Rev Adrian Henry Timothy Knottesford FORTESCUE [14697]

- Born: 14 Jan 1874, Hampstead MDX

- Died: 11 Feb 1923, St Andrew's Hospital Dollis Hill London aged 49

- Buried: Letchworth HRT

Cause of his death was cancer. Cause of his death was cancer.

General Notes: General Notes:

Rev. Adrian Henry Fortescue was a distinguished scholar and writer, primarily about Roman Catholic liturgy and the Eastern churches. Amazon records a large number of books written by him. Perhaps the best known is The Ceremonies of the Roman Rite Described, which is still in print, and in something like its fifteenth edition. I think it is probably regarded as the definitive treatment of how Roman Catholic priests were supposed to carry out the mass and other services, before Vatican II completely changed the rules! There is a recent biography of him: Aidan Nichol OP, The Latin Clerk: The Life, Works and Travels of Adrian Fortescue, The Lutterworth Press, Cambridge, 2011. Among other things, this biography does state Adrian's birth date as the 14th January, 1874.

Ref: Dr S Lapidge 2014

The Latin Clerk: The Life, Work, and Travels of Adrian Fortescue (review)

Anthony Dragani

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Adrian Fortescue (1874-1923), a priest of the Archdiocese of Westminster, was a defining figure in English Catholicism. A prolific author and speaker, Fortescue's writings on liturgy and Eastern Christianity helped to shape public perceptions of both subjects. Aidan Nichols's biography, The Latin Clerk: The Life, Work, and Travels of Adrian Fortescue, provides a glimpse into the innermost life of the man as well as his scholarship. It details Fortescue's achievements as a liturgist, orientalist, historian, and pastor.

The book starts by chronicling Fortescue's formative years, with an emphasis on those events that molded his outlook. It tells of his father, prominent Anglican clergyman Edward Bowles Knottesford Fortescue, who made the difficult decision to convert to Roman Catholicism before Adrian's birth, and how this choice affected the future of his family. Forever conscious of his status as a member of England's Catholic minority, Fortescue sought to defend his faith against Anglican critics. As a result, he became renowned as an apologist for the Catholic faith and a defender of the papacy.

The focus then shifts to Fortescue's preoccupation with Eastern Christianity. As a young man, Fortescue was greatly influenced by Greek Catholic monks in Grottaferrata, Italy. He was so captivated by the beauty of their liturgy and spirituality that he decided to dedicate himself to studying the Christian East. This led Fortescue to disguise himself as an Arab and to travel extensively throughout the Levant. During his adventures, he became familiar with the ancient churches of that region and occasionally defended himself from robbers in shootouts.

Nichols's book presents an overview of Fortescue's writings on Eastern Christianity and highlights recurring themes found within them. It paints Fortescue as an ecumenical pioneer who, despite occasional polemics, worked to build understanding and unity between Western and Eastern Christians. It also touches on his unfulfilled desire to transfer to the Melkite Church.

Fortescue's liturgical scholarship also is explored in detail. Among English-speaking Catholics, Fortescue was primarily known as an expert on ritual and rubrics. It is ironic that he loathed addressing these subjects. Nichols lays out the theological reasoning behind Fortescue's liturgical perspective as well as his practices as a pastor.

The most fascinating aspect of this biography is how it chronicles Fortescue's emotional turmoil during Pius X's antimodernist crusade. It provides a portrait of a dark time in Catholic history, during which theologically orthodox priests such as Fortescue fell under suspicion simply for being too intellectual. It was painful for Fortescue, who had defended the papacy so vigorously, to watch the See of Peter become a perpetrator of indiscriminate oppression. Fortescue was so disturbed by Pius's actions that he contemplated leaving the priesthood.

This biography is both enlightening and entertaining. It illuminates Fortescue's key insights, many of which remain just as true today as they were during his lifetime. But it also paints a vivid picture of Fortescue and his greatness. From reading Nichols's book, it becomes clear that Fortescue was a brilliant, eccentric, and colorful character. The account of his battle with cancer and premature death is surprisingly moving. Overall, The Latin Clerk does an impressive job of capturing both the essence of the man and a particular epoch in Catholic history.

Copyright © 2012 The Catholic University of America Press

Project MUSE® - View Citation

ADRIAN FORTESCUE CLERIC OF THE ROMAN RITE

A BIOGRAPHY BY

JOHN R. MCCARTHY, Ph.D.

Note: our copy of Fr McCarthy's biography is not paginated, and the text begins on the left-hand side of a two-page spread, rather than the right-hand side, so that if it were paginated, it would seem to be 'wrong'. My extracts begin with the first section of the book, called 'THE FAMILY', at the top of the right-hand page. For convenience, I will refer to this as 'page 3'.

THE FAMILY

Fr McCarthy begins by referring to the book A History of the Family of Fortescue in All its Branches (1880), and at the top of 'page 3' he comments:

. . . It [sc. the book] also contains Edward Bowles Knottesford Fortescue acknowledged to be "the senior member of the senior branch" and his children, including Adrian Henry Knottesford Fortescue.

Edward's father was Francis Fortescue, born in 1772. In 1786, at age 14, on the eve of his going to Eton, Francis was set the task of writing his autobiography. He mentions visiting his godfather Mr Knottesford, at Bridgetown and going to a Quaker school. "On the 19th of May, 1781," he wrote, "my papa Knottesford died. He left me his estate and I am to change my name when I am of age."

Francis Fortescue went to Eton and on to Queens College, Oxford and became Fortescue Knottesford on April 4, 1793. That the Knottesford inheritance made him a rich man is indicated by the fact that when he took his M.A. in 1789, it was as a "Grand Compounder." This was a distinction reserved for candidates who had an income of £300 per year on their own. It entitled the possessor to wear a red gown and to have a special procession on the day he took the degree. It also required the payment of higher fees than those required of poorer graduates. Originally almost an exclusive prerogative of the aristocracy, its occurrence increased with the increased spread of money at the end of the eighteenth century. It fell into disuse by 1817 and was officially abolished in 1855.

Francis Fortescue Knottesford took Holy Orders in the Church of England and went as curate at Hadleigh in Suffolk. His parish church was St. Mary the Virgin, a Gothic structure of the latter half of the fourteenth

('page 4')

Century made famous in a painting by the artist Constable. There was a chapel in the parish at Nayland where Knottesford was listed as curate in 1813.

Graduation, ordination and a curacy were three important steps in the life of a young man of that time, place and class. All that was needed was marriage, and that, too, was soon to come about. The young lady in question was Maria, daughter of the Rev. George Downing. The Downing family has left some permanent traces on the face of England: The London street made famous by the residence of the Prime Minister is one, Downing College at Cambridge is another.

