still catch its meaning. But this passage about life, which Bill Porter, who goes by the alias "Red Pine," adapted to English, is one of the most popular:

So you should view this fleeting world

A star at dawn, a bubble in a stream,

A flash of lightening in a summer cloud,

A flickering lamp, a phantom, and a dream.

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/Five-things-to-know-about-diamond-sutra-worlds-oldest-dated-printed-book-180959052/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mogao_Caves

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diamond_Sutra

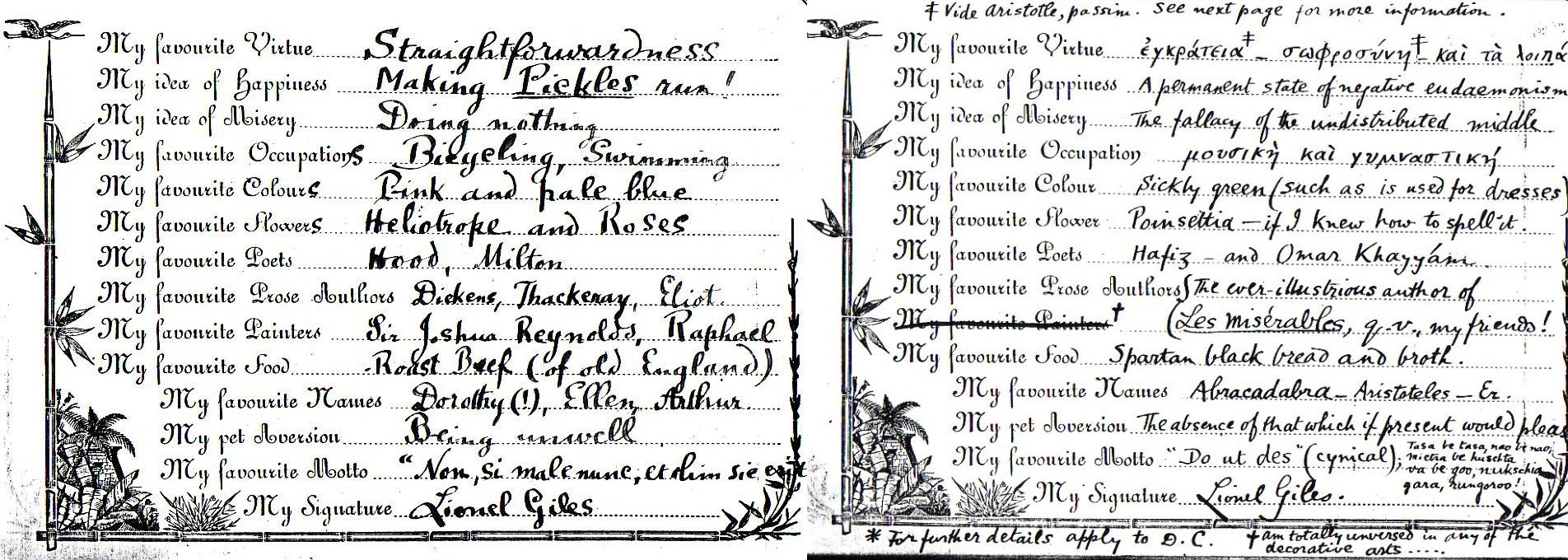

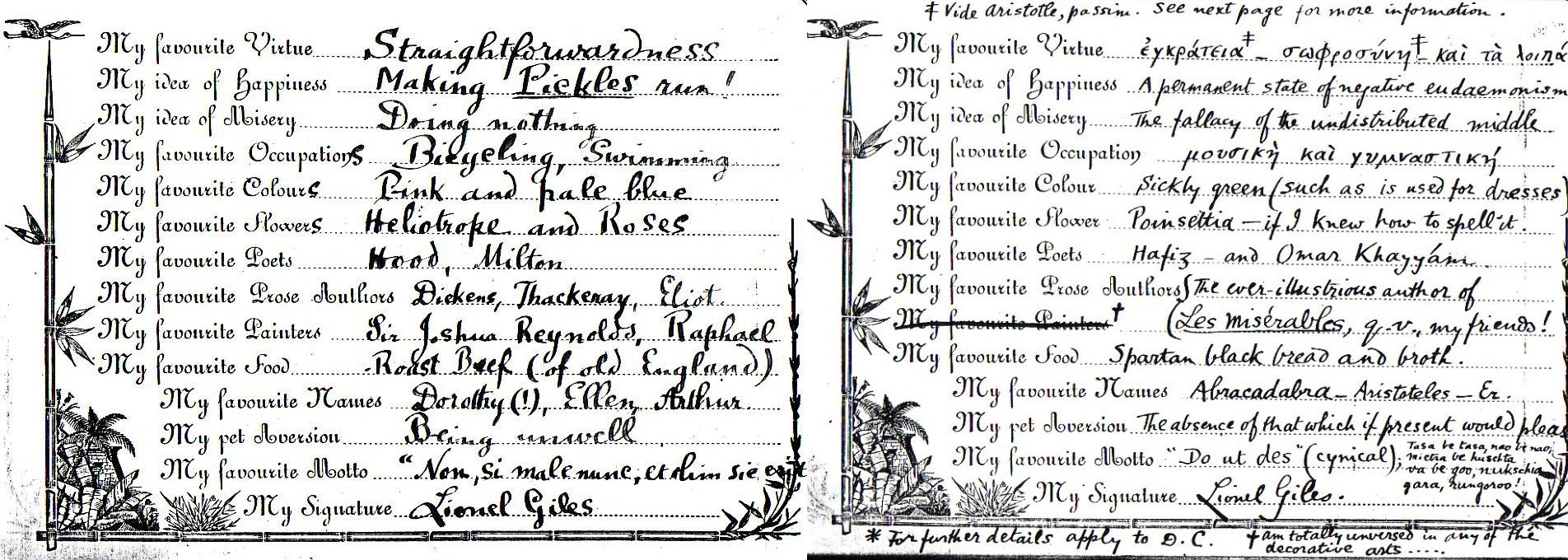

3. Lionel Giles: Lionel made two confessions to his pretty cousin Dolly Cotes [486], 1891.

LIONEL'S CONFESSIONS 1891

MY FAVOURITE VIRTUE: Straightforwardness

MY IDEA OF HAPPINESS: Making Pickles* run

MY IDEA OF MISERY: Doing nothing

MY FAVOURITE OCCUPATION: Bicycling Swimming

MY FAVOURITE COLOUR: Pink & pale blue

MY FAVOURITE FLOWER: Heliotrope & roses

MY FAVOURITE POETS: Hood Milton

MY FAVOURITE PROSE AUTHORS: Dickens Thackeray Eliot

MY FAVOURITE PAINTER: Sir Joshua Reynolds, Raphael

MY FAVOURITE FOOD: Roast beef (of old England)

MY FAVOURITE NAMES: Dorothy (!) Ellen Arthur

MY PET AVERSION: Being unwell

MY FAVOURITE MOTTO:"Non Si male nunc et him sie exit"

(* Pickles was the Fenn's dog)

LIONEL'S CONFESSIONS 1898

MY FAVOURITE VIRTUE: Entry in Greek !

