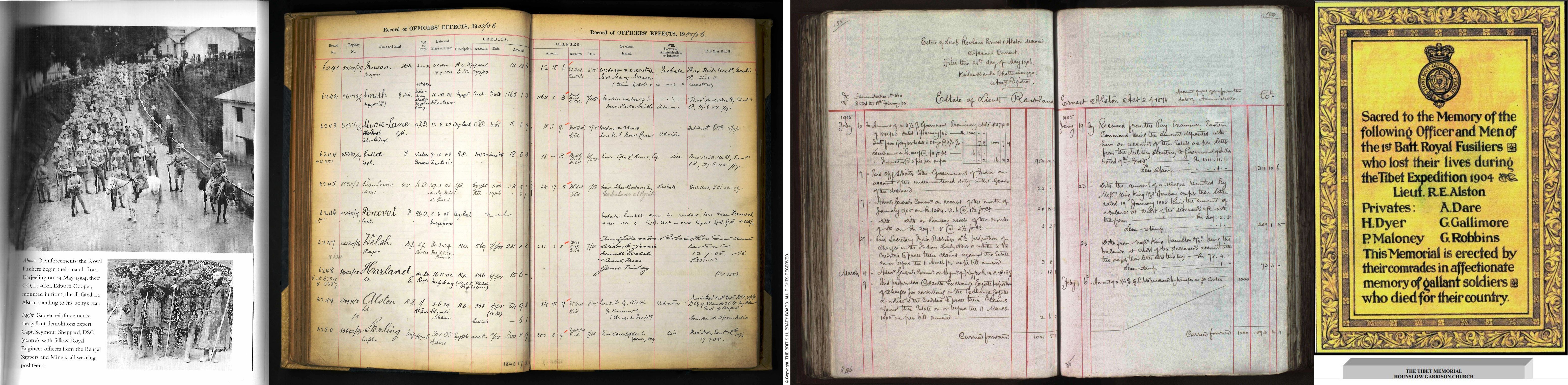

Capt Rowland Ernest ALSTON [4106]

- Born: 7 Jun 1874

- Baptised: 15 Jul 1874, St Michael Pimlico MDX

- Died: 28 May 1904, Tibet aged 29

- Buried: Chumbi Valley

Cause of his death was pneumonia. Cause of his death was pneumonia.

General Notes: General Notes:

Rowland went to Rugby, and was in Mr Donkin's House, he later served with the 3rd Bedfordshire Reg, then Royal Fusiliers, dying in Tibet.

Hunting.

A pretty Gallop from Norton Gorse by way of Houghton, Billesdon, Coplow, and Quemby to the ground of the Earl of Morton's covert in the Quorne country was afforded by Mr Fernie's hounds at Billesden yesterday. Though the line lay over quite a legitimate hunting country, there was any amount of grief in the course of the run, the fences, for once in a way, providing a greater source of disaster to the ladies than the men. Among the company were the Duchess of Hamilton,Lord Henry Paulet, the Earl of Lonsdale . . . . . Mr Rowland Alston, together with very many from the Quorn, Cottesmore, and Pytchley districts.

The Daily Telegraph Friday Feb 20th 1891

Colin Fenn writes 2008.

I've been looking into the British Invasion of Tibet 100 years ago, and came across this reference to an Alston in the Royal Fusiliers. Do you recognise the man? If so let me know & I'll forward you the rest of the article and an essay I'm writing about the campaign.

"Chumbi, 100 miles from Lebong was reached in ten marches, although at The Jelap La Pass the altitude was over 14000 feet. Almost continuous rain meant that the men rarely arrived in camp in dry clothes, which added to the risk of illness. Fitness was tested severely, although very few men reported sick. Lieutenant Alston was taken ill with severe mountain sickness, which was aggravated by acute pneumonia, and he died on May 28th. at Chumbi. "

Alston Rowland Ernest of 69 Ecclestone Square Middlesex died 3 June 1904 at Chumbi Sikkim India Administration London 21 Aug 1905 to Francis George Alston Lt Scots Guards effects £1848 1s 6d. National Probate Calendar.

Image Courtesy Roy Alston 2010

Research Notes: Research Notes:

The British Empire's Invasion of Tibet 1902-4

By Colin R Fenn

Exactly one century ago several thousand British and Indian troops forced their way into Lhasa, a city that had been closed to outsiders for a century. To get there they camped in winter snow at high altitude, and fought some of the highest land battles ever. For each soldier there were five porters and ten donkeys, mules, ponies, yaks, buffaloes, or camels shuttling supplies and fodder over frozen passes up to 17,000' high. The invasion of Tibet represented the last great Imperial adventure of the British Empire.

Background:

Throughout the 19th century a Cold War was fought between Britain and Russia over the Indian frontiers and Asian steppes. British players of the "Great Game" had watched with concern as Russia had extended its empire to the borders of Afghanistan throughout the 19th century, and had built railways that could rapidly move its armies almost to the borders of India. The game developed as Russia and Britain in turn tried to infiltrate explorers and spies across the buffer zones of Asia, including Tibet. At the start of the 20th Century Tibet was supposedly a protectorate of China and had been closed to the West for many generations. Neighbouring Sikkim was at that time a - nominally - independent monarchy, although both London and Lhasa believed it to be under their own protection. Plans for a British Imperial diplomatic mission to Lhasa in 1886 had been stonewalled by Tibet, and then abandoned after Chinese intervention. But while no-one else intervened, the British Empire was content to leave Tibet alone. Meanwhile a dozen British, French, and Russian explorers had ventured into Lhasa, but were all captured, killed, tortured or sent back. Indian pundits and Japanese adventurers had some success at infiltrating in disguise and mapping the major features of the country but only at great personal risk. The Royal Geographical Society in London awarded medals to many of these adventurers - even to the Russian explorers. But Britain was not prepared to ignore Tibet when she moved her troops through the border pass at Jelep La and into the north of Sikkim. The British Empire fought 3 short engagements and pushed the Tibetans back over the pass as far as the small Tibetan village of Chumbi, leaving 200 dead behind in return for only a few wounded. To resolve the problem an Anglo-Tibetan trade agreement was struck, and Sikkim formally became a British protectorate with a British Political Officer, John Claude White, assigned to the Sikkimese Court. But by 1901 the Viceroy of Imperial India, Lord Curzon of Hardinge, was concerned that Tibet was feting Russian influence, and would become a new threat to the stability of India's borders. Newspaper reports told of the travels of Khambo Agvan Dorzhiev, a Buddhist from Mongolian Buryiat and an envoy of the Dalai Lama who visited the Tsar. Over the next three years British intelligence1 brought back a stream of reports that this man had appeared in many places, peddling Russian influence and weapons and inciting the Tibetans against the Chinese and British. Curzon contacted the Chinese court, who became alarmed at the prospect of trouble on the borders of their sphere of influence. It sent out a replacement for its ineffectual Amban in Tibet, but because of obstruction and inefficiency it took 14 months before he could take up the post. Meanwhile Curzon had written to the Dalai Lama to resolve the dispute directly, but became slighted and suspicious when his letters were returned unopened. It is possible that they never reached the Dalai Lama, as he had been on a spiritual retreat for several years. In the summer of 1902 the Commander in Chief of India, Sir Power Palmer, was ordered to send 200 riflemen of the 8th Gurkhas to the north of Sikkim so they could map the Tibetan border and evict any encroaching Tibetans they found2. Although successful, they reported that the Tibetans were obstructive and would not engage in formal communications with them.

Preparing the Mission to Tibet:

Curzon had already met a young British Political Officer called Francis Younghusband who shared similar views about the conduct of the Great Game. So when Curzon was looking for someone to re-establish relations with and if necessary, punish the Tibetans he thought of Younghusband, who had had proved himself a competent explorer and a resilient character after the siege of Chitral, and was now looking for a new assignment after stagnating in a series of administrative appointments in Rajputana. Younghusband had already gained a reputation from his expeditions over the mountains of Hunza, when he had chance encounters with Russian Cossacks. He too was an exponent of the "Forward School" a British Russophobe, who believed in a forceful military strategy across the Hindu Kush and Pamir mountains. He left Curzon confident that he had a mandate to enter a short distance into Tibet to force them to negotiate, but not to go as far as Lhasa not immediately, anyway. There were a number of political considerations to bear in mind; Prime Minister Balfour in London was in the process of falling out with his old school friend Curzon, and preferred the Imperial maxim of "Masterly Inactivity". But Curzon was able to muster enough support from London to raise a force, although his Army officers were disappointed to find out that this would be toned down to the status of a "Mission", and not a formal "Expedition" that would automatically merit a military campaign medal. British Army lists frequently showed officers on leave or "shooting expeditions" in Russia and its Asian Empire, a euphemism for spying. Hopkirk has suggested that Ekai Kawaguchi, a Japanese infiltrator at the Dalai Lama's court, was also feeding information back to India to Iggulden. Song reports that Tibetans were forced out of the way with whips. Younghusband gathered together a set of important local dignitaries to support his Mission, including the Kumar of Sikkim and two other Political Officers: Frederick O'Connor, one of the few Tibetan speakers in the Army, and John Claude White, the long-serving and imperious PO of Sikkim. To make sure his Mission made an impact he asked for an escort of troops and an entourage.

The camp at Khamba Dzong: Initially Younghusband took the mission through the northern border of Sikkim where the frontier line had been disputed. He wished to attract the attention of senior Tibetans and the Chinese Amban at nearby Khamba Dzong on the Tibetan side of the border. (Tibetan administrative regions were normally controlled from Dzongs, garrisoned mountain or hill-forts, sometimes written Jong. Many of these dated back to more turbulent times, 500 years ago or more.) He was accompanied by a vanguard of 200 sepoys from the 23rd Pioneers under Captain Bethune, with another 300 following behind, supported by yaks and mules. However, Younghusband had received a telegram from the Viceroy at Simla ordering him not to advance into Tibetan territory until the delegates were waiting there. He chose to interpret this as applying to him only, and so, on 4th July 1903 he sent the rest of the force over the 17,000 ft pass at Kangra La, accompanied by White and O'Connor. Although there was a small scuffle when the troops went over the pass, within 3 days the force had set up its tents near the hill fort at Khamba Dzong. Younghusband followed on 18th July, where he was introduced to the local officers, two deputies of the lay Ministers ("Shapes") from Lhasa, and Prefect Ho Kuang Hsi, the sickly Chinese Resident's deputy from the major town of Shigatse. After listening to Younghusband recount the Empire's grievances the Lhasa delegates refused to receive any documents and then shunned him. Privately Ho admitted to his embarrassment at his lack of authority, this being the first time for decades that a Dalai Lama had survived into adulthood (the previous Dalai Lamas had died conveniently young, so that Tibet could be conveniently governed by a Chinese-appointed Regent.) Two Europeans in the pay of the Chinese government also arrived; Ernest Wilton of the Consular Service in Shanghai and Captain Parr, a translator and commissioner of the Yatong Customs Service. Parr was also convinced that Russia was sending materiel and troops into Tibet. All this time the Dzongpon (local district fort commander) profitably supplied the Mission with fodder and supplies, and was apparently pleased at this new source of income (although he complained that he could not charge the Chinese or Lhasa delegations). During the rest of July and August small teams were sent out from the Mission to hunt, map and identify grazing, fuel, and water supplies, and to gather intelligence; through this means they heard of a garrison of 250 troops at Phari Dzong to the south east, 500 at Dingri Dzong in the west, and the mustering of 2000-3000 troops near Shiagtse to the 3 Now a.k.a. "Xigaze" north, and calculated that Tibet could field a total of 6000 low grade troops and about 20,000 monks capable of bearing arms. Meanwhile the Mission's camp at Kamba Dzong was fortified with barbed wire, 4' high stone breastworks and a ditch. A wire was strung out to the Empire's highest telegraphic station at Kamba Dzong. Although the senior Tibetans guessed at the purpose of the telegraph wires, naive onlookers were told it was a string to help the Mission find their way home.The 23rd Pioneers under Colonel Macdonald of the Royal Engineers were assigned to the force in northern Sikkim to work on improvements to the mule tracks and to give visible support the Mission4. By September, conditions had deteriorated in several ways. Before the first snowfalls there had been a welcome issue of thick blankets, sheepskin poshteen coats, padded trousers, Gilgit boots, vests, and cardigans, plus balaclavas for the officers and Gurkhas. Even though a Lama had now joined the list of Tibetan delegates, no Tibetan was prepared to make a decision, and both sides remained un-reconciled. Younghusband gave orders to eject those few Tibetans still in the disputed border area and to seize Tibetan cattle to the value of 2000 Rupees as an indemnity when two Sikkimese "traders" under British protection were abducted. The Chinese were also becoming anxious their new Amban, Yu Tai, was still held up en-route to Lhasa, and the local Tibetans were refusing him supplies. He wrote home that the three Shapes from the big monasteries were guiding Tibet towards war. Younghusband became increasingly fractious, and sent PO White back to Sikkim, where he spent the rest of the campaign. Younghusband and the Viceroy were becoming increasingly exasperated with the Tibetans, and were starting to spoil for a fight. The Nepalese Prime Minister Maharaja Chandra Shamsher Jang sent letters to Lhasa recommending co-operation, and showed support to the Mission by sending more yaks. However the beasts never arrived, as the first herd was scattered by Tibetans, while the drivers of the second herd gave up after several men froze to death on the mountain passes. In November 1903 Viceroy Curzon wrote of this "attack" on the yaks as "an overt act of hostility". Meanwhile support for action in London had resulted in King Edward VIII privately recommending a more aggressive approach6. In exasperation, on December 12th 1903 Lt Col Brander withdrew the whole force from Khamba Dzong. On the same day Younghusband appeared at the head of a much larger aggressive force that advanced over the pass at Jelep La and into the southern tip of Tibet. 4 TSO 5 Many modern sources believe these "traders" were pundits used to reconnoitre the area ahead. 6 OIOC, Mss Eur C313/38

The advance into the Chumbi Valley:

The 14,390 ft southern pass at Jelep La was icy but un-seasonally clear of snow when the enlarged Mission's advance column traversed it carrying three day's supplies. It was formed of 6 coys of the 23rd Pioneers and 4 coys. 8th Gurkhas, four artillery pieces, a pair of machine guns from the Norfolk Regiment, and half a coy. Sappers and Miners, and was followed the next day by a long supply line of coolies, yaks, and ponies. Although the distance was only 5 miles horizontally, the first march required an ascent of 2000 feet and a descent of almost 5000 feet, taking up most of the day and part of the night (equivalent to descending the South Rim of the Grand Canyon!) The nearby Sikkimese town of Gnatong was used as an advanced base for the lines of communications by Macdonald, who closely followed the advance with more ammunition and supplies. During the summer the new C-in-C India, Lord Kitchener, had agreed with the Viceroy to supply Younghusband with an initial military contingent of about 3000 fighting men under the control of McDonald7: 23rd Sikh Pioneers (8 coys.) including their 2 Maxim machine guns 32nd Sikh Pioneers (8 coys.) including their 2 Maxim machine guns 8th Gurkhas (6 coys.) including two 1860-vintage 7 pdr. RM portable guns nicknamed "Bubble" and "Squeak" N0 7 Mountain Battery of Royal Artillery: 1 section with two 10 pdr. screw guns N0 3 Coy. Bengal Sappers and Miners N0 12 Coy. Madras Sappers and Miners Norfolk Regiment: 1 detachment of 2 Maxim machine guns8 Initially a total of 50 men were drafted from 23rd, 32nd Sikhs and 8th Gurkhas and trained as Mounted Infantry on 12-13 hand supply ponies. More were trained and eventually formed into the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Mounted Infantry coys, of 108 men each. Mounted infantry Improvised from Sikh and Gurkha units using supply ponies (Landon) The support and lines of communication included: 7 Iggulden. MacDonald received a Brevet Rank of Brigadier General for this Mission. 8 Iggulden suggestes the Norfolks were selected in November 1903 as a "token" British Army contingent. 1 section British and 4 sections Native Field Hospitals. Later in the campaign this was expanded to 12 Field hospitals and one base hospital. There were also sections of military police, post office, and telegraph; the signals sections being drafted from several other regiments, including the Rifle Brigade, Royal Sussex and Devon Regiments. An enormous Coolie Corps was raised in Sikkim for the expedition (put at 8-10,000 men and several hundred women9). In addition to the flocks of sheep kept for fresh meat, at various places they used 10,900 donkeys, mules and ponies, 9,225 Nepalese yaks and Indian buffaloes, and 6 camels for transport10. (Soon many of these animals suffered from disease: only 40 or so yaks survived anthrax, rinderpest, and pneumonia, while foot and mouth eventually killed most of the buffaloes). At high-altitude the Mission was reliant on thousands of human baggage carriers, who sometimes had to be cajoled and tricked to overcome desertion and superstitious fears. Pack Yak and its handler The yak is harnessed to an ekka, a dismantlable light Indian cart (Candler) The force was unopposed and marched north through the southern-most valley of Tibet, passing unopposed through Yatung, Rinchengong, Chumbi and up the river Ammo11 until they entered the un-garrisoned fort at Phari Dzong, 40 miles north of the border pass. It was thought this occupation was unopposed because the main Tibetan army was not expecting any action in the southern valleys 12. The troops were received cordially, the local villagers happily sold them supplies and grazing until three monks were seen to arrive from Lhasa and gave orders that forbade anyone trading with the Mission. Nonetheless, they passed a tolerable Christmas day here, with the officer's mess tables groaning under a full complement of turkeys, hams, and puddings, the event marred only by the champagne, flat because of the cold. As these monks still refused to meet the Mission, on 8-9th January 1904 an increasingly frustrated Younghusband took an advanced column of 300 men (including 4 coys 23rd Pioneers, 20 Madras Sappers, a 7 pdr., and the Norfolk's machine gun section, under Lt Col Hogge.) to a further camp spot at 15,000' at Tuna13, a hard march of 15 miles against 9 Iggulden (8,000), Hopkirk (10,000) 10 French 11 modern "Torsa Chuu" 12 Ottley 13 aka "Thuna" a headwind of flying ice splinters, and over the 15,700' pass at Tang La. It was here, in a wind-swept valley between 24,000' high snow-capped peaks, that he chose to wait for the Tibetan delegation. The Mission waited for three months at Tuna. During this time mounted reconnaissance went up to the mountain passes and identified a camp of 2,000 Tibetans 12 miles to the north-west, including 600 at the village of Guru; most of the Tibetan force had matchlock muskets or spears, which were less susceptible to the harsh conditions. Their movements were communicated by heliograph back to Tuna. Fortunately neither side had martial intentions, as the Mission had discovered their rifles were prone to seizing due to thickening of the gun oil. Men stripped and slept with their gun mechanisms to try to stop them freezing, while the machine gun crews poured rum into the barrel casings as an anti-freeze (mixed with kerosene to make it undrinkable) 14. The Post Office telegraphic section suffered dozens of cases of frostbite as they followed behind, stringing cable between poles. The fortified camp of the Mission who preferred to sleep in their tents near a river, rather than the few local vermin-infested huts heated by open yak dung fires - remained here until 31st March 1904, through snowfalls, winds, electrical storms, and days when the temperature stayed below freezing. The men grew beards which were soon coated in ice. Although the snows were late that year, night time temperatures could drop dramatically, reaching -41.5 O F on one occasion. Most of the camp developed coughs, and over time several men died of pneumonia. However, Colonel Younghusband and "Retiring Mac" (as the Brigadier General was now nicknamed) had fallen out over the conduct of the mission so that the split force suited both senior officers; MacDonald chose to spend his time in the relative comfort of the southern supply lines, while Younghusband explored the stunning mountains and his own spirituality in the icy vanguard. Nor was any effective communication made with the Tibetans, who were now too scared to deal with Younghusband. (The Dalai Lama had already tortured and imprisoned one of his Shapes over this affair). The Viceroy agreed that Mission should force action by advancing 86 miles north towards Lhasa, past the Tibetan encampment at Guru en route to Tibet's third largest town of Gyantse15.

Bloodbath at Guru:

On 31st March Macdonald came to the front and led an advance out of Tuna towards Guru though 6 inches of fresh snow. Macdonald had gathered about 700 troops16: one and a half coys. Mounted Infantry (details from the Gurkhas and Pioneers), 3 coys. 23rd Pioneers, 14 Hadow 15 Modern "Gyangse" 16 TSO 4 coys. 32nd Pioneers 2 coys. 8th Gurkhas, Norfolk machine gun section, all 4 artillery pieces, and one field hospital India had now given Macdonald command of the force, which was now a military operation, and, although his force was under instructions not to fire first, he decided to make a surprise overnight attack on the Tibetan camp17. Younghusband argued that things should be resolved openly and peacefully. In the end, the attack was cancelled and the force marched quietly up to the Tibetan positions in daylight, and attempted a fruitless parley. About 2,000 Tibetan18 soldiers under the Depon (General) Lhading of Lhasa, armed with swords, spears and breach loaders, waited at Chumbi Shengo19 across a crest of a mountain spur, either behind a 5' high wall that lead down to a hut in a muddy plain, or behind low sangars that they had built on the slopes. They too had instructions not to make the first move, but were also ordered not to let the Mission pass. They were mainly "dob-dob" warrior monks from Ganden, Drepung and Sera monasteries, led by Trungche (Secretary General of the Dalai Lama) Lozang Trinley, and a local militia from Phari commanded by Dzongpon (Fort commander) Kyibuk; The parley at Guru seated left-right : General Macdonald, Colonel Younghusband, Depon Lhading, Shigatse Lhading (Landon) While Macdonald and Younghusband parleyed with the Depons, he despatched several companies to climb the slopes and outflank the Tibetan positions. Their meeting broke up unsatisfactorily. He then instructed a number of sepoys to go in and disarm the Tibetans. Accounts are contradictory over the next step; contemporary British military and newspaper accounts say that a Tibetan, possibly the Depon Lhading, initiated hostilities by discharging a pistol towards a sepoy. Other Tibetan accounts say they were ordered to 17 French 18 TSO, French 19 Chumi Shengo, "Hot Springs" snuff out their matchlock fuses. They all concur that there was a gunshot and a scuffle which triggered a massive and intense fire from the gathered Lee Metfields, Lee Enfields, Maxims and artillery firing shrapnel into the mass of Tibetans, a fusillade that lasted "for the length of time it would take six successive cups of hot tea to cool"20. In spite of their protective magic amulets and spells at least 200 Tibetans lay dead. The toll would have been higher, had not some men stopped firing out of pity, and had the weapons been more reliable; the Norfolk machine gun section reported "the high attitude and extreme cold affected the metal, springs, and cordite, in ways which we never understood"21. Mounted infantry was sent in close pursuit of the routed Tibetans, while other parts of the force advanced into the 3 hamlets of Guru. They all reformed and returned to Tuna by 7pm, while the Tibetan forces retired towards Gyantse. Chumbi Shengo. Volleys have just been fired into the Tibetan body of soldiers, who have withdrawn. Sepoys in positions behind a low wall while others go up the valley walls in pursuit. (Landon) Macdonald's report recorded 500 Tibetans left dead or wounded, 200 prisoners, and 60 captured yaks, at a cost of one injured officer, 10 wounded sepoys, and one wounded newspaper correspondent, Edmund Candler from the London Daily Mail22. The Tibetan dead included Depon Lhading, his deputy and servants, Depon Namseling from Shigatse, Kyibuk the Dzongpon of Phari, and two Lamas. A few Russian-made breach loading guns were found on the battlefield, along with some Russian ammunition. 20 French. Accounts disagree, French states there were 200 wounded and 628 killed. 21 Hadow. 22 However, the climate was more deadly. On April 24Th 1904 Macdonald reported the deaths to date of 35 combatants and 45 coolies, almost all due to the cold. In addition there were another 130 cases of frostbite.

Advance to Gyantse:

The Mission resumed its march to Gyantse on 4th April, through snow storms along a level plain at 14,900', leaving supply posts behind at Guru and then every 12 miles. On the 7th April ten 2nd Mounted Infantry scouts came under inaccurate musket fire from Tibetans occupying the village of Kalatso. They returned fire, before retiring. Overnight the village was abandoned and occupied. Six dead were found behind 2ft thick turf. Several times the scouts came across abandoned defensive walls spanning valleys. 23 18 miles before Gyantse, in the mountain gorge of Zamdung ("Red Idol"), a stand was made by the Tibetans who took advantage of the cover provided by boulders and cliffs: Gurkhas were sent on a 4-hour mountaineering climb in a snowstorm to outflank their position while gunshots were exchanged between positions. The Tibetans broke and fled, leaving 200 dead, after the weather cleared and the Gurkhas achieved their vantage point where they were able to enfilade the defenders with rifle fire. The column reached Gyantse at 13,000' on 12 April 1904. No resistance was offered and they raided all the grain they found from the 600' high Dzong and nearby monastery, They also emptied out all the armouries, but there were several accidental fatalities through explosions when they attempted to empty the powder stores. Deciding that the Djong was too large to defend, Macdonald set up camp 1,100 yards away in a rented mansion at Chung Lu. There were two buildings with a clear view across the plain, adjacent to the Nyang River, with grazing, willow trees, and a walled enclosure which the Pioneers were tasked with reinforcing with trenches, revetments, spiky bushes and sections of barbed wire. While a daily market and a popular medical dispensary were held outside the camp Younghusband must have sat and wondered who was left for the Dalai Lama to send to negotiate a treaty - the Chinese Amban had sent a message saying that most of the senior Tibetan Ministers were now imprisoned over this affair. After a week Macdonald took this opportunity to retrace his route back to the border with the main force, leaving Younghusband and Lt Col Brander to their tents in the snow at Gyantse with 6 coys infantry, the two 7 pdrs., the Norfolk Maxims, 50 mounted infantry, 200 mules and drivers, and a few sick men. By the end of April a large force of Tibetans was observed gathering at the 16,500' high pass of Karo La, 42 miles east of Gyantse towards Lhasa, and potentially threatening the British supply route. Brander decided to strike rapidly, and in early May took a Flying Column of three companies of 32nd Pioneers, one coy Gurkhas, the two 7 pdrs., and the Norfolk's Maxims to the pass, leaving Major Murray of the 8th Gurkhas behind, in command of 80. 23 Candler: "Wall-building is an instinct with them. When a Tibetan sees two stones by the roadside, he cannot resist placing one the top of the other". Glacier over the Karo La However, at the Karo pass the Flying Column saw a near impregnable position manned by 2-3,000 levied Kham Tibetans. Flanking an 800-yard long defensive stone wall were sheer cliffs and well-placed sangars behind a glacier that allowed the Tibetans to invisibly enfilade the attackers. The Tibetans released a controlled avalanche, but they were too premature and the scouting force targeted was able to duck behind cover. The British antique 7 pdrs. were fired like howitzers, but were useless; they were inaccurate even at 600 yards and many shells landed badly and failed to explode. After an exchange of rifle fire from 1,000 yards and a frontal infantry charge, which did little except waste ammunition and get several exposed men killed, Brander despatched sections from his Gurkhas to scale the cliffs that overlooked the Tibetan flank, which were already high on the slopes. After three hours, those men had reached 18,500'-19,000' and were getting into position when the clouds cleared and gave the Tibetans clear targets from behind their sangars. An impasse had been reached and the attack was likely to be called off. However, a dozen Sikhs were able to take up position on the other flank and set down a well-aimed fire. The nearest Tibetans suddenly bolted and ran from their position, soon followed by the rest of their force. The Mounted Infantry and Sikhs pursued them for several miles and caused many casualties, for a total loss of one officer and 5 men killed, and 13 wounded. Brander's column had to return to Gyantse quickly, for they had received two urgent dispatches en-route to Karo La; one was from Younghusband, informing them that Gyantse had come under attack; the second was from Macdonald, rebuking Brander for going to Karo La24. 24 Candler wrote "A weak commander might have faltered and weighed the odds . . . . . But the sortie is one of the many instances that our interests are best cared for by men who are beyond the telegraph-poles, and can act on their own initiative without reference to Government offices in Simla" While Brander had been away, an army estimated at 1,600-2,000 men had come south from Shigatse and Kham25, and, notified that the fort was undermanned, assaulted the Chung Lu camp before dawn on 5th May. They had been able to reach the loopholes in the defensive walls undetected, and may have achieved complete surprise had they not woken everyone by yelling loudly before attacking. The 80 British defenders, many still wearing their pyjamas, were able to grab their rifles and beat them off, leaving 200 Tibetan dead receiving only slight casualties in return. However, the British force was too small to prevent those Tibetans re-entering the Dzong, and killing a number of coolies and camp followers who were sleeping there. The Dzong provided a commanding position overlooking the fortified mansion, but as neither side was sufficiently strong to besiege the other a sniping and raiding war developed over the next eight weeks. Although the new force was more warlike and better-led, the Tibetans' matchlocks were too inaccurate and only had a few modern rifles and ancient jingals that could fire at this range. Their shots were traded with more accurate rounds from a Lee Metfield or Maxim, which ensured each side kept safely behind their walls during daylight. Meantime the Tibetan commander built up the walls of the Dzong and created a defensive perimeter of about 7 miles length. Both side's artillery was practically useless; the British 7 pdrs. had too little high explosive ammunition and their star shell ammunition was often defective. The Tibetans were reinforced by by a single heavy Tibetan piece but it presented too good a sniping target to be used effectively. The Maxims were used regularly for sniping, which dissuaded all Tibetan cavalry or supply ponies from venturing out during the day and made sure no Tibetan looked out of a loophole for long. It took 19 seconds for a Maxim round to travel 3,600 yards across the plain, and the fall of shot was carefully tracked by field glasses in the clear air. However the Tibetans discovered that a safe shelter could be obtained by building up a wall overnight, and used this as base for sharp shooters and night-time raiding, especially around the outbuildings of the nearby hamlet of Pala. Raids from the British camp secured these buildings on 26 May and the site was used for sniping against the Djong. Around this time some reinforcements slipped in overnightl; one and a half coys of Bengal Sappers & Miners, a coy of 32nd Pioneers, and two of the more accurate10 pdr guns of the 7th (British) Mountain Battery. The raids around Gyantse kept the Tibetans' attention off the supply lines; only once on 7th June did they assault a supply post 20 miles east of Gyantse; the company of 23rd Pioneers were co-incidentally reinforced that night by a passing escort of 50 Gurkhas and the raid was beaten off, leaving 150 dead behind. All this sniping and raiding came at a cost; the British sustained 68 casualties over the eight weeks at Chung Lu, the Tibetans many, many more so. Younghusband became more and more frustrated; he was insistent that the Tibetans would not negotiate unless they advanced into Lhasa and stayed there until agreement was reached, but Macdonald had delayed them again, and put everyone under his direct 25 Kham was then considered part of Tibet control since Brander had exceeded his orders by attacking the Karo La, and made the force wait there. Younghusband's frequent telegrams re-iterated this point and he threatened to resign if the Government of India continued to disagree with him. (Viceroy Curzon was now in Britain and had other priorities26; Kitchener and Ampthill, the deputy Viceroy, and had become nervous over the Mission and felt the mood of the London Parliament as expressed by the Secretary of State was now uncertain.) There were rumours that resistance was being organised by a Russian monk, Zerempil27, and that Tibetan monks had gone into Mongolia to raise funds and mobilise horsemen28. Eventually all agreed to advance; but only if the Tibetans refused to come to Gyantse to negotiate within a month. So an ultimatum requesting their presence by 25 June 1904 was drawn up on parchment, sealed with wax and ribbons, and sent over to the Dzong, only to be returned unopened29. Macdonald summoned Younghusband to join him, and he slipped out of camp with a small mounted escort before dawn on 6 June 1904 and rode hard to the Sikkim border. After another skirmish at a supply base en route, he was able to slip away and reach the south, where, after several heated telegraphic exchanges between Younghusband, Macdonald, Ampthill and Kitchener, a plan was hatched amongst the rhododendrons and primulas for the invasion of Lhasa.

Assault on Gyantse:

British intelligence now indicated that the whole Tibetan army was mobilized, including their most highly regarded soldiers from the eastern regions. Intelligence estimated they were distributed as follows 30; 6-8,000 men in Gyantse Dzong, 800 monks in a nunnery south of Gyantse, threatening the British supply route 800 men 15 miles east of the above force 1,200 men guarding the Lhasa route 18 miles east of Gyantse 3,200 men north of Gyantse holding the route to Shigatse or in Penam Dzong Another 2,000 men were estimated to be in the area near the Karo pass. As a result of the earlier communications with India and London, a full military expedition had assembled at the Tibet-Sikkim border; the previous Imperial Mission was now to be augmented by: 8 mountain guns 19th Punjabis 40th Pathan Infantry (nicknamed "the Forty Thieves") Royal Fusiliers (4 coys) with the machine gun team from 1st Bn Royal Irish Rifles 26 Curzon was desperate for a male heir, and his expectant wife had miscarried and very nearly died after they returned to England. Meanwhile his policies were attacked; one of his Foreign and Colonial Office detractors saw this visit as an opportunity when " we can shake him by the neck, which we cannot do by cable" ref: Onslow/St John Broderick papers OIEC G173/24/83 18 May 1904. 27 Hopkirk 28 The Times, June 2, 1904 29 French 30 Iggulden. 2nd Mounted Infantry (2 additional coys) more field hospitals, and an even larger line of communication and supply. The force set out from Chumbi on 12th and 13th June 1904 in two columns, though their speed and effectiveness was hampered by altitude sickness and pneumonia as the reinforcements had not had time acclimatise to the conditions. En-route there was an engagement at Naini31, about 7 miles south of Gyantse, where 800 armed monks made a stand at a nunnery on June 25th. The Norfolk's machine detachment had slipped out of Chung Lu during the night to achieve a vantage point 3,000' above the nunnery. Their fire was used to support a pincer action by a detachment from the main force when many monks were killed or fled, for a loss of 3 men and 7 wounded32. The Tibetans retreated into the nunnery's small dark rooms and cellars; by pushing their helmets and turbans in front, the British troops would trick the Tibetans into taking premature shots with their matchlocks and were thus able to engage them at bayonet point. It appears this resulted in significant damage to the temple, its statues, and important Indo-Nepalese paintings33. A follow-on assault on a nearby village at Thagu was cancelled at the last minute when news reached them of a possible Tibetan attack on the Mission. Two days later on 28th June the force linked up with Brander's vanguard at the camp at Chung Lu, while the 40th Pathans, 8th Gurkhas, and artillery, forcibly evicted the Tibetan forces from a dominating ridge in the north. Meanwhile the Royal Fusiliers cleared and occupied some outlying villages and the Monastery of Tse Chan east of Gyantse. These actions isolated the Tibetan force at the Dzong and cut off its water supplies34. A bridge was assembled across the Nyang River to facilitate manoeuvres across the northern plain. Tibetan soldiers Disarmed of their swords, spears and matchlocks (Candler) 31 Hadow, Ottley [Official British military records call this action at Nenying "Naini"] 32 Iggulden notes 16 casualties including one Major 33 French, quoting the Phuntsog Tsering. Newman mentions that four towers and a hall were blown up after a convoy had been fired on from Naini. 34 Royal Fusiliers Regimental History On 29th June an armistice was called, and on 2nd July a group of Tibetan monks arrived to parley, but to no positive effect. On 5th July a sickly Macdonald issued his orders for the assault on the Dzong. For the first day a strong diversionary attack was made on a hamlet to the north-west, by 2 coys Royal Fusiliers and a detachment of 8th Gurkhas supported by their mountain battery. Although these positions were badly overlooked by the Tibetans in the Dzong, the village was taken and fires were left burning overnight to distract the defenders. After dark the troops passed back over the new bridge and rejoined the main body to the south for the next day's assault. Macdonald's orders for the day were split into 15 points35: 1. The Jong will be assaulted at 4am on the 6th of by 3 columns as under: Right Column Centre Column Left Column Under Capt Johnson Under Capt Maclachlan Under Major Murray Dett Sappers & Miners Dett Sappers & Miners Dett Sappers & Miners 1 Coy Royal Fusiliers 1 Coy 40th Pathans 1 Coy 8th Gurkhas 1 Coy 23rd Pioneers 1 Coy 23rd Pioneers 1 Coy 32nd Pioneers 1 7pdr. gun Reserves 1 Coy Royal Fusiliers 2 Cos 40th Pathans 1 Coy 8th Gurkhas 1 Coy 23rd Pioneers 1 Coy 32nd Pioneers Camp Guard 1 Coy 40th Pathans 1 Cos Royal Fusiliers 1 Coy 8th Gurkhas 1 Coy 23rd Pioneers 1 Coy 32rd Pioneers The remaining troops will form reserve to Camp Guard 2. The attacking column the first day will be relieved at dusk by the reserve and will return to camp His remaining points went on to state that Lt Col Campbell should command the assaulting columns on the first day, that each column should be allocated explosives and crowbars, and identified responsibilities for fulfilling these commands. Charges were exploded at 3am in the southern part of the town, and a major assault commenced across the three columns. By midday the force had established its position at the foot of the Dzong, and at 2pm they requested all fire from the 10 pdrs. to be concentrated on the Dzong walls using conventional explosive. Supported by overhead fire from the Maxims, the 8th Gurkhas scaled the 600' high steep slopes to the Dzong through a 12' wide breach. Havildar Pun and Lt Grant VC were both decorated for their efforts in storming the breach. The Gurkhas were closely followed by 2 coys of the Royal Fusiliers, helped by a lucky artillery hit on a Tibetan powder magazine. Although there was fierce initial resistance with the defenders throwing boulders over tiers of ramparts, 35 Ottley the Tibetans soon fell back to the north, and the Dzong was captured by 5pm, at a cost of about 50 injured. Gyantse Dzong Showing the steep glacis and the breach in the upper fortress that was stormed by Pun and Grant. (Landon) The attackers held their position overnight, ready for an assault on the neighbouring monastery to the east of the Dzong the next day. An assault party was formed, but only encountered four British troops who had already noticed that the buildings were unoccupied, and thought they might help themselves to some loot36. The Tibetan resistance in the face of 12 guns, 10 Maxims, and 2,000 Lee Metfords, was well respected, although in the end they only inflicted a total of 37 casualties on the invading force. However there were several deaths and injuries in the days that immediately followed as the Dzong was made safe. On two occasions black powder was accidentally ignited as it was being removed.

Advance to Lhasa:

36 Hadow, Ottley. Although one of the Medical Officers was an antiquarian with links to the British Museum, looting by individuals was not allowed. Soldiers were forced to hand anything back if caught by staff officers. On 14th July 1904, through freezing rain, a column set out from Gyantse to march 140 miles to Lhasa via the eastern route over the Karo La, led by Macdonald and Young-Husband. It comprised37: 200 Mounted Infantry in 2 coys, 8 guns of 7th and 30th Mountain Btty, 80 men of 1st Madras Sappers and Miners 900 Infantry; 8 coys 8th Gurkhas, 5 coy 32nd Pioneers, 4 coys 40th Pathans, 4 coys Royal Fusiliers, including 4 Maxims, plus the 2 Maxims of the Norfolk Regiment They carried 23 days rations on 3,900 mules with 2,000 drivers. Left behind in Gyantse were 8 coys of infantry including the 23rd Pioneers, 50 Mounted Infantry, and 4 guns. Another 70 Mounted Infantry and 400 men were left at strategic points en route to Lhasa38. On the 17th July this force camped at 16,400', by the glacier at Karo La, in the knowledge that again a very large force of Tibetans held a strong position beyond the pass two miles away. However, most of that force dispersed rapidly, leaving 1,000 levies behind to hold a constriction in the pass below the snow and between two sheer cliffs and some caves. The eastern cliff was judged climbable, and on 19th July some Gurkhas and Royal Fusilier signallers were sent up on a five-hour climb to fire on the levies. The Tibetans broke and retreated over snow fields at 20,000', where it was not possible to follow. The next day the British force descended through the Red Idol Gorge towards the monastery at Nagartse to find their route was briefly barred by 50 mounted Tibetans in chain mail. Before they were able to reach close quarters most were shot down and killed by rifle fire, and the others fled39. Inspecting the monastery they now felt sure they were on the trail of the Russians, as they had discovered more Russian Berdan riles, plus Winchester repeater rifles, Sniders and Mausers40. They proceeded unopposed past the great lake of Yamdok Cho41, and then down 4,000' into the fertile Tsangpo42 valley. The Mounted Infantry nearly caught up with the tail of the Tibetan Army that was attempting to cross the river at Chaksam43. There they were able to purchase additional supplies and requisitioned two large ferry boats and a number of yak-skin boats which were used to ferry everyone across the river for the next seven 37 Iggulden cites 1180 rifles. The Royal Fusiliers' history cites 2000 rifles. Landon cites 2500 rifles and 150 officers, based on Iggulden's own detailed notes, including: 6 10pdrs. of the 7th MB, 2 7pdrs. of the 30th MB, 2 coys. MI, 20 infantry coys, 3 field hospitals . He itemises the medal list of officers who made it to Lhasa. Candler gives the most detailed description cited above. 38 Ottley. Candler indicates Pathans and Gurkhas were left at Ralung, Nagartse, Pehte, Chaksam, & Toilung 39 Royal Fusiliers 40 It has been suggested by McKay that the Berdan rifles were Russian modifications of a shipment of obsolete 30-year old American-made rifles, that carried both English and Cyrillic stamps 41 Modern "Yum Co" or "Yam Cho" 42 The Survey of India had recently discovered that the Tsangpo ("Zangbo") was the upper reach of the Brahmaputra 43 Iggulden (aka Chang sam, probably near modern "Kung Ka") days. Macdonald had also brought a dozen folding Berthon boats over the mountains, but these proved inadequate and were discarded after a Major drowned when his boat was caught up in a whirlpool. Tibetan ferry boat Loading sepoys and ponies onto a ferry boat on the Tsangpo River at Chaksam, while a yakskin boat looks on in the distance. (Landon) The force marched north straight through the valley to Lhasa and met no more resistance, other than peaceful, if truculent, deputations of monks and minister Tsarong Wangchuk Gyalpo from the capital. Ignoring the residential city, the force entered the gilded Potala Palace at Lhasa on 3rd August to find the Dalai Lama had already fled, along with any elusive Russians. Affairs of state were once again in the hands of a Chinese-controlled Regent, Lamoshar Lobshang Gyalten, and the Tibetan lay Ministers, who had now been released from jail. The force built a tented camp outside the city, encircled by a zariba44, a sharp thicket fence. Aware that negotiations would have to be concluded before the Mission was snowed in, the monks were prompted into participation by sending out a show of force towards their monasteries. When not intimidating the monks, troops amused themselves with sightseeing, football, rifle competitions, and pony races. Surprisingly, in the markets they found English biscuits and buttons, Scottish cotton, and even a bicycle. Officers were disappointed to be told that they were not to offend the Lhasa Buddhists by hunting, particularly as the local had become so trusting that they were easy targets. 44 Macdonald had served in Africa where these improvised defences were originally used. Mounted Infantry Officer's mess at Lhasa. Front row: Lt Bailey & Lt Rybar. Back row: Capt. Ottley, Maj. Dunlop, Mr Candler of the "Daily Mail". Note flowerpots and orderly in background. (Ottley/Bailey) Eventually, on 7th September, an agreement was struck and Younghusband donned his full commissioner's uniform, and signed a new Treaty at the Potala Palace that recognised the original 1880 trade agreement and granted exclusive access to the Lhasa court to the British. The Amban proposed a clause that Tibet was under sole protection of China but this was rejected45. An enormous indemnity was levied for payment over 75 annual instalments, with the right to station a British resident with a force of troops in the Chumbi Valley until it was discharged. This was much more than had been originally expected, and when London was told of it they telegraphed Younghusband to scale it down. Although he received their message in Lhasa he thought it was too late to take action, as his force was just about to depart. The Mission left Lhasa on 23rd September 1904, by which time the first frosts had already started. They marched for 400 miles following an approximately similar route back to the Sikkimese border. The weather had broken and they had to traverse snowfields and severe blizzards; they had left some of their winter clothing at Gyantse, and, although the Mission had purchased thick woollen ponchos in Lhasa, their sun spectacles, boots and their clothing were broken or worn out, and one man died on the pass at Tang La and 200 were stricken with snow blindness. The units met up for demobbing at Chumbi on 19th October, prior to marching through the leech-infested tropical forests of Sikkim en-route to their depots in India. Total British military losses to hostile action were 37 killed and 167 wounded. Deaths due to accidents and exposure were considerably higher, though not recorded to the same detail. Tibetan losses due to military action were estimated at 2700.

Aftermath:

Politically, the results were problematic for all sides. 45 Song Liming. Amban Yu's diary Against Chinese advice, the Dalai Lama and the monk Dorzhiev had escaped to Mongolia several days before Lhasa was occupied. The remaining Tibetan representatives were conciliatory and rapidly ceded terms. Although there was concern in the British Mission that the agreement could not be made binding, the Chinese declared the Dalai Lama had been deposed and replaced him by a Chinese-appointed Regent who agreed terms. Significantly this three-way international agreement gave de facto recognition of Tibet's national autonomy, and is still cited by organisations involved in Tibetan and Chinese affairs. It had soon become obvious that the original purpose of the Mission had been mistaken: Russian guns and ammunition were the only hints of influence found. When they to Lhasa they found no evidence that the Tsar had made any significant incursions into Tibet. Their own experience pointed out the futility of an invasion from the north. The Russian translator on the Mission, Capt Boome, was left behind before they went up to Lhasa. Yet hidden behind the scenes there had been Russian intrigue. It now appears that there was a dialogue developing between the two courts: in reaction to the British Mission Naran Ulanov arrived in Lhasa to offer St Petersburg's support in February 1904, meantime Kuropatkin made plans for a military expedition in the summer but events in the Japanese-Russian war overtook them46. The battle at Guru has gone down in Tibetan lore as a massacre; and as a result Lhasa was forced to confront the Modern World after centuries of isolation. In hindsight, it is obvious that the Tibetans had a complete misunderstanding of European methods and weapons; they had been so isolated that they thought it was possible to dismiss relationships between other nations whatever they were - as "not according to their custom". Although Tibetan warriors were fierce and raised to be tough, they had not learnt from their earlier experience of fighting a European-style army on the Sikkim borders. The south western armies were only used to border skirmishes against lightlyarmed and superstitious bandits, or Nepalese and Sikkimese troops, who did not wish to stay long in their inclement country. They chose to fight in set-piece battles in the open valleys, rather than skirmishes by the forests or in the mountains. They seemed ignorant of the British force's vulnerable lines of communication. Their soldiers were unused to running quickly into battle as they believed that their spells and charms would be sufficient defence. Their technology was largely limited to spears or breech loading muskets that were only accurate to about 150 yards, and hopelessly inaccurate Jingals that could throw a 1 lb shot for two thousand yards or more. Modern repeating rifles and heavy artillery were scarce. And after a battle, the injured did not understand how or why the Indian Medical Service was attending to their wounds. The Tibetan theocratic ruling classes were also afraid that free trade would affect their privileges and standing; the Chinese had fed this fear by intimating that Buddhism would 46 Until recently there was no documentary proof available to show Russian intent. McKay found reference to these expeditions in St Petersburg archives. be overthrown by the British47, and meanwhile made sure that the major monasteries received free Chinese tea and other staples to keep them in favour. In this way the 13th Dalai Lama was given a hard introduction to global politics. The British, in turn, did not understand the mindset or the inert nature of the resistance shown; they gladly acknowledged the smiles and applause of villagers, not knowing that clapping was a Tibetan way to drive out devils. Nonetheless, Younghusband's expedition was widely reported in the newspapers in London as a great success, and he was feted as a popular hero by the press and the King back home as the man who had at last entered the Forbidden City. Photographs, stories, and books hit the market as soon as they could be printed, and stimulated an interest in all things Tibetan. However it rapidly became obvious that the London government did not want the Tibetan treaty, and did not appreciate the public attention. The Conservative Prime Minister Balfour and, from 1905 his Liberal successors, were then building the "Entente Cordiale" with France and her ally Russia; they were already embarrassed that Britain's Japanese ally had so thoroughly humiliated the Russians in the Russo-Japanese war of 1904, and now became more so when caught out expanding their own influence in Tibet. Russia and France made representations to scale back anything that looked like the creation of a protectorate. Very few strategists had then realised that Russian Imperial power was already fatally weakened. Balfour had also run up a major budget deficit and sought to reduce his commitments to expenditure on military matters: he did not want to have to pay to station troops in Tibet. The change in British government had put critics of the Tibet Mission into power who were pleased to unwind aspects of the agreement48. The Tibetan treaty was re-visited with China in Shanghai in 1906. Britain was careful to refer to this as "Adhesion of China to the Tibet Convention" and to exclude any other state from the concessions granted. It was revisited again in 1907 as the St. Petersburg Convention between China, Britain and Russia. Tibet was not directly represented at either of these meetings49. The treaty's indemnity and the occupation of the Chumbi Valley were cancelled. Qing China had recently experienced the West's heavy reaction to the Boxer uprising, and presciently warned the Dalai Lama that he was heading towards conflagration, but found itself ignored and powerless during 1903-4 to act as anything but an ineffectual mediator. Amban Yu's frustrations showed through in his diaries, who write about "the worst Dalai Lama that had ever been seen", Tibetans as "the most foolish people", and when the Dalai Lama eventually requested help from Chinese troops he "bristled with anger" and point-blank refused50. 47 Hopkirk. 48 For example, Sir Henry Cotton, ex-Bengal Civil Service 1867-1902 wrote many critical letters to The Times, and was elected as a Liberal MP, 1906-10 Ref: OIOC Mss Eur D1202/3, 49 OIOC L/PS/10/148 2750/1908 50 Song Liming. When Manchu China invaded Tibet in 1910 there was no interference or objection raised by Britain. The Dalai Lama, who had returned to Tibet after the British left, fled again. This time he took refuge in Sikkim and then India, where he developed strong personal ties with the local British officers. As relationships developed several young Tibetans were sent to England for schooling and came back with motor cars and plans to electrify parts of the cities. The irony of 19th Century Tibetan isolation was that it was inspired by fears, sown by the earlier Chinese and Russian representatives, that the West would destroy their religion and culture. Yet by all accounts the effects of 1904 were relatively benign compared to the destruction wrought during the 1910 and 1950 Chinese invasions, and particularly during the Cultural Revolution. In the wake of the Hong Kong handover Chinese authorities have redefined the 1904 episode as the "Anti-British War" and set up exhibitions in "Anti-British Pavilions". They have accused the original British Mission of mass-looting, although it has been suggested that this is partly to cover up recent vandalism. Either way, examples of many of Tibet's key volumes and artefacts can only be seen now under controlled conditions in universities, libraries or private collections in the West. Additionally, the Tibet Mission was accompanied by botanists, zoologists and various other scientists who were looking to fill their greenhouses and museums with as many new species as they could find. A kiang (wild ass) and many plants found their way to London Zoo and Kew Gardens. Militarily, the Mission pioneered a number of new techniques of the British Imperial Army, but few lessons were learnt. Although they suffered from freezing and jams, this was one of the first uses of machine guns for long distance sniping. Initially they were used for rapid fire, but their consumption of ammunition became a hindrance to the force. At Gyantse and Karo La they were able to ration their fire through sniping and act as a reservoir of ammunition for the rest of the force to use in emergencies. The snow and the cold atmosphere ensured good visibility and the Maxims dominated open spaces during daylight The machine gun team commanders returned to Dehra Dun as advocates of machine gun warfare, but their officers were redeployed in other areas and their lessons forgotten until 1914. . The Tibetans, though armed with crude weapons, discovered effective defences using low walls and trenches. The infantry carried both the older Lee Metfield and the new Lee Enfield rifles. This was one of the first field deployments of the Lee Enfield, which was to become the standard weapon of British forces in both World Wars. It performed well out to 1100 yards and was respected by their users. Although lightweight artillery was important, the 7pdrs were soon relegated to firing star shell to deter night raiders. The 10pdrs fired shrapnel and "common" shell; the latter was surprisingly effective against the stone fortifications of Gyantse. The Mission was also notable for having fought the highest battles in the Empire, it also established the highest telegraph station and operated in some of the coldest climates, where water was often only available by breaking ice or boiling snow. The menagerie of animals used by the supply corps (who were augmented with officers and men from other units) at all altitudes was also unusual and inspired ad-hoc titles such as "Lt Pollock Morris of the Royal Donkey Corps", and "Captain Tillard, General of the Yak Division". The 1904 force required an enormous supply chain to operate at such altitudes, particularly as it was only able to source a little food and animal fodder locally. Part of Macdonald's challenge was to balance the size of the force against the capability to supply it over high altitudes. The timing of the advance to Lhasa was a calculated risk, as Macdonald had guessed the Tibetans would not attempt another strong resistance. If he had to build up stocks of ammunition to repeat an assault like that at Gyantse he reckoned it would take another two months, which would imply they would spend another winter at altitude. The campaign was unusual in the frequent recognition that was given to the supply and telegraph functions through awards and "Mentions in Dispatches". An earlier (ignored) British study had concluded that an invasion of Tibet could only be achieved by the southern route because the other entry points were too harsh or lacked grazing and indigenous supplies to support a sufficiently large force. Everything would have to be carried by the invader. By the time the mission had reached Tuna it seems they had realised any idea of a Russian threat through Tibet was infeasible. (Years later, during the 1950 Chinese invasion, the invading troops took all their food supplies from the land, which some observers calculate pushed the whole country to the brink of starvation.) Throughout the 19th century there was a rumour of the "curse" of the Forbidden City, and some of the Mission's "visitors" certainly suffered afterwards. The Gurkhas arrived back at Dehra Dun just before the 1905 earthquake devastated the area and caused many casualties in the regiment and surrounding district. Other officer's careers were badly damaged. Macdonald's conduct was criticised in several accounts. Yet the original task for which Brigadier General Macdonald was originally employed was generally well met; the advanced force was well supplied and able to operate without constraint, even carrying collapsible boats all the way to Lhasa in spite of the incredibly harsh conditions, and Younghusband was never more than a few days away from a telegraph line. His column carried each of Younghusband's 29 packing cases and personal camp bath over the 15,000' passes to Lhasa. (There was no criticism levelled at the logistics of this operation, while the war in South Africa had shown up a number of major logistical problems within the British Army, resulting in a public outcry and a major re-evaluation of defence policy and logistics through a Royal Commission of Inquiry under Lord Elgin in 1904.) He also had the foresight to recognise the need for mobile forces and supported the ad-hoc retraining of some Pioneers and Gurkhas as mounted infantry51. But junior officers and newspaper reporters reported him to be too old and cautious for the Mission. Younghusband privately criticised him as responsible for the mass-killing at Guru because of his confrontational, heavy handed approach52. At Gyantse the withdrawal of forces and artillery, and his selection of an overlooked defensive position, could have cost the Mission dearly, although the Mission's camp was rapidly and comprehensively improved by the Pioneers after he left. The supply route was often very vulnerable and poorly defended, but, fortunately for them, it was only attacked once. However, there did appear to be some disquiet - or jealousy within the military establishment that the lower-ranking "politicos" got the most public exposure and credit, and certainly Younghusband made several enemies amongst the senior military officers on that Mission and afterwards, who then saw it their duty to redress the balance whenever they had an opportunity to publicise the military aspects. London's embarrassment at the final deal meant that Younghusband received no official recognition until the King personally intervened to make sure he was knighted with a KCIE, but afterwards the British government managed to censure, side-line, and then ignore him. In spite of many attempts to contribute to the War Effort, he remained in England throughout WW1. He later turned his energies towards religion, mysticism, patriotic societies, and eventually became a catalyst for the first Everest mountaineering expeditions of the 1920s. 51 Ottley. Conventional wisdom dictated that Pioneers did not need to be trained in horsemanship as they would only ever be deployed with carts, even in the mountains of the NW Frontier. 52 French

Biography: Asylum Press and Indian Army, Army lists 1904 British Library, Manuscripts, Younghusband Papers British Library, Oriental and India Office Collection, LMIL & P&S Candler, Edmund & Newman, Henry, The unveiling of Lhasa 1905 French, Patrick, Younghusband 1994 Hadow, Arthur, The Britannia, Regimental Magazine of The Norfolk Regt Hopkirk, Peter. The Great Game1990, Trespassers on the Roof of the World 1982 Iggulden, H.A., To Lhasa with the Tibet Expedition c.1906 James, Lawrence, Raj 1997 Landon, Perceval, The opening of Tibet 1905 McKay, Alex, Tibet and her neighbours 2003 Ottley, W.J., With Mounted Infantry in Tibet 1906 Song Liming, Younghusband Expedition, p789 et al Tibetan Studies II, 6th IATS Conference 1992 The Times, London 1902-1904 Tower of London, Royal Fusiliers Regimental History Younghusband (The Stationery Office), The British Invasion of Tibet 1904

Ref: By Colin Fenn London 2008

Alston Rowland Ernest of 69 Ecclestone Square Middlesex died 3 June 1904 at Chumbi Sikkim India Administration London 21 Aug 1905 to Francis George Alston Lt Scots Guards effects £1848 1s 6d. National Probate Calendar.

Other Records Other Records

1. Census: England, 3 Apr 1881, 69 Eccleston Sq MDX. Rowland is recorded as a son aged 6 a scholar born St George Hanover Sq

2. Rowland Ernest Alston: House list of Mr Donkin of Rugby School, Jan 1890.

Rowland as young man.

3. Census: England, 5 Apr 1891, 69 Eccleston Sq St George Hanover Sq LND. Rowland is recorded as a son single aged 16 a scholar born St George Hanover Sq LND

4. Capt Rowland Ernest Alston: Died Chumbi Valley Tibet, 28 May 1904.

From: Colin Fenn

Sent: Tuesday, 26 August 2008 6:37 a.m.

To: Edward Fenn

Subject: Re: R E Alston

Hello Edward,

Great to hear from you, all is well over here.

I'm just catching up on the last week's mail hence the tardy reply!!

I've been keeping quite busy recently, so I'm only getting intermittent snatches of time to deal with FH. However, partly inspired by your grand oeuvre, I am planning to pull together an illustrated family report and test out the self-publishing capabilities of Lulu.com later in the year.

Now, regarding this Alston chap, I saw 3 references to him in the book "Duel in the Snows" by Charles Allen, describing the Anglo-Indian invasion of Tibet in 1903-4. I looked into the topic as my wife's ancestor was also in the expedition. He notes Lt R E Alston as a member of the 1st Bn, Royal Fusiliers. The account relies on letters sent by Lt Thomas de B Carey of the Royal Fusiliers to his wife, held in the Royal Fusiliers museum at the Tower of London.

P.182: Alston is first mentioned in the book by Carey who talks of the battalion reaching the base at Gnatong at 11,700 ft, meeting the 4th Gurkhas and having a "tip-top lunch". Dunning of the same regiment

wrote: "To see me you would think I was an esquimaux. . . . . coat made of a sheepskin, thick boots up to the knees, a cap to cover the head and face, finished up with a pair of blue spectacles."

Lt Carey wrote: "No men sick up to date. . . . . All officers very fit except Alston, who complains of cold & a very bad head. I expect it is mountain sickness combined with a chill"

P183: The regiment crossed the Jelep La, en-route to the fighting that had just broken out at Gyanste. Lt Carey again: "I regret to write that towards dusk my company commander, Lt Alston, was carried in on a stretcher, having had to give up before reaching the summit of the Jelap, owing to his heart. Poor fellow, he looked very blue in the face when I saw him and I fear he will not last long" The pass took them 14,390 ft above sea level.

They then passed through Yatung and camped at Chumbi village.

Carey: "I can hear the bagpipes of the Gurkhas playing all day, and they sound very sweet amongst these gigantic hills. They are guarding Brigadier General Macdonald's residence, about three-quarters of a mike from our camp. . . . . We buried poor Lieut Alston who died this morning of pneumonia"

"Alston and Carey had shared quarters: 'He was a very good chap' mourned the latter. 'I have never known him to be ill before'. In the Anglo-Indian custom, Alston was buried within hours of his death, with Carey commanding the party that fired a salute over his grave, in the presence of the General and all his staff."

P:184: Over the next few days the Fusiliers were joined in New Chumbi by the 40th Pathans. "As the men of Alston's company were erecting a stone wall round his grave, they heard the blowing of innumerable trumpets as saw a long procession of approaching", the ruler of Bhutan Ugyen Wangchuk, known as the Tongsa Penlop.

There is also a photograph opposite page 210 - I reproduce it here though it is of fairly poor quality. It was taken just a few days before his death. Allen cites it coming from the Royal Geographical Society collection, but gives it no other reference.

See: 1st. BATTALION ROYAL FUSILIERS - THE TIBET MEDAL ROLL https://www.fusiliermuseumlondon.org/download?id=12393

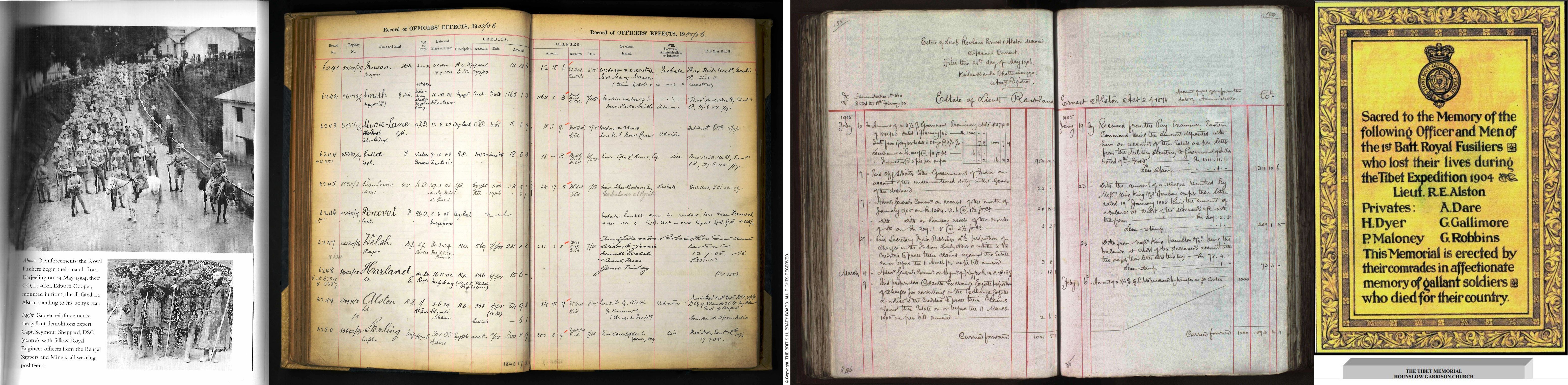

First image:

Reinforcements, the Royal Fusiliers begin their march from Darjeeling on 24 May 1904, their CO, Lt Col Edward Cooper, mounted in front, the ill-fated Lt Alston standing to his pony's rear.

Below.

Sapper reinforcements, the gallent demolitions expert Capt Seymour Sheppard, DSO, (centre) with fellow Royal Engineers Officers from the Bengal Sappers & Miners, all wearing poshteens.

|

Cause of his death was pneumonia.

Cause of his death was pneumonia.