The young couple settled at Stoke-by-Nayland and produced five children, the youngest being Edward Bowles born on April 26, 1816. A letter survives written by the new father to his oldest son:

My dear boy will, I am sure, be delighted to hear that he has another brother and that his dear mamma is as well as possible. This little stranger made his appearance in the world rather unexpectedly on Saturday night.

He is a very fine little fellow and is to be called Edward Bowles. Mamma was going with me to Hadleigh on Sunday had she not been prevented a few hours before. It was indeed a great chance that he was not born there. As I was engaged to perform the duty there, I was obliged to go, but had the great satisfaction of leaving mamma quite well and carrying the agreeable and surprising news to grandmamma.

I went in a Post chaise and took Fanny and Maria with me, as they had been engaged to go and I did not want to disappoint them.

They were very much pleased with their ride.

('page 5')

ADRIAN'S FATHER

Adrian Fortescue's father, Edward Bowles Knottesford Fortescue, was born on April 26, 1816 at Stoke-by-Nyland [sic] in Suffolk where his father, Francis, was curate at the local church. He was seven years old when he moved with his parents, brother and two sisters, to the family estate in County Warwick. His father had inherited the Warwick property in 1793 and there seems no explanation for the delay in this move.

The house to which Edward moved with his family in 1823 was a large mansion just across the Clopton bridge from Stratford-on-Avon. At that time it was in the parish of Alveston but for all practical purposes was a part of Stratford-on-Avon and in time would be incorporated into that borough. In 1823, however, the shrines of the Bard of Avon had not yet become the chief local industry. Stratford-on-Avon was just another small market town entering the modern age with the construction of the Stratford-on-Avon Canal and the coach service which ran three times a week to London.

[Alveston Manor became a Trust House Hotel under the name Alveston Manor Hotel. A brochure advertising the hotel suggested that "A Midsummer Night's Dream" was first performed on the Manor lawn.]

As soon as the family was establish [sic] at Alveston Francis took on the care of the parish of Billesley, an isolated place about five miles from his home. It had once been a thriving village, but that was in the Middle Ages. For some reason, possibly the Black Death, it depopulated, and by the time Francis Knottesford began his ministry it

('page 6')

consisted of five houses and about thirty persons. William Hutton in his book Highways and Byways in Shakespeare's' [sic] Country (1914) has preserved a colourful description of a typical Knottesford Sunday.

On Sundays at Alveston the family coach came across to the front door. The clergy and the whole household found places in it or outside, and drove six miles to Billesley, where morning service took place at 11 o'clock.

After morning service Francis and his family retired to one of the pews for dinner. The footman laid the cloth on a seat-the pew contained a firegrate-and the cold dinner, brought over in the coach, was set out. The rector, with the noble English tradition of observing the Sunday rest for his servants so far as possible, for a long time refused hospitality on Sunday. He would give no, or at least the minimum of, trouble to any servants on Sunday. He subsequently yielded so far as to accept the use of a parlor from a friend leading to an adjacent garden. After dinner children retired to the churchyard to play, the rector rested in the pew, the servants elsewhere finished the dinner. At 3 o'clock came evening prayers and sermon, after which the whole family mounted the coach and drove six miles home.

How well one can picture the old gentleman in old-fashioned black knee-breeches, black silk stockings, and silver-buckled shoes. The old gentleman's surplice, no doubt, reached to his feet, and so he needed no cassock, but he probably wore one.

This depiction of Francis in the 18th century dress is not the fancy of a writer. Family photographs survive showing him with his family just so attired. His wife was reported to have said that she didn't know the natural color of his hair because the powder from the wigs had altered it. It is also reported that visitors were much impressed by his manners which matched the style of his clothes.

('page 7')

All was not joy and tranquillity at Alveston Manor House. Three years after the move from Suffolk the family was saddened by the death of the second son, twelve-year old George Downing. Little is known of the lad's death except that he was buried in the churchyard at Billesley. Whether or not he died while away at school, as did his older brother, is not certain. What is certain is that Francis determined that his youngest and only remaining son, Edward, already sickly, would be tutored at home. The tutor was the Rev. William Meade, who took his B.A. at Wadham College, Oxford in 1829. When Edward was registered at Wadham College it was noted that he was "preparing with Mr. Meade of Alveston." In view of his father's views on religious practice as well as his own subsequent history, it can only be the influence of Meade that led to Edward's matriculation at Wadham (June 5, 1834) for the college was then at the height of its reputation as the Evangelical enclave of the University with its Warden, "Big Ben" Symons, the "prop and pillar" of that school of thought. It was in that spirit at that time that evening service was transferred to the afternoon, supposedly to prevent the students from going to hear John Henry Newman whose sermons were attracting increasingly large crowds of the University's young men.

Newman himself was later to write that when Edward Fortescue was at Wadham, "people could not make him out, he lived by himself."

In 1838 Edward took his B.A. and returned home to prepare for the two events that were the touchstones in

('page 8')

the life of a young man of his station: his marriage and his ordination to the priesthood of the Church of England.

There is no surviving record, if indeed it was ever recorded, how Edward met Frances Ann Spooner. Fanny, as she was known in her family, was one of ten children, the fourth of five daughters, of William Spooner and Anna Maria Sidney O'Brian of Elmdon, a Warwickshire village outside of Birmingham.

William Spooner was ordained in 1801 and was immediately nominated to the family living as rector of Elmdon. In 1827 he was appointed Archdeacon.

Francis Fortescue Knottesford performed the marriage ceremony of his son and the Archdeacon's daughter in the family parish church at Elmdon, 15 Nov. 1838. This marriage not only brought Edward seven children but a host of connections to the ecclesiastical and political life of England in the 19th century. Fanny's aunt Barbara was the wife of William Wilberforce, MP, the eminent abolitionist. Fanny's sister Catherine was to marry Archibald Tait (1811 - 1882) who became Archbishop of Canterbury. Fanny's cousin Samuel Wilberforce, later bishop of Oxford and Winchester, was married to Emily Sargent whose sister Caroline was the wife of the future Cardinal Manning. And not to be overlooked is the brother-in-law, the Rev. William Archibald Spooner, Warden of New College, Oxford whose habit of transposing the letters or sounds of words ("crushing blow" became "blushing crow") popularized the word "Metathesis" as "Spoonerism."

('page 9')

Marital bliss and social conviviality were in abundance at Alveston Manor, but never so much as to interfere with the religious obligations of the family. Edward was ordained deacon by the Lord Bishop of Worcester on June 9, 1838 and priested in the following year. His title was as curate at Billesley, a position provided for by his father.

('page 10')

WILMCOTE

Not far from Billesley is a place called Wilmcote, a place of ancient lineage, as its name implies ("cote of Wilmund's people"). While never important enough to be a parish, a record of 1228 says there was a chapel of Aston Cantlow there. In 1481 its advowson (the right to name the holder of a church benefice) was given to the Guild of the Holy Cross at Stratford. In 1638 a cottage lease referred to "the chapel" and a field nearby was known as "chapel close." There is a later listing referring to Wilmcote as a demolished chapel attached to Aston Cantlow with its dedication to St Mary Magdalen.

After lying fallow for so long, Wilmcot began to come alive in the early nineteenth century because of its rock quarries and the railroad and canal building that was taking place around it. As early as 1803 the Independents, or Congregationalists as they were known, began to preach the Gospel in Wilmcote, serving the place as a mission of Stratford-on-Avon. The expansion of work in the place made it something of a boom town. The historian of the Independents called it a "dark and notoriously ungodly place, a sink of iniquity where the quarry hands would get in a cask of ale on Saturdays and sit down to finish it, thus damning their souls and ruining their families at the same time." In 1840 the Stratford-on-Avon Village and Town Mission, established to uplift the villages of the surrounding area, was distributing religious tracts in Wilmcot and encouraging people to send their children to Sabbath School.

('page 11')

As there was no church of the Establishment between Billesley and Aston Cantlow, and considering the inroads of "Dissenters," Wilmcot was an ideal place to establish a chapel of ease. The little church of St Andrew stands in Wilmcote as a tangible monument to the religious dedication of the Knottesford Fortescues. It has a sister church in Letchworth built by Edward's youngest son, Adrian. The distance between the two is not long in miles, or even time, but the twists in the road make it a complex, and even difficult, journey.

The project at Wilmcote must have been long on the mind of Francis, not just as rector of Billesley who was making up for the negligence of the incumbent at Aston Cantlow, but also as an ideal way for him to keep his beloved son Edward close by his side in his latter days. To this end Francis bought the advowson of Aston Cantlow. The advowson was the right to nominate the next vicar of the parish. Because the trading of advowsons was a matter of private property and therefore a private matter, no record was kept of the transactions except to notify the bishop of the fact. When the incumbent died, in 1846, Francis Knottesford made the next presentation. It was not Edward.

The actual work on the church at Wilmcote got under way sometime in the spring of 1840. There were delays due to lack of funds and changes in plans, so it was not until Nov. 11, 1841 that the church was consecrated.

This was not a simple chapel such as the Independents might build. It was an early example of what came to be called "Gothic Revival." For a long time it was thought

('page 12')

that William Butterfield, a name second only to Pugin in Gothic revival architecture, was the architect. He was definitely responsible for the school and parsonage at Wilmcote, but a letter of Maria Fortescue mentions only the name of Harvey Eginton as architect. His buildings, too, resembled those of the thirteenth century.

THE OXFORD MOVEMENT

The Roman Catholic Church in England can be considered like a three-legged stool. First are those who proudly claim an unbroken loyalty to Roman Catholicism back beyond the Reformation. Second there are the Irish and immigrants from Europe and around the Empire. It is sometimes said that if you scratch almost any Catholic in England you will find an Irishman underneath. The census numbers indicate that between 1800 and 1850 Catholics increased from 100,000 to 750,000, mostly by immigration from Ireland. Thirdly there are the converts from the Established Church and Protestant denominations. It must not be thought that these legs are of equal size. The Established Church still has the numbers, positions and money but not to the extent that it did in Edward's time. All kinds of persecution and legal disability reduced the number of traditional Catholics, but never eliminated them. And while being a "Papist" was an evil and even dangerous thing, being "Catholic" took on a different meaning. There is a long tradition in British history of an effort to hold on to the Catholic Faith without the Pope. In volume II of his history of The Churches in England from Elizabeth I to Elizabeth II (1997), Kenneth Hylson-Smith recounts (p. 215) the case of one Charles

('page 13')

Daubeny writing in 1798 that the true church must have a duly commissioned ministry deriving its authority in direct line from the apostles. He taught that the priesthood was a divine institution and that the sacraments were the "seals of the divine covenant." He was part of a mixed tradition that extends from the Reformation to modern day Anglo-Catholicism. Another name in this tradition is William Jones, vicar of Nayland. This is the same Nayland where Francis Fortescue Knottesford went as curate and where his son Edward was born. When Adrian wrote to his cousin "our branch remained loyal to their King and Faith," it was in this context that he spoke. While he never examined this issue directly, he did so peripherally through the Eastern Churches whose histories are one long saga of trying to hold on to the Faith without the Pope. In the wake of the ecumenical movement it is acknowledged that the Faith exists, albeit incomplete, without the Pope. Persons now joining the Church of Rome are not "converts" but "embracing the fullness of Revelation."

All of these "semi-Catholics," (the term is mine) belonged to The Established Church and contributed to and were a part of a number of incidents that came to be best known as "The Oxford Movement" although they were also known as "Tractarians" and "Puseyites." There are many books and theories about how and when it all started, "Tracts for the Times" produced by Oxford dons, notably John Henry Newman, were a main step in the movement. Their thrust was to demonstrate the Catholic and Apostolic nature of the Church of England.

('page 14')

The program was not just a question of theological debate but also of matters of ritual and practice.

Edward built his church at Wilmcote in the Tractarian spirit and is credited with introducing eucharistic vestments (the chasuble) and retreats for priests. That all this could go on under the eye of his father is best understood from a letter written in August, 1844. Sometime earlier that year Edward became seriously ill, prompting Newman to write to Anne Mozley:

. . .We have been made very sad by the suddenly hopeless state of a person probably you never heard of-Mr Fortescue, a clergyman who married William Spooner's sister, and a great friend of Henry Wilberforce. He is of a nonjuring family, and was taught secretly Catholic doctrine and practice from a child. From a child, I have heard, he has gone to confession. When at Wadham people could not make him out, he lived by himself. After a while, to his surprise, he found the things he had been taught to keep secret as by a disciplina arcani common talk. He had had most wonderful influence in his neighbourhood, more than anyone in the Church, I suppose. He is suddenly found to be dying of consumption, his left lung being almost gone. They speak as if a few weeks would bring matters to a close.

Edward recovered and was back at work at Wilmcote in the late summer or early fall of 1845 and seems immediately to have immersed himself in the project of building a schoolhouse. Certainly one of the reasons for building the school was to keep Edward busy, a goal undoubtedly emanating from Francis Knottesford who must have been deeply concerned about his son's joining

('page 15')

the Roman Church. Edward may have tried to make some decisions in the matter during his illness and now the possibility grew daily in the wake of Newman's "going over to Rome" on October 9, 1845. A long letter from Edward's mother-in-law to her daughter Catherine, now Mrs. Tait, written sometime in September or October, 1846, conveys the family concern for the matter.

But dear, I have deep anxiety as respects Fanny and Edward. May God grant our fear may not be realized, but I do fear Edward is on the very brink of going as so many have done. I found him in a state of much anxiety and suspense as the time is now come when he must make up his mind to join those who have left our church or to make some final announcement to remain at Wilmcot. He says he could not take the living and he could only remain at Wilmcote by the living being given to some one who would let him remain as curate. His friends are doing all they can to influence him to remain, Archdeacon Manning most strongly. I think he will go next week to Archdeacon Manning. He did not speak either to Papa or me on the subject, but seemed in good spirits and showed us all his new school is most complete and the spot for the house. Fan and all his friends are in prayer for him this week and she is sure he will be guided aright. You may suppose with what anxiety we shall wait the result but I think it better, except by yourself and Archy, not to speak of it, as this cloud may again pass away. In writing to Fan do not say I have mentioned it. It has come so unexpectedly on me that I cannot contemplate it at present.

('page 16')

Somehow the news of what was happening reached Newman, who was preparing for the Roman Catholic priesthood in Rome, so that he wrote to Henry Wilberforce in early December that "the report here is that Fortescue is near moving." Newman was premature. Edward did not join the Church of Rome at this time, nor in 1851 when Archdeacon Manning, his mentor, joined the Church of Rome. He also did not stay at Wilmcote, but went to the Scottish Episcopal Church to become Dean at the Cathedral in Perth. His father had all the arguments for an apostolic but non-Roman church in England, and if they were weakened in the current course of events, the Church in Scotland was even more venerable, more loyal to the sacraments, and more independent of the civil power. The Established Church in Scotland was Presbyterian. What was left from the days before the Reformation were a handful of Roman Catholics in the Highlands and the "thin on the ground" Episcopalians Edward was now going north to serve.

ST NINIAN'S CATHEDRAL

The Episcopal Church in Scotland which drew Edward to Perth claimed to be the true custodian of the Catholic and Apostolic tradition in that country and purified of Roman errors at the Reformation, it also stood firm against the corruptions of Presbyterianism.

Scotland was a separate kingdom until 1603 when the King of Scotland, James VI, ascended the English throne as James I. This union of the countries in the person of the sovereign led to the Act of Union in 1707. This in turn led to the presumption that a monarch could be an Episcopalian in England and a Presbyterian in Scotland.

('page 17')

The rebellions of 1715 and 1745 were the result of this confusion and their suppression brought penal laws into effect against Scottish Episcopalians.

When a more enlightened age abolished penal laws and Scottish Episcopalians began to come into public light there grew a movement called "The Cathedral Scheme" which proposed to build a Cathedral at Perth to revive not just the spirit but also the presence of a fragmented and more or less hidden congregation. Butterfield was the architect, the first stone was laid September 15, 1849 and a truncated version of the original plan was consecrated with great solemnity on December 11, 1850. These ceremonies were under the guidance of Edward. A letter from his father to Routh at Magdalen College, Oxford explains much of what was happening to and in his son's life.

I flatter myself you will be pleased to hear that my son is now Dean of the Cathedral Church of Perth to which honorable office he was elected by the Canons on the 11th ult. after the Consecration of the Church (the whole ceremonial of which was entrusted to his management) thru the powerful recommendations of Lord Forbes and the Honorable Mr Boyle, Banker & Heir to the Earl of Glasgow, the chief promoters and contributors to the building and institution to which I believe you were a Benefactor. On the following day Edward preached. He is a powerful preacher, which was one very necessary qualification for the office in Scotland. I remember the great interest you have always taken in the Episcopal Church of Scotland which yet remains a pure branch of the Catholic Church of Christ and will probably offer a

('page 18')

refuge to many who may feel conscientiously obliged to resign their preferments. It remains the most powerful bulwark and most effective testimony against the errors and corruptions of the Church of Rome. The appointment to which I principally refer appears to be so remarkable a leading of Providence under existing circumstances as it would be heedless to disregard. We therefore, notwithstanding the distance, readily acquiesced in it and I am sure you will add your prayers. His services will be as free & voluntary as they have been at Wilmcote where he has built a church, house, and school and performed the duties of it without any remuneration whatever, nor will he have much more, if any, from his new preferment at present. I must now assist him to enable him to discharge his new labors at Perth.

The ceremonies of the Consecration of St Ninian's lasted for a week and were described in a number of places. The Perthshire Constitutional began with a background paragraph on the Scottish Episcopal Church.

The Scottish Episcopalian Church has never appeared to merit anything except contempt from us during the last fifty or sixty years. It has been gradually dwindling down to a puny sect, whose ministers have been noted for little but the holding of opinions of the most bigoted nature, without having the courage or the energy to propagate them. It has been till of late only conspicuous, as a body, for possessing the meanest edifices and the worst paid clergy of any denomination. But looking at the magnificent commencement of the Cathedral in Athole Street, and its College adjoining, we are free to confess that a step has been made to obliterate the stigma long cleaving to the Scottish Episcopalians.

('page 19')

It was not just the pull to Rome that ended Edward's time at Wilmcot, but a series of difficulties about his "extreme" ritualism. He was not long in Perth before he was put in another difficult position. On October 3, 1852 the bishop of the diocese died and it became the duty of the clergy to elect his successor. Charles Wordsworth became the new bishop by voting for himself. He did not recognize the Cathedral as such and its clergy took no part in his election. Objections to the Cathedral were not only due to the historic hostility in the community toward Episcopalians, but also toward a ritual "suitable amongst an impassioned people, such as the French or the Italians." Nothing, it was said, was more harmful to the Church in Scottish Society than "anything which even seems to partake of the ritualism of Rome." Of course Edward was the prime mover toward the "ritualism of Rome," and his son Adrian would become the English speaking world's prime teacher of that ritual.

In 1855 the last child to be born of Edward and Fanny was named Charles Ninian. He died at seven months and is buried in the New Cemetery at Perth. His mother, who died thirteen years later, is buried by his side.

Another view of the world of the Perth Cathedral was published in the October, 1852, issue of Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine. The article, entitled "Church Parties," contained the following under the heading "Tractarians:"

Another favoured haunt of the sect is among the Episcopalian Non-conformists of Scotland. These descendants of the Non-jurors, whose worship was, within living memory, subjected to the

('page 20')

Penalties of the Law, still retain the spirit and temper, as well as the Liturgy, of Laud. Their bishops are elected solely by the clergy, and the clergy of each diocese average from ten to twenty in number (The three smallest Scotch Dioceses contained in 1852 only 13 clergy apiece. The other day there was a fierce contest for the election of "the Bishop of St Andrews." Sixteen clergy were brought to the poll, 8 on one side and 8 on the other, and the successful candidate, Mr Wordsworth, was so far from affecting the nolo episcopari that he gave a casting vote for himself. It is but justice to say that he deserved a much higher honour than that thus obtained, being a man of real learning, and one who has done much for the cause of Christian education.) It is natural that these functionaries should make up for their want of temporal importance by exalting their spiritual dignity. Their communion affords a refuge to those who, though disgusted with the Protestantism of the Church of England, cannot quite resolve to join the Church of Rome. (We find from the official accounts that half the clergy now officiating as Episcopalian Non-conformists in Scotland were ordained in the English Church.) Several of these seceders have been elected to Scotch Bishoprics, and amuse themselves harmlessly with playing at prelacy. For here they can lord it safely over their tiny flocks, and can wield the power of the keys without setting the country in a flame.

Francis Fortescue Knottesford died on May 31, 1859. The funeral that followed was a phenomenon for its time and the newspaper reports that covered it were even more so. The four page provincial newspapers of the time were not given to obituaries in the same way as their descendants of a later age would be. Generally a death notice was enough. Not so in the case of Mr Knottesford who was accorded many personal accolades and a full coverage of the funeral.

The death of the venerable and highly esteemed gentleman whose honoured name heads this paragraph is

('page 21')

a great calamity to the area. The Established Church lost a rich ornament, a zealous advocate. But it was the poor, the needy, the desolate, and the afflicted who had the most cause to lament the removal of a man who was always a valued friend and munificent benefactor.

On the day of the funeral from noon until three o-clock almost every place of business in Stratford-upon-Avon was closed. Clusters of people gathered along the route numbering thousands, one of the most affecting tributes to the departed ever witnessed in the town and neighbourhood of Stratford-upon-Avon.

The funeral cortege went from Alveston Manor House to the place of burial in the church of Billesley. There were five mourning coaches followed by five private carriages, the first being Mr Knottesford's own carriage with two of his old men servants. The united choirs of Billesley and Wilmcote chanted a portion of the funeral service.

Whatever restraints Edward's respect for his father may have had on him, his passing made no immediate change in his life. He resumed his duties in Perth and carried them out through the "going over to Rome" of his old mentor Henry Manning in 1865, and the death of his wife in 1868.

The year 1870 was one of many changes in the world and no less so in the life of Edward Fortescue. The year of mourning for his deceased wife had ended and the two children who had remained closest to him were ready to make their own paths in life. The oldest, Edward Francis, married Alicia Margaretta Tyrwhite, daughter of

('page 22)

the rector of St Mary Magdalene's at Oxford. The only daughter, Mary, married George Augustus Macirone, a civil servant at the Admiralty. The three sons who had gravitated to Archbishop Tait were also getting settled, Lawrence in the Marines, and subsequently to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, George as an assistant in the library of the British Museum, and eventually The Keeper of Printed Books, and Vincent at Cambridge, eventually a clergyman of the Church of England. Of his fourth son, John, little is known beyond a picture of his burial place in Jamaica where he died 13 Jan., 1874. Then on July 5th, 1871 Edward Knottesford Fortescue resigned as Provost of St Ninian's Cathedral.

CHURCH UNITY

For Edward Fortescue and his tradition there was no question about the Catholic continuity of the Church of England and the Scottish Episcopal Church. Their problem was the Church of Rome and its non-English allies - a problem that seemed nearer to solution as knowledge of the position of the Orthodox and Eastern Churches became more widespread, especially through the work of John Mason Neale (1793 - 1876).

Edward was certainly in England during the first days of September, 1857, as a result of the death and funeral of his father-in-law Archdeacon Spooner. On the morning of September 8, the feast of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin, small groups of Anglicans, Greek Orthodox and Roman Catholics met at their respective altars for prayers for unity. At noon they met at St Clement Danes in the Strand, for a meeting that was to be the formation

('page 23')

session of the Association for Promoting the Unity of Christendom (A.P.U.C.).

The chief promoters of this meeting were Ambrose Phillipps de Lisle and Augustus Pugin on the Roman Catholic side; The Reverend Frederick George Lee and Alexander Penrose Forbes, Bishop of Brechin, on the Anglican side. De Lisle was offered the Presidency, but declined, whereupon Edward was elected to the chair, a position he was to hold for the next fourteen years. The object of the Association was the daily prayer of its members for the union of the churches. At its peak it claimed over 7000 members and was responsible for some ecumenical publications and meetings, especially an annual gathering commemorating its foundation. Conspicuous by their absence from its membership rolls were the bishops of the Church of England, and in time the A.P.U.C. was condemned by Rome for Roman Catholic participation.

In the same spirit in 1863 at the residence of the Reverend W. Denton in London, representatives of the four branches of the Anglican Church organized themselves into the Eastern Church Association. The object of the group was not to propose schemes of union but to inform the English people about the Eastern Churches and to make the Eastern Churches more aware of the Anglican Church. In the first report of the association Edward was listed as a member of the standing committee: The Honourable George F. Boyle was its chairman. Although little is known of Edward's involvement with the association beyond his

('page 24')

Membership, both his son Edward Francis and his son-in-law were actively involved.

NEW LIFE NEW WIFE

On July 17, 1871 Edward Knottesford Fortescue married Gertrude Robins at St Mary's parish church, Marylebone, with the Reverend Albert S.W. Young presiding. The witnesses were Edward's son-in-law, George A. Macirone, and Gertrude's mother, Caroline G. Robins. The marriage was followed by a European honeymoon. Family tradition has it that the couple were together in St Peter's in Rome at this time and each simultaneously said to the other that he wanted to join the Church of Rome.

The fact is that they returned to London and entered the Roman Catholic Church on Easter Saturday, March 30, 1872. Edward's sons Lawrence and Vincent must have been on hand for the occasion because the next day, Easter Sunday, they were with the Taits and the Archbishop recorded in his diary: "The Fortescue boys had the account of their father's rebaptism and reception into the Romish Church yesterday."

By becoming a Roman Catholic Edward not only lost social prestige and probably a certain amount of family affection, but also his clerical status.

In the Roman church with its celibate clergy the only place for a married man was among the laity. After a lifetime as a cleric, this must have been the most difficult part of Edward's conversion. The Dominicans at Haverstock Hill tried to ease the burden as much as they could by allowing him to read the Epistle at Mass, a

('page 25')

custom from ancient times which has been revived since Vatican II, but was almost unheard of at the end of the nineteenth century.

But the dedicated Edward Fortescue, who would not play the role of a rich man's son when he graduated from Oxford, or that of a country gentleman when his father died, was not content to be a retired layman when he became a Roman Catholic. He turned to the church's other self, the school.

The newly married couple went to live at Rose Villa, Eden Grove, Holloway, (London) in "a picturesque old house with a large garden." The house was next door to the Sacred Heart School and only a few steps from the church. Edward not only had charge of the school but also taught the Latin and Greek classes. A local paper of the time, North Metropolitan and Holloway Press, gave the following description of the school:

The programme of tuition at Eden Grove seems by far the most exhaustive, the most complete, and the cheapest anywhere to be found in the metropolis of London, and this not exactly so much owing to the number of subjects included, but rather on account of the teaching staff, from its chief downwards. The writer well remembers the erudite and devoted principal when he wore the robes of a clergyman of the Scottish Episcopal Church. The Very Reverend E.B. Fortescue, M.A., late Provost of Perth, sacrificed all in the Anglican Church for conscience sake and became a Catholic laymen [sic]. He lives next to the School-house and is in daily attendance at the establishment. It would be an impertinence to intrude on this cultured gentleman's privacy to dilate upon his attainments and his extraordinary aptitude for such work as he has now undertaken. His association with Perth, and, prior to that, his distinguished Oxford career, speak far more eloquently than any printed words.

('page 26')

Edward's death came somewhat unexpectedly on August 18, 1877. His son Edward Francis caused to be printed fifty copies of a forty-four page pamphlet "In Memory of the Very Rev. Edward Bowles Knottesford Fortescue." It comprises a copy of a letter to the son Lawrence in Canada and a collection of newspaper obituaries. It recounts how Edward had been sick that winter previous and took the occasion to make out his will. But with the summer he seemed to have recovered completely and on August 4th, went to The Dominican Priory at Haverstock Hill for a luncheon. The next day at the High Mass he felt ill and left the church before the service was over. He never left his bed after that day.

During the two-week illness his son, Edward Francis, was a daily visitor and the rest of the family who were within visiting distance came also. On the last day of his life Father Tondini, a Barnabite priest who had recently formed a Roman Catholic Society to pray for the restoration of visible unity among Christians, paid a rather long visit. When he left Edward told his son they had been talking about Christian unity, the object "nearest and dearest of my heart, and for which I have prayed more than anything else during the whole of my life."

Edward's funeral was superintended by his son, who followed as far as possible "the course he himself had taken at my Grandfather's death." The library of his home was hung in black and there he lay in state, "watched by his sons and daughters, wife and friends" for three days. The evening of the last day of the wake

('page 27')

the body was removed to the church, accompanied by a choir. Solemn Vespers for the Dead were chanted and an honour guard of friends watched the night. In the morning Matins for the Dead were sung, followed by High Mass and the Absolution service. The body was then carried in an open hearse to the Roman Catholic cemetery of St Mary's at Kensal Green. There were four pall bearers, two Anglican and two Roman clergymen.

Great numbers of people passed through the house to view the remains and the funeral was attended by many persons of eminence, both of the Church of England and of the Church of Rome - all the obituaries make this observation, but nowhere are names mentioned. Both the Archbishop of Canterbury, Edward's brother-in-law Archibald Tait, and the Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster, Edward's one time mentor Edward [sic] Manning, had reason to attend.

At his death Edward left the children of his first marriage, Edward Francis, his heir, Maria who married Augustus Macirone, Lawrence, George and Vincent, as well as a young widow and three small children from his second marriage. The children were Clare aged 5, Adrian, aged 3, and Raphaela 10 months.

('page 28')

ADRIAN'S MOTHER

Gertrude Martha Robins was the daughter of the Rev. Sanderson Robins who buried his first wife in April, 1834 and married his second in the same month a year later. The second wife was the daughter of Joseph Foster Barham, M.P. whose wife was the youngest daughter of the eighth Earl of Thanet, a family that provided The Complete Peerage with some interesting examples of English society. The eighth Earl kept the well-known courtesan Nelly O'Brien whose portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds is in the Wallace Collection. The ninth Earl was convicted for riot. The eleventh Earl left his estate to a French gentleman.

Sanderson Robins was a popular preacher in his day as well as the author of an impressive list of books on topics of current religious interest, two of which reached a fairly wide audience: The Church Schoolmaster (1850) and The Whole Evidence Against the Claims of the Roman Church (1855). He died suddenly in 1862, leaving a widow and four children, a son by his first marriage, and Katherine Gertrude, Gertrude Martha and Francis William by his second.

Both girls were attracted to Anglican nunneries, Katherine to Clewer, the foundation point of the Community of St John the Baptist, one of the most flourishing and successful of Anglican communities for women.

Gertrude was less fortunate in her choice of a religious community. Somehow she fell in with Joseph Leychester Lyne, known as "Father Ignatius." His story

('page 29')

is long and complex. He was a deacon of the Established church, the would-be father of a Benedictine revival in that church, the superior of a monastery in Wales, and a sometime dupe of the disreputable Mar Timotheos [Joseph Rene Vilatte, an irregularly ordained priest and bishop]. Early in his career Lyne formed a group of women into a sisterhood as a second order to his revived Benedictines. When the Bishop of Norwich would have no more of him he moved to London and established a mission house on Hunter Street of which "sister" Gertrude Robins became the prioress. Sister Gertrude's priorship seems to have depended on the fact that her private money was the mainstay of the house on Hunter Street. When she had a falling out with Ignatius he determined to put her out of the Order which was equivalent to putting her out of her own house. He wrote her a letter telling her she was "solemnly excommunicated from our Holy Congregation." Gertrude showed the letter to her mother who passed it on to her friend, Edward Fortescue's sister-in-law, the wife of Bishop Tait. Lyne was inhibited, i.e. prevented from, functioning in the Diocese of London. By the end of 1868 the matter between Gertrude and Ignatius was at an end. She then went of [sic] join the Community of St Mary and St John in Scotland. This community, founded as a small orphanage in Leith was moved to Perth with the assistance of Edward Fortescue, who became first Warden of the Society. There can be little question that this community was the medium of the courtship of Gertrude and Edward.

('page 30')

The thirty-eight year old widow and her three small children moved from Rose Villa in Holloway to a home at 48 Maitland Park, Haverstock Hill and later to 85 Boulevard Marriette, Boulogne-sur-Mer, France, where she died December 3, 1886, aged 47. Edward's will provided for Gertrude and the children, and in 1878 her mother inherited the estates of the last Earl of Thanet. But financial security was no substitute for emotional satisfaction. Gertrude was unwell these final years of her life. Her daughter Clare remembered her as often lying in a darkened room with severe headaches. The executors of Gertrude's will were Edward Francis Fortescue and George Fortescue of the British Museum. Edward Francis having died in 1886, aged 46, the full burden of affairs fell to George. It was a task he would perform for family members until his own death in 1912. One result of this settlement was the sale of the library at Alveston Manor House, referred to as Edward's but mostly the collection of his father Francis. The auction took place on the 16th and 17th of March, 1887, in the rooms of Sotheby, Wilkinson and Hodge in the Strand, London. The gross proceeds of the sale were £468.13.6. The printed copy of the contents of the sale is preserved in the British Library and shows in its titles the ecclesiastical interests of both Francis Knottesford and his son Edward.

The upbringing of the children fell to Gertrude's sister Katherine. It is not recorded when she left the sisterhood at Clewer. She became a Roman Catholic in 1870. She was now living with her aging mother at 6, Darlaston

('page 31')

Road, Wimbledon, across the street from the Jesuit church there.

The new burden that fell on the maiden aunt and seventy-four-year old grandmother was somewhat alleviated by the English custom of sending children of this class in society away to boarding school. Fifteen-year old Clara and twelve-year old Raphaela were sent to the Sisters of the Sacred Heart at nearby Roehampton, thirteen-year old Adrian stayed at home while attending St Charles' College at Bayswater. In 1891 he entered Scot's College in Rome to begin his preparation for ordination as a Roman Catholic priest.

The grandmother died in December, 1899. In 1901 the Wimbledon house was sold and Katherine Robins went to live in Florence, Italy, where she died in 1907. Clara Fortescue married George Frederick Squire in St Patrick Church, Soho, June 7, 1902, the Bishop of Nottingham (Robert Brindle) performing the ceremony. She died in 1954 at the age of 82 leaving children and grandchildren. Gertrude Raphaela went to Russia as a governess until the Revolution drove her to the south of France. She only returned to England toward the end of her life. She died in 1966 at the age of 90.

With thanks to Stanley Lapidge for researching and supplying this account - 2018

...................................

Father Adrian Fortescue son of Edward Hawks Knottesford Fortescue was a direct descendant of the Blessed Adrian Fortescue (d. 1539),

On 20 December 1922, Adrian Fortescue was diagnosed with cancer. He preached his last sermon on 31 December, a simple but profound lesson on the reality of the Incarnation of Christ, ending with the words, "That is all I have to say." On 3 January 1923 he left Letchworth for Dollis Hill Hospital, where he died of cancer on 11 February. Against the wishes of his family, he was buried at Letchworth, among his own parishioners.

Find A Grave Memorial.

Research Notes: Research Notes:

Image Courtesy: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adrian_Fortescue

Other Records Other Records

1. Census: England, 3 Apr 1881, Hampstead LND MDX. Adrian is recorded as a son aged 7 born LON

2. Census: England, 31 Mar 1901, Walthamstow Essex. Adrian is recorded as head of house unmarried aged 26 a Roman Catholic Priest a worker born in London

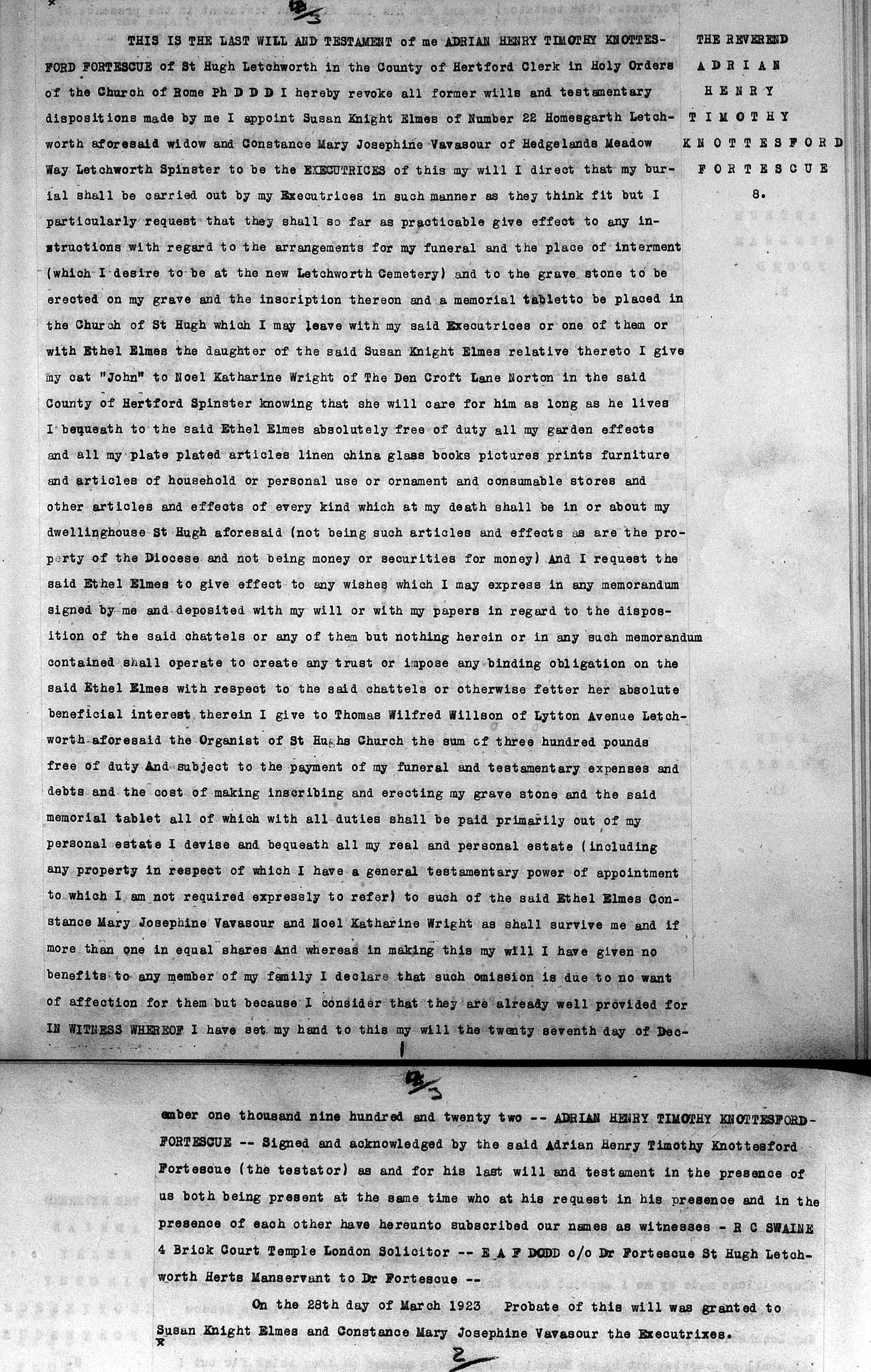

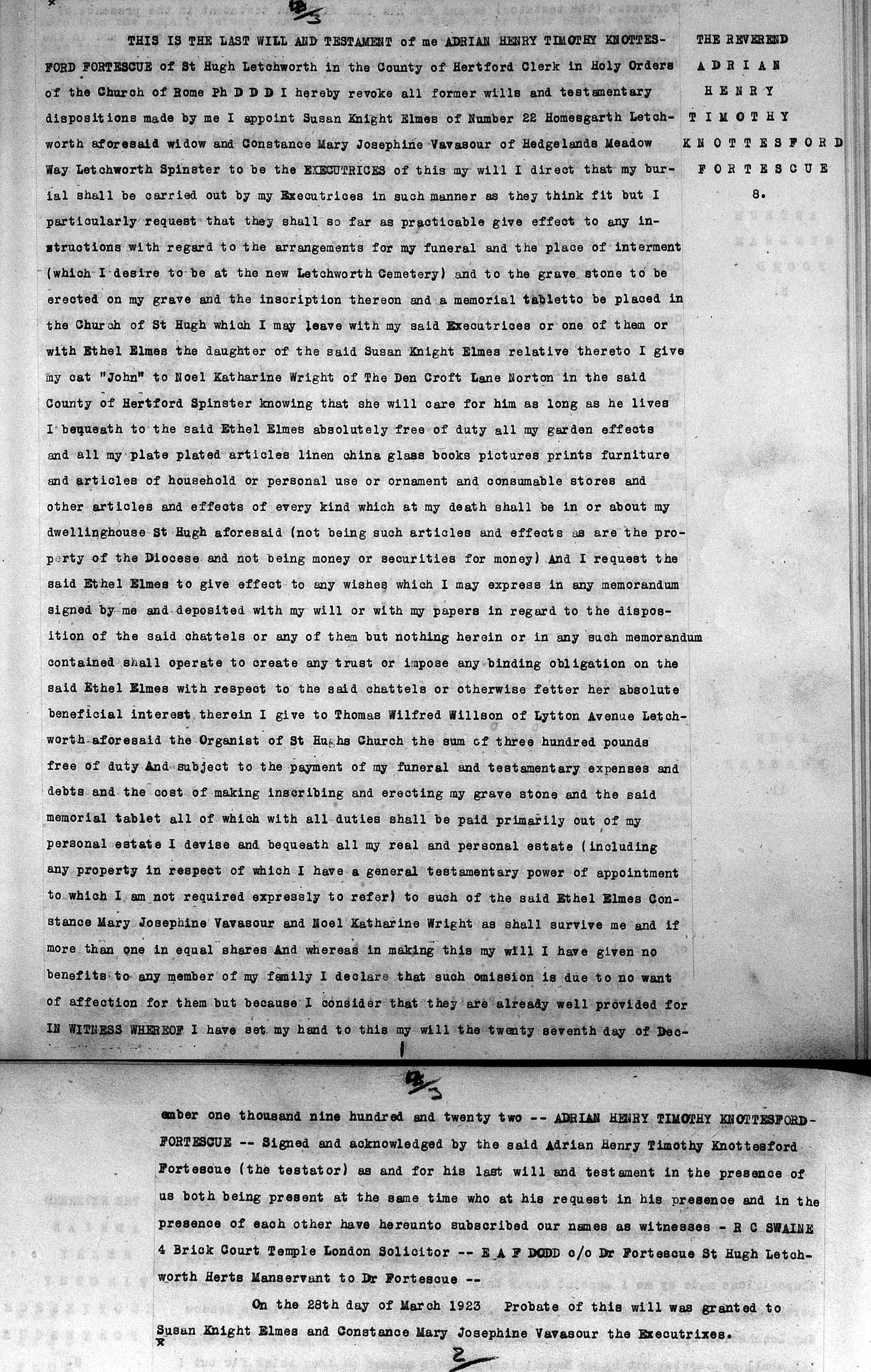

3. Adrian Henry Timothy Knottesford Fortescue: Will, 27 Dec 1922.

THIS IS THE LAST WILL AND TESTAMENT of me ADRIAN HENRY TIMOTHY KNOTTESFORD FORTESCUE of St Hugh Letchworth in the County of Hertford Clerk in Holy Orders of the Church of

Rome Ph D D D

I hereby revoke all former wills and testamentary dispositions made by me I appoint Susan Knight Elmes of Number 22 Homesgarth Letchworth aforesaid widow and Constance Mary Josephine Vavasour of Hedgelands Meadow Way Letchworth Spinster to be the EXECUTRICES of this my will

I direct that my burial shall be carried out by my Executrices in such manner as they think fit but I particularly request that they shall so far as practicable give effect to any instructions with regard to the arrangements for my funeral and the place of interment (which I desire to be at the new Letchworth Cemetery) and to the grave stone to be erected on my grave and the inscription thereon and a memorial tablet to be placed in the Church of St Hugh which I may leave with my said Executrices or one of them or with Ethel Elmes the daughter of the said Susan Knight Elmes relative thereto I give my cat "John" to Noel Katharine Wright of The Den Croft Lane Norton in the said County of Hertford Spinster knowing that she will care for him as long as he lives

I bequeath to the said Ethel Elmes absolutely free of duty all my garden effects and all my plate plated articles linen china glass books pictures prints furniture and articles of household or personal use or ornament and consumable stores and other articles and effects of every kind which at my death shall be in or about my dwellinghouse St Hugh aforesaid (not being such articles and effects as are the property of the Diocese and not being money or securities for money) And I request the said Ethel Elmes to give effect to any wishes which I may express in any memorandum signed by me and deposited with my will or with my papers in regard to the disposition of the said chattels or any of them but nothing herein or in any such memorandum contained shall operate to create any trust or impose any binding obligation on the said Ethel Eames with respect to the said chattels or otherwise fetter her absolute beneficial interest therein I give to Thomas Wilfred Willson of Lytton Avenue Letchworth aforesaid the Organist of St Hughs Church the sum of three hundred pounds free of duty And subject to the payment of my funeral and testamentary expenses and debts and the cost of making inscribing and erecting my grave stone and the said memorial tablet all of which with all duties shall be paid primarily out of my personal estate I devise and bequeath all my real and personal estate (including any property in respect of which I have a general testamentary power of appointment to which I am not required expressly to refer) to such of the said Ethel Elmes Constance Mary Josephine Vavasour and Noel Katharine Wright as shall survive me and if more than one in equal shares And whereas in making this my will I have given no benefits to any member of my family I declare that such omission is due to no want of affection for them but because I consider that they are already well provided for IN WITNESS WHEREOF I have set my hand to this my will the twenty seventh day of December one thousand nine hundred and twenty two

ADRIAN HENRY TIMOTHY KNOTTESPORD-FORTESGUE

Signed and acknowledged by the said Adrian Henry Timothy Knottesford Fortescue (the testator) as and for his last will and testament in the presence of as both being present at the same time who at his request in his presence and in the presence of each other have hereunto subscribed our names as witnesses

R C SWAINS 4 Brick Court Temple London Solicitor

E A F DODD c/o Dr Fortescue St Hugh Letchworth Herts, Manservant to Dr Fortesoue

On the 28th day of March 1923 Probate of this will was granted, to Susan Knight Elmes and Constance Mary Josephine Vavasour the Executrixes.

Fortescue the Rev Adrian Henry Timothy Knottesford of St Hugh Letchworth Hertfordshire clerk died 11 February 1923 at St Andrews Hospital Dollis Hill Willesden Middlesex Probate London 28 March 1923 to Susan Knight Elmes widow and Constance Mary Josephine Vavasour spinster. Effects £4127 18s 1d

National Probate Calendar.

|

Cause of his death was cancer.

Cause of his death was cancer.