MY IDEA OF HAPPINESS: A permanent state of negative endaemonism

MY IDEA OF MISERY: The fallacy of the undistributed middle

MY FAVOURITE OCCUPATION: More Greek !

MY FAVOURITE COLOUR: Sickly green (such as is used for dresses)

MY FAVOURITE FLOWER: Poinsettia - if I knew how to spell it

MY FAVOURITE POETS: Hafiz & Omar Khayyam

MY FAVOURITE PROSE AUTHORS: The ever illustrious author of Les Miserables q.v my friends.

MY FAVOURITE PAINTER: Am totally unversed in any of the decorative arts

MY FAVOURITE FOOD: Spartan black bread & broth

MY FAVOURITE NAMES: Abracadabra, Aristoteles, Er

MY PET AVERSION: The absence of that which if present would please

MY FAVOURITE MOTTO: "Do ut des" (cynical). Tasa be tasa, nao be nao, Mietra be huselta va be goo nukschia gara nungoroo!

4. Census: England, 31 Mar 1901, Selwyn Gardens Cambridge. Lionel is recorded as a son single aged 25 British Museum born Sutton SRY

5. Census: England, 2 Apr 1911, 13 Whitehall Gardens Acton Hill MDX. Lionel is recorded as Head of a seven room house aged 35 married an assistant at the British Museum born Sutton SRY

Lionel married Phyllis Isabell COUGHTRIE [2044] [MRIN: 664], daughter of James Billington COUGHTRIE R.A. [2045] and Mary Eliza ROGERS [203], on 22 Oct 1903 in St Mathew West Kensington MDX. (Phyllis Isabell COUGHTRIE [2044] was born on 17 Nov 1876 in Hong Kong and died in Mar 1955 in Hemel Hempstead HRT.)

|

General Notes:

General Notes: