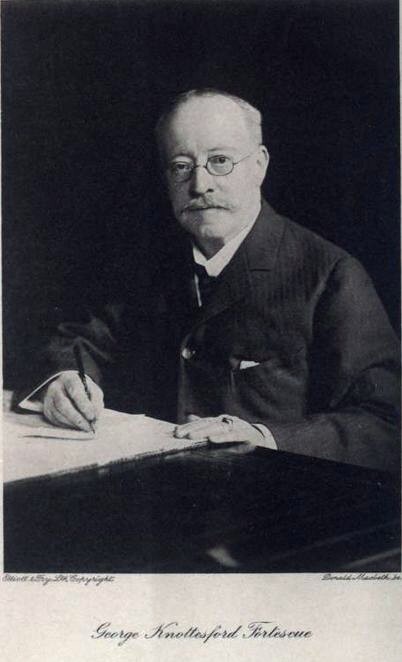

George Knottesford FORTESCUE [14690]

- Born: Oct 1847, Alveston WAR

- Marriage (1): Ida BLATCH [14691] on 22 Apr 1875

- Marriage (2): Beatrice ST LEON [14692] on 9 Oct 1899 in Reading Berkshire

- Died: 26 Oct 1912, London aged 65

- Buried: St Pancras Cemetery Finchley MDX

General Notes: General Notes:

Foundation Scholars of Chartherhouse 1614-1872

Alumni Carthusiani. Pg 262.

George [Knottesford] Fortescue. 16 Jul 1860, born 30 Oct 1847, left 7 May 1862, in place of Thomas Bowes Howard Lord Panmure.

Fourth son of Very Rev Edward Bowles Knottesford Fortescue, Dean of Perth; assistant in the British Museum Library 1870, Superintendent of the Reaqding Room 1884, Assistant Keeper 1890, and Keeper of the Printed Books 1899; LLD (Aberdeen); President of the Library Assn 1901, and of the Biographical Society 1909; Author of "Subject Index of Modern Works in the British Museum 1881-1900", with supplements to the year 1910; "Napoleon and the Consulate" 1908; died 26 Oct and buried in St Pancras Cemetery, Finchley, 31 Oct 1912; He married (1) Ida daughter of the Rev William Blatch, Incumbant of St John's Perth; (2) at St Mary Reading, 9 Oct 1899, Beatrice, widow of H.W. Jones M.I.

THE LIBRARY.

Third Series,

No. 13, VOL. IV. JANUARY, 1913.

GEORGE KNOTTESFORD FORTESCUE. - A MEMORY.

RICHARD LE FORT was cup-bearer to Duke William of Normandy, and accompanied his lord on the expedition to England. He fought at Senlac, and during that battle saved the life of the Conqueror by interposing a mighty shield between him and a Saxon weapon. Henceforth he was known as Richard of the Strong Shield, ' le Fort-Escu,' and long afterwards, when mottoes came into fashion, his descendants, in commemora- tion of this incident, took for their devise the Latin sentence, ' Forte Scutum Salus Ducum.' Richard, whose name occurs in the Roll of Battle Abbey, returned to Normandy, where descendants of him still exist ; but his eldest son Adam, who had also fought at Senlac, remained in England and acquired lands at Wymondestone, Winestane or Wimpstone, in the parish of Modbury on the Erme, in that part of Devon known as the South Hams. This much is only family tradition. At the time of the Domesday Survey, Winestane formed part of the great estates of Robert Earl of Mortain, as tenant in capite^ and one Rainaldus held it under him. But the manor of Mortberie, which was the nearest the Norman scribes could get to Modbury, was held under the same Earl by Ricardus, who may just possibly have been Richard le Fort. The Domesday man was at any rate probably a Norman, for a Saxon, Wado, had held it ' temporc Regis Edwardi.' The earliest Fortescue document is a deed in the Library of Eton College, of the end of the twelfth century, whereby Ricardus Fort Escu confirms to the Priory of Modbury (a cell of St. Pierre sur Dives in Normandy) the lands which his grandfather Radulfus, and his father Ricardus, had given to it.

There are other documents about the Richard who executed this charter, who was a Knight of St. John, and was certainly living in 1199, but no others about his father Richard or his grandfather Ralph, the latter of whom we may conjefture, judging by the length of generations, to have been the son of Adam, son of Richard le Fort. The lands in question, of which the bound- aries are given, appear to be in the manor of Modbury, not in that of Wimpstone. There is a grant (or possibly a confirmation) of 1209 by King John giving Wimondeston to Sir John Fortescue, a brother of the Richard of 1199; so that family tradition may be right about the parish, but wrong about the actual manor held by the shadowy Richard and Adam of the Conquest.

Ninth in descent from this Sir John was another John who was living in 1461. His third son, also John, acquired the estate of Spridlestone, in Brixton, near Plympton. He had a son Richard, who succeeded him at Spridlestone, and a second son Nicholas, who was Groom Porter, whatever that may be, to King Henry VIII, and died in 1549. To him in 1542 were granted the lands of the Nunnery of Cookhill, in Worcestershire, near Alcester. Seventh in descent from the Groom Porter was the Reverend Francis Fortescue, who inherited from his father's cousin, John Knottes- ford, the estate of Bridgetown, with the manors of Alveston and Teddington, in Warwickshire, and assumed the additional surname of ' Knottesford,' quartering with the ' azure, a bend engrailed argent, cottised or ' of the Fortescues, the c argent, a cross engrailed gules ' of the Knottesfords, which make between them an unusually pleasing coat.

On the death without male issue of John and Henry, sons of John Fortescue of Cookhill, Francis Fortescue-Knottesford became the head of the Cookhill branch, and, since the male lines of Wimpstone, Pruteston, and Spridlestone had all become extinft in the seventeenth century, the head of the whole house of Fortescue. He did not, however, inherit Cookhill, which had been sold by his first cousin, John, early in the nine- teenth century. The son and heir of Francis was the Very Rev. Edward Bowles Knottesford Fortescue (he changed the order of names), Provost of the (Scottish Episcopalian) Cathedral of St. Ninian at Perth. He married as his first wife Frances Anne, daughter of Archdeacon Spooner, by whom he had six sons, the fourth of whom was George Knottesford Fortescue, who, it will be seen, was, therefore, twenty-fifth in descent from the cup-bearer of the Conqueror.

The family history of the Fortescues of Cookhill is not especially distinctive except in one point, which they probably share with a good many other families, though in their case it is recorded more clearly than usual. Nicholas the Groom Porter no doubt followed Henry VIII in his separation from Rome, as did most other people. There is nothing to show that he agreed with his kinsman, Sir Adrian Fortescue of Salden, in his resistance to the King's schismatical policy, and he took his share of monastic property. Dying in 1549 he had no opportunity of expressing an opinion one way or another on the greater changes made by the government of Edward VI. His son William, whatever may have been his line of conduct during that short reign, was probably reconciled to Catholicism with the rest of the country under Mary, and was one of the many Worcestershire squires who did not conform to Protestantism under Elizabeth. He died in 1605. His son, Sir Nicholas, was suspected at the time of the Gun-powder Plot, but evidently was not implicated in it, for nothing came of the suspicion. He remained a Catholic, as did the descendants of his brother and eventual successor, John, for several generations.

The position of Catholics during the early seventeenth century had considerable elements of danger in it ; but when after a while the penal laws were not actively enforced, it ceased to be a danger and became only a nuisance, especially to a Catholic landed gentleman with a large family of sons. All the professions fit for a gentleman were barred against them by the Test Act of 1673, and so were the public schools and universities ; and nothing was left for those who had no vocation for the priesthood but either to descend to commerce or to the lower walks of the medical profession it will be remembered that Dr. Slop was a Catholic, and Sterne probably knew very well what he was doing when he represented him as one or else to loaf about at home and sink into illiterate roystering sportsmen like Scott's Osbaldistones, who, it is said, were actually drawn from life, Thus it was that many not especially devout Catholics, whose honour as gentlemen would not allow them to desert their religion while there was real danger in it, fell away before the pin-prick policy of the Test Act. It happened that for some time the problem of what to do with younger sons did not press upon the Fortescues of Cookhill, for the simple reason that there were no younger sons. At last, at a time when the penal laws had fallen into disuse, and when meddling common informers who tried to get them enforced were severely snubbed by the judges, there arose a Fortescue of Cookhill who had five sons. The circumstances were too much for him, and he conformed to the Church of England, brought his sons up in that religion, and so was able to provide them with professions. One of them, John, the eldest, entered the navy in 1739, and was in Lord Anson's ship the ' Centurion ' in the voyage round the world in 1740. Another became a clergyman, and the others went into various professions. Curiously enough, his grandson, the Rev. Francis Fortescue-Knottesford, who died in 1859, though his opinions were fully matured long before the Traftarian movement, had very strong Catholic tendencies. It is said of him that he used to recite the Breviary Offices daily whether Sarum or Roman is not recorded. It might have been either, for he was a great collector of liturgical books at a time when few cared for such things. And his son, the Provost of St. Ninian's Cathedral, returned to the faith of his ancestors in later life.

Though the family of Fortescue can hardly be said to come into what may be called first class history, its members have done their fair share and more in the building up of England. As fine fighting men, loyal to their King by land or sea, as peers, judges, statesmen, clergymen, and officials, they have made their mark in the world, and, perhaps the proudest distinction of all, the House of Fortescue has produced one beatified martyr. There have not been many literary men or high- class scholars among them, for they have been men of affairs rather than students, and such part as they have taken in literature and scholarship has been usually incidental rather than essential. Curiously enough, too, the family has not as yet produced a single bishop.

The Grand Old Gardener and his wife may or may not smile at the claims of long descent but many will still agree with Colonel Newcome that every man would like to come of an ancient and honourable race. It was essential to the personality of George Fortescue that he did come of a very ancient and very honourable race, and though, like Jaques about another matter, he gave Heaven thanks and made no boast of it he was by no means unconscious of it. This must be my apology for the introduction of so much family history into the biography of an eminent librarian.

George Knottesford Fortescue was born at Alveston Manor, in October, 1847. It is characteristic of that remarkable man, his father, that the actual day of his birth is not recorded, though that of his baptism is. In 1847, though the Registration Act had been in force for eleven years, it had not yet become compulsory to notify births to registrars. The registrar was directed to 'inform himself of the occurrence of a birth in his district, and the public, though obliged to give information if asked for it, were not compelled to give it unasked. Probably in this case the registrar did not inform himself. The average man would usually appreciate the benefits of registration, and voluntarily give information ; but the elder Fortescue was far too Conservative to like such an innovation, which probably seemed to him to tend to exalt the mere natural birth above the spiritual re-birth of baptism. This idea was not uncommon with early members of the Church party of which Provost Fortescue became a very distinguished member.

Alveston Manor is situated about two miles out of Stratford-on-Avon, in the heart of the Shakespeare country. Wilmcote or Wincot, where Marian Racket was the fat ale-wife to whom Christopher Sly owed fourteen pence for sheer ale, is on Fortescue property ; the church there was built by the Provost of St. Ninian's, and the living is now in his grandson's gift. The manor house is a fine old timbered building. At the time of George Fortescue's birth, his grandfather was still living there. His father was then incumbent of Wilmcote, but became Provost of St. Ninian's Cathedral at Perth in 1850, so that his son's early recollections were associated with Scotland rather than Warwickshire. His father was a very remarkable man, of fine presence, with a striking face, and delightfully courteous manners of somewhat old-fashioned type. When at Oxford he had come under the influence of the Tracts for the Times, which had then not long begun, and these ideas, sown upon ground already prepared by Catholic family tradition, only three generations off, bore plentiful fruit, and made him a very advanced High Churchman. Like most of the advanced churchmen of the period, he was an extreme Tory in his political views, for Radical ritualists were then unknown. The rather violent anti-Roman views of a large school of modern High Churchmen were then also quite unknown. The idea of that period was that although, as Neale put it, England's Church is Catholic, though England's self is not, and individual secession was to be deprecated, the Church of Rome was to be largely admired and imitated, and corporate reunion to be hoped and striven for. But the ideal was Gallicanism rather than Ultramontanism, and the triumph of the latter in the Vatican Council changed the tone of the Anglican High Churchmen completely.

Provost Fortescue was a masterful man, very firmly convinced that his opinions were the only right ones, and his family were all expected to think and praftise what he preached. I fear that all his sons except the eldest, who remained a convinced Anglo-Catholic to the day of his death, were rather a disappointment to him in that respeft; but there was another influence which very greatly affected, at any rate his son George, if not others of them. Provost Fortescue had married Frances Anne, daughter of Archdeacon Spooner, of a well-known Warwickshire family. By her he had seven children : (i) Edward, who was in the army, succeeded his father at Alveston, and died about twenty years ago, leaving two sons, the eldest of whom, the Rev. John Nicholas Knottesford- Fortescue, is now the head of the family, and two daughters; (2) John, who died unmarried in the early seventies of last century; (3) Lawrence, now Assistant-Comptroller of the Canadian Mounted Police ; (4) George ; (5) Vincent, now Canon of St. Michael's, Coventry, and Reftor of Corley, Warwickshire; (6) Charles Ninian, who died as a child; and (7) Mary, who married George Augustus Macirone, of the Admiralty. A sister of Mrs. Fortescue, Catharine Spooner, married Archibald Campbell Tait, then head-master of Rugby, but afterwards successively Dean of Carlisle, Bishop of London and Archbishop of Canterbury. The influence of this great man, who was almost like another father to his wife's nephews, who were all exceedingly fond of him, never left George Fortescue to the end of his life. As a boy he was very unresponsive to his father's religious teaching, and, whatever his brothers may have done, neither took nor would appear to take, even for the sake of peace, the slightest interest in any of it. He had a story of how he was turned back from Confirmation in disgrace, having been caught reading a very inappropriate novel in bed on the morning when he should have received that Sacrament, which evidently interested him but little. This and other incidents of the same sort, provoked by a well meant but apparently very injudicious treatment, caused strained relations between the boy and his father, who treated him with a good deal of sternness and severity, and seemed to look upon him as the black sheep of the family. Happily, during the last few years of his father's life they were on the most cordial of terms, and thoroughly appreciated each other. Thus it was that George's home life at his father's house was not particularly happy, and the pleasantest memories of his boyhood were of the days spent at London House or Fulham Palace with the Taits, of both of whom he was very fond and whose influence on him was strongly for good. His mother died in 1868, when he was one-and-twenty years of age. I have an indistinct memory of her coming two or three times to see her sons at school, a fair-haired lady with a gentle face, and a very devout manner in church. I think she was an invalid for some time before her death, and her health prevented her from living at Perth.

I knew his father very well during his later years. He died in 1877. He had married as his second wife in 1870 Gertrude, daughter of the Rev. Saunderson Robins, vicar of St. Peter's in Thanet, an old acquaintance of my own parents. After their marriage they both became Catholics and went to live close to the Church of the Sacred Heart in Eden Grove, Holloway, in a picturesque old house with a large garden, where I often visited them. He had, of course, to behave as a layman, but he always dressed in black, and I think he had considerable doubts about the invalidity of his Anglican Orders he did not live to see the decision of Leo XIII on the subjeft. He was full of humour and used to have his letters addressed Mr. Fortescue, and refused to assume Esq., as many clerical converts have done. I remember that when his son George was married, the bridegroom and his ' best man,' myself, consulted about the filling up of the register, and, wishing to do what he would like, though we were both Anglicans, we decided that it would be best to describe him as gentleman. To this, when he saw it, he objected strongly, saying that "Clerk in Holy Orders " was his proper designation by which, I think, he meant more than that it was still his legal title. He used to read the Epistle at Mass, which, of course, can be done by a layman, and was part of the duty of a parish clerk in Pre-Reformation and for a time in Post-Reformation England, though it is very unusual now, so much so that I never met with any other instance.

He was a most agreeable and interesting man, and of varied information, especially on ecclesiastical subjects, and an excellent talker. As an Anglican he had been a fine preacher, and was a considerable leader of the extreme Catholic school, and especially of those who desired re-union. He was the first President (I am not sure of the exact title) of the Association for Promoting the Unity of Christendom, which was founded, I think, in about 1859, and of which his son-in-law, George Macirone, was later for many years secretary. By his second marriage he had three children, one of whom, the Rev. Adrian Knottesford Fortescue, D.D., is a distinguished Catholic writer, chiefly on subjects connected with the Eastern Churches.

Provost Fortescue's Anglican position was the cause that he sent two of his sons, George and Vincent, to St. Mary's College, Harlow, which had been started in the fifties as a school for sons of the extremer members of the Catholic party in the Church of England. It was encouraged by the leaders of that section, and for a while appeared to flourish, so that in 1861 a new building on a fairly large scale was needed, and the foundation- stone was laid, amid great pomp and hopefulness, by the Hon. Colin Lindsay, the first President of the English Church Union, who backed his opinion by sending one of his own sons there. Eucharistic vestments were worn, incense was used, fast-days were kept, confession was practised, and I have never been able to find any essential difference between the theology taught there and that which has the sanction of the Holy See, except, of course, as regards the position of the Church of England. And there was plenty of church-going and theology. Matins and Evensong were sung daily. There were Celebrations of the Holy Communion we used to call it "Mass" on Sundays and Thursdays, at which the whole school were present. Early Confirmation and frequent Communion were encouraged. We had a whole holiday on all red-letter Saints' Days. On the other hand, during Holy Week ordinary work was suspended, and everything was theology and services, and on Good Friday absolute silence was observed for the whole day, and it was made a "black fast" Were were overdosed with religion ? I do not know. Boys are generally rather bored by it, and probably few of us enjoyed fast-days and Holy Week, though we liked Saints' Days ; but judging from those whom I have met in later life and they are a large proportion of the whole I think that the religion was presented in a manner which has caused very few, however they may have drifted away from the form of it, to look back upon it with repugnance or dislike ; and even those who are not religious now look back with a certain kindly feeling to the beautiful ideals, never, alas, to be realised, of the extremists of that day, a feeling which the sad debacle of our old school could not do away with. The founder, the Rev. Charles Jonathan Goulden, a man of Jewish extraclion, was a very mixed character; the discipline was fitful and irregular, the scholarship inaccurate, and everything more or less ramshackle in its ways. Of the two hundred boys or so who passed through the school during the twelve years of its effective existence, only three that I know of, George Fortescue, Father William Black, and W. H. Mallock, have ever even attained to the honours of "Who's Who" ? Looking back, it does not seem surprising that the school ceased to exist in 1867.

I first met with George Fortescue in December, 1860. His brother Vincent came to Harlow in that year, and shortly before the Christmas holidays George came there as a visitor, so as to accompany his younger brother to Perth when the holidays began. He was then thirteen (nearly a year older than I was), short for his age, with an immense mop of very thick, crisp, and tightly curled hair, parted in the middle and spreading out on either side. It suggested the obvious nickname of "Poodle" His hair was almost woolly, and though it was very light in colour, he used to say, long after those days, that he would never have ventured to go to the West Indies, as his brother John had done, for there he would inevitably have been suspected of colour. Yet there was not an atom of any but European blood in him. He was very merry, though not noisy, and exceedingly active, high-spirited, and impulsive. Under the circumstances of his visit, which was really to his brother, he became for the time a sort of honorary member of the school, and was at once a general favourite. He made two or three more visits during 1861, and at the beginning of 1862 came as a pupil. He was very good at games, and I remember that at his first visit he displayed great skill at a winter amusement, known in those days, and perhaps still, as snob cricket. This was a form of single wicket, with rather go-as-you-please rules to it, played in a gravelled playground with a stick, generally a worn-out cricket stump, and an india- rubber ball, usually a solid one, at a wicket chalked on a brick-built gate-post. And to the reason for his expertness hangs a tale. He and some of his brothers and his cousin Craufurd Tait used to play it on wet days in the library at Fulham Palace, using as a wicket some large folio set up on end. On one occasion Bishop Tait came in and found Fuller's "Worthies" being used in this way, and mildly suggested that some less venerable work might be substituted, so that thenceforth, under episcopal sanction, Morhoffii Polyhistor became their wicket. Long years after, in about 1906 or 1907, George Fortescue went to lunch at Fulham Palace with the present Bishop of London, this being the first time he had been to the house since Tait left it in 1868. Of course he was shown the library, and he somewhat surprised the Bishop by asking for "Morhoffii Polyhistor" of all improbable books. He found it for himself in its old place, still bearing the marks of the balls, but not very seriously the worse for them.

I think my friendship with Fortescue dates from his first visit to Harlow. We took to each other from the first, and we remained friends without a break for fifty-two years, though there was a short gap from 1865 to 1869, when we never saw each other. As a boy and as a man he was of a very warm-hearted and affectionate nature, unselfish to an unusual degree, never seeking his own advantage in anything, even when he might have done so without blame. At school, as in the world, he never made an enemy in all his life, even of those whom personally he disliked for he had very strong dislikes as well as likes and he made many friends. I do not think that his character ever really changed, but at school this unselfishness manifested itself in strange ways. I never knew him do anything to the detriment of anyone else ; but for the effect of his actions on himself he appeared to be perfectly reckless. He could not be called a studious boy in any sense, though he read what pleased him, and had for his age a good taste in literature, both of prose and verse, and he thought out and talked out, in schoolboy fashion, of course, many things which did not appeal to the ordinary ' human boy.' Indeed, I should say that he was rather romantic in his ideas, and held decided views on many subjects on which school boys do not often make up their minds. And he expressed them freely, as he did throughout his life. Though he had many harmless affectations, he was saved from any taint of priggishness by a certain diffident humility and consciousness of his own limitations, which, I think, was a part of his unselfishness. Had he chosen he might have excelled in school-work as well as in games; but, much to his regret in after life, even the simple, and not wholly painless, arguments of the period could not induce him to prepare a lesson. He would come up to class with some uncertainty as to where it began. As for rules, they were made to be broken, whenever they interfered with his inclinations, and often when they did not, out of sheer defiance. I remember once that another boy, no particular friend of his, dared him to join him in running away. The other boy may have had reasons for attempting this scholastic suicide. He was not popular, and when school boys are unpopular their companions are apt to let them know it. But Fortescue had no reasons. He was extremely popular, and the school, with all its educational faults, was anything but a Dotheboys Hall, so that he was quite happy there. Also he was fully aware of the consequences. But he was ' dared ' to do it, and as a Fortescue and a gentleman what could he do but go ? They went up to London, and after some harmless adventures, which appeared to them rather dissipated, came to the end of their money and turned up, not at all repentant, but somewhat the worse for wear the other boy at his mother's house, and Fortescue at the Bishop of London's. The other boy did not return to school, and it was better so. Fortescue was brought back by George Macirone, who was afterwards his brother-in-law.

While this incident did not end Fortescue's school career, the end came in rather a stormy manner. At Harlow from time immemorial there had been held a large and important fair on the Feast-day, Old Style, of St. Hugh, Bishop of Lincoln, in whose honour and that of Our Lady St. Mary the parish church is dedicated. As St. Hugh's Day New Style is 17th November, this was naturally on 29th November; but as in 1863 that was a Sunday, the fair was held on the Saturday, and inaugurated, as usual, by a kind of "First Vespers" on the Friday. It was a rowdy business, and we were not allowed to go to it after dark. Having, nevertheless, attended this ceremonial the night before, and not liked it sufficiently to repeat the visit, on the evening of that Saturday it occurred to George Fortescue and two others that tobacco was attracting them, and that the unfinished new wing of the college was a sufficiently secluded place in which to smoke it, being out of bounds. Before lighting up had begun, however, voices of certain "prefects" were heard, and one he died three or four years ago, a retired colonel was heard to conjecture that they had gone there to smoke. The three lay low in a distant quarter, not very easy of access with no stairs, and the voices died away. After a sufficient smoke they returned to the school, and found to their horror that a special "call-over" had been instituted, in view of the fair, that they had been reported missing, had been searched for, and had not been found anywhere on the premises, even in the forbidden new building. There was no other conclusion than that, like Robin Hood and Little John in the Helston Furry Song, they all had gone to the Fair O ! They were called up and questioned. They told the plain and unvarnished truth, omitting, of course, the wholly irrelevant and superfluous nicotian detail, and, sad to relate, they were not believed. Nothing, however, could turn them from their story even when they were examined separately and in the end, though the impositions were rather disproportionate to the very slight offence of going into the new building, they were supposed to be for that only. In Fortescue's case, however, the affair was complicated with an adventure with a certain tramp, who had represented himself as coming from the neighbourhood of Stratford-on-Avon, and professed to know all about the Fortescue family. To him George had given some food and an old coat, and probably any loose cash that he had about him. When the Headmaster represented to him that the food was not his to give away an aspect of the case which had, very naturally, not occurred to the boy's mind he put his hand into his pocket, pulled out a handful of coppers, and said in a rather contemptuous tone, which through all his life he could assume when he chose, I am quite willing to pay for it. This naturally did not mend matters, and the result of the term's misdemeanours was an exceedingly unsatisfactory report, which caused his father to remove him from the school.

In the early sixties, as previously, the merchant shipping service was largely recruited from boys whose parents did not know what else to do with them. George Fortescue had never shown the slightest inclination for the sea, but in accordance with this tradition he was apprenticed on board a certain ship commanded by a connection by marriage of his family. He was to live in the cabin, and, I suppose, was to be taught the profession. His father was not at all likely to know anything about distinctions of ships, and was evidently badly informed about this one. It turned out to be a collier, and was bound for Singapore, round the Cape, a voyage which in those days took a very long time. As soon as they got into blue water there was no more cabin life or interesting lessons in navigation. The ship was rather short-handed, and George was sent before the mast as a ship's boy, where he had a very hard time. To have come out of that ordeal unscathed in mind or body, in manners, morals or health, was a marvellous testimony to his real character. It was no wonder that on arriving at Singapore he ran away from the ship, and having somehow come in contact with the United States Consul, was befriended by him, and sent home under better conditions. After a voyage which was not an unpleasant memory, he arrived in England, and eventually turned up at his father's house in Perth, pretty well in rags. This part of his life is not very clearly known to me. He used to talk about it in old days, but I remember more of isolated incidents than of the sequence of events. He was in England for some time from March, 1865, and, according to my diary, he stayed at his old school at Harlow from 20th June to 3rd July. I remember that he took part in the theatricals which were our custom on Saints-day evenings, and there were two (St. John Baptist's and St. Peter's) during his visit. He was a remarkably good actor, absolutely devoid of ' stage fright,' and he kept up his acting well into middle life, and his interest in the theatre down to the end.

From 3rd July, 1865, until the end of 1869, I never saw or heard from him, though I heard of him once. On 24th August, 1866, when my father was consecrated Bishop of Dunedin in Canterbury Cathedral, Tait, then Bishop of London, was one of the assistants. Someone, I think it was Dean Alford, presented me to him afterwards at the Deanery, and I asked after his nephew. He told me that he was still at sea ; but unluckily someone of more importance interrupted before I got any details. I have not been able to find out exactly when he got into the Royal Navy, and if any Navy men read this they must pardon my vague knowledge of the details of the Service in the sixties ; but as far as I can remember there was a way into what I believe was called the master's line from the merchant service at a later age than was possible for entrance into the superior branch of the Service. Those who entered the Navy in this way would become eventually navigating officers, master's mates and masters, as they used to be called, without much prospect of rising any higher. George Fortescue was too old for the ' Britannia,' but apparently young enough for the "master's line." But I am unable to say when he entered the Service. While in that or in the merchant service he made a good many voyages, visited Indian, Chinese, and South American ports, sailed through the Straits of Magellan this last under very unpleasant conditions of weather and was in perils by water not a few. He saw the outside edge of many countries, and had a good many experiences which to the 'gentlemen of England who live at home at ease' would seem strange and wild, but are all in the day's work to a sailor. And all this happened before he was one-and-twenty. At about that age his career in the Navy came to an abrupt end. I am not sure whether it was in manning the yards or in some operation connected with the sails, but he had gone as leader of a party of men on to the cross- jack (pronounced crojjack) yard, which is (or was, as he would have said, when a ship was a ship, and not a box of tools) the lowest yard of the after-mast or mizzen. It seems that in these operations you stand on a rope which is under the yard. He was on it first, and the sudden rush of men behind him caused the rope to sway out from its place, and being a short man he lost his hold of the yard and fell. He was badly knocked about, especially on his head, and had to leave the Service in consequence ; but no permanent injury resulted from it. This is my memory of the tale as it was told to me. My nautical details are probably inaccurate, as they are only a landsman's impressions. The next time that I saw him was in, I think, November, 1869. I was at St. Alban's Church, Holborn, at one of the crowded services held in connexion with a mission which was going on all over London. The service, an evening one, was nearly over, and I was standing near the west end of the church, when George Fortescue walked in, with the half-apologetic expression on his face with which he used to come into school on the frequent occasions when he was late. We spoke to each other for a moment, but he had come there to meet his sister, and had to find her, and I lost him in the crowd. On Good Friday, 1870, I saw him again, at All Saints' Church, Margaret Street, and this time we went out together and had plenty of opportunity for talk. We just picked up the threads that had been dropped in 1865. But I noticed that his old light-hearted recklessness was gone, and that he had more than four years' extra seriousness added on to him. He told me how he had left the sea and was going up shortly for his examination for a Senior Assistantship in the British Museum, for which his uncle, Archbishop Tait, had given him a nomination, and so interested me that, being dissatisfied with my work and prospects as a clerk in the Probate Court, I used my father's influence to get a nomination for myself; and in less than three months from that Good Friday, having duly passed a qualifying examination, I was at work in the Department of Manuscripts. I found Fortescue already on the staff of the Printed Books, though the first time he went up for examination he had failed in spelling ! The Archbishop had been equal to the occasion, and had given him another nomination at once. He went up again, got through, and entered the service a few days before I did. That one of the most efficient men that the British Museum has ever had should only have got in through what ill-natured people might describe as persistent nepotism, may surely be reckoned to the credit of the old system. But Archbishop Tait was a judge of men even of his relations and probably knew of what stuff his nephew was made.

No sooner was George Fortescue appointed than he threw himself into his work with the greatest energy and with something like the enthusiasm which at school he would display for everything except his lessons. He was set to the usual cataloguing of modern books to begin with, and he soon broke through all traditions in the quantity of work which he turned out. Nor was quality lacking, for he had a clear head and an excellent memory. He never wrote a good hand, but that was hereditary, for he used to bring his father's letters round to the MS. Department to be deciphered no easy job. Towards the end of his life his writing became almost as illegible as his father's, but this was due to failing sight and the evil effect of signing thousands of receipts for books under the Copyright Act. In early days, by means of considerable trouble, he kept a hand for cataloguing which was quite good enough for the transcribers. From the beginning he was more interested in work of practical utility and general library management than in accurate scholarship, for, like his ancestors, he was essentially a man of affairs rather than a student, and had little patience with anything that could be described as pedantry, especially if it wasted time. During the interval between my meeting him on Good Friday, 1870, and our joining the Museum staff he in June, and I early in July I saw him often. We took up our school friendship where it had left off, and during that time he confided to me that which I at once saw to be the reason for his changed outlook on life. He was engaged to be married. It was a deep and sincere attachment on both sides, and thus it was that his carelessness of the future, which so long as the future mattered only to himself had been a very marked characteristic, had been replaced by almost excessive care when it concerned someone else also. It was evidently that point in his life's history at which "si trova una rubrica, la quale dice: Incipit vita nova" and it accounted fully for his hard work in the Museum and his hard life out of it.

At first he lived with some other men in a sort of boarding-house in Euston Grove, a short street leading from the Square to the station, a very noisy thoroughfare. Later he moved to the north- west corner house of Euston Square, where he occupied a tiny back room on the ground floor, denying himself every luxury and he was a man who could appreciate luxuries and saving every penny he could. It was not a squalid life, but a horridly uncomfortable one, though he did not seem to mind it. But he never did mind what trouble he took, or what discomfort he went through, if the object was worth it. He went very little into society in those days, and avoided all amusements which cost money, though he was then, as throughout all his life, exceedingly fond of the theatre. His one extravagance, if it may be called so, was his clothes, for he was always well dressed ; but constant care came in useful in that respecft also. All this was probably a hard struggle to a man who was naturally very free-handed. But he attained to great proficiency in the art of going without, and yet it never made him stingy, except to himself.

During the five years between his joining the Museum and his marriage we saw a great deal of each other, almost every day indeed. Commonly we used to meet in the hall of the Museum at four o'clock, and go for a walk of two or three hours, for he was always convinced of the necessity of exercise, and walking was the least expensive form of it. In this way we explored a very large part of London, taking it rather systematically. A good deal of Old London which has since disappeared existed then, and our walks were often very interesting. So to us was our talk which accompanied them. We were neither of us silent men, but we were both of us also good listeners, without which quality conversation may tend to be too one-sided. I have no doubt we talked great nonsense at times, as boys in the early twenties of life will ; but I do not think it was nonsense which one is the worse for having thought and talked at that period of life. Fortescue was then a strongly patriotic British Empire Conservative, at a time when people had hardly yet begun to think imperially. His idea of patriotism was personal service, and nothing which tended that way was too insignificant for consideration. I remember once his refusing to invest a comparatively small sum, which he happened to have, in Russian securities, then rather highly thought of, because it would be helping, however infinitesimally, the credit of Russia, at that time hostile to England. He was a strong Churchman, of the school of Tait, but a good deal because he considered the Church of England a part of the British Constitution ; and he disliked Catholicism, whether Anglican or Roman, the former as to him fantastic and unreal, the latter as anti-national, and both from a certain impatience of what seemed to him niggling and unnecessary details of dogma and ceremonial. In this he developed somewhat differently in later years, and in the end became something of a High Churchman of the moderate sort. His objections were never of the narrow and ignorant Protestant type, for he had come too much into contact with good people of Catholic ideas in both Churches to believe in aledlryotauric tales of Popery. His standard of ethics was always very high perhaps, if such a thing is possible, fantastically so ; but it seemed to be his constant endeavour, in the words of Samuel Johnson which he was fond of quoting, "to clear his mind of cant" and to think with common sense. He was very little interested in any personal application of religion, and hated what schoolboys called 'pi-jaw,' but he was never an agnostic or unbeliever, and took the principal truths of Christianity for granted without question.

On the two fixed holidays of the Museum, Ash Wednesday and Good Friday (for counting legally as a place of amusement (!), it was open on most public holidays, but closed on those two Fast Days), and often on Sundays, we used to go for longer expeditions, exploring the country round London in every direction, and sometimes as a special treat, for it cost money, going up the river in a boat. We could both row fairly well, and enjoyed a not too strenuous expedition of that sort, and in the early seventies the river was seldom overcrowded. Our walking expeditions were often of considerable length, and we got to know the highways and by- ways of the surrounding country, especially to the north of London, very well. One great enjoyment that was open to Fortescue in those days was staying with the Taits, who were always very kind to him, at Addington, then the country house of the Archbishops of Canterbury. There he met all sorts of people of distinction in Church and State, and was taken for the time out of his cramped and commonplace surroundings. It was at one of these visits that there came to him the chance of a lifetime and he rejected it. He was staying at Addington for what would now be called "a week-end," and staying there also was the late Lord Salisbury. Somehow I think because they were the only smokers in the house Fortescue and he were thrown together a good deal. Lord Salisbury was then in Opposition, for it was before the election of 1874, and though he had already been Secretary for India, he was comparatively young, and was not quite the distinguished statesman that he became later. They seem to have talked very freely, and to have got on uncommonly well. A few days later Lord Salisbury wrote to the Archbishop and asked whether his nephew could be induced to come to him as his private secretary, offering quite good terms. It was a great chance of an eventual political or high official career, for either of which Fortescue was well fitted, and he knew that it was; but it must have meant the indefinite postponement of his marriage, perhaps for many years, and he refused the offer. The Archbishop was very irate, but I think that Fortescue himself never regretted his decision.

In those years before his marriage he did a great deal of reading. He was quite conscious of the deficiency which resulted from his educationally wasted boyhood and youth, and made up for it very judiciously. As he seldom forgot anything, for his memory was marvellous, he retained the very fair knowledge of Latin and French which he had acquired by sheer cramming for his examination, and easily added to it. He acquired a good working knowledge of German and Italian, and he had great power of using effectively even a small knowledge of a subject in his Museum work. But as a study he was more interested in modern history than anything else. It was perhaps not so common in those days as it is now to specialise on a comparatively short period and know it thoroughly. But this was what he did rather deliberately, and the period which he chose was the French Revolution, with its sequel the reign of Napoleon. He looked upon the French Revolution as the key to the understanding of all modern politics, probably rightly, and rejoiced greatly that his being given part of the Croker collection of French Revolution tracts to catalogue at the Museum had attracted him to it. He read greedily every book on the subject that he could get hold of, and studied it very systematically. In the end he acquired an intimate knowledge of the Revolution and all its ways and works which has seldom been equalled. But he made curiously little use of this knowledge, 1 though possibly he would have made more had he lived to enjoy the leisure of retirement. He read and he had plenty of time for it in the evenings for amusement as well as instruction, but was rather too hard to please to be a great novel reader. Fairly early he had steeped his mind in Thackeray, knew his novels almost by heart, and could have passed a very searching examination in them. Someone, I forget who, once wrote on "Books that have helped me," or "influenced me." I think that the novels of Thackeray influenced George Fortescue not a little, and that the heroes of them Esmond, the Warrington brothers, Pendennis, Clive Newcome, and the rest, with Colonel Newcome as an unattainable counsel of perfection were his ideals. He might have had worse. It is to be remembered that many of the great early and mid-Victorians were then still living and writing, and their books, and those of many of the lesser lights, were being everywhere read and discussed. Fortescue would generally be found to have read any book that was being talked about, but he usually professed not to be an habitual novel-reader. There were also poets on the earth in those days, and most of us read their poetry as it came out; but I do not remember that Fortescue was specially interested in that form of literature, except that he had a strong dislike for the Swinburne and the Pre-Raphaelite schools. On the whole, in literature he seemed to be an excellent critic, with certain limitations which were largely the result of prejudices. He could not abide anything that savoured of the individualist doctrinaire Liberalism of the seventies, whether in politics, religion, or ethics, and any such taint would set him against a book, however good it might be from a literary point of view.

He could play as well and as strenuously as he could work, whether at outdoor or indoor games. When lawn tennis was invented he took to it eagerly, and got to play very well, for he was aclive in body. He delighted in all manner of card games, and at one time took up chess with a good deal of earnestness. What did not appeal to him in those days was what are commonly called "hobbies" when they were not play and yet had no bearings on the serious work of the world. My Celtic studies he regarded as rather futile, if not pernicious, for he disliked the Celts generally, and especially the Irish, as only a man with Irish blood in his veins can dislike them. That Irish strain, from his maternal grandmother, who was one of the Inchiquin O'Briens, was the one part of his pedigree of which he was ashamed ; and an allusion to his ancestor Brian Boroimhe, the hero of Clontarf, whom he refused to acknowledge as anything but a legendary character, was a sure way of getting a rise out of him. Why should I interest myself in the languages, which were barbarous, of hordes of savages, and in their literature, which was naught ? As for Ralston's folk-lore, he always wondered how a bearded man and Ralston was a very bearded man could waste his time over fairy-tales. There was a good deal of the complete ' Philistine ' about Fortescue in those days. But, like most people, he became more tolerant later in life, and when the study and collection of European butterflies became the absorbing interest of his playtime, so that the habitat of some rare variety greatly influenced his choice of a holiday resort, he began to see that there was something in ' hobbies ' after all.

In April, 1875, the reward of his long years of willing self-denial and hard life came to him in his marriage to Ida, daughter of the Rev. W. Blatch, incumbent of St. John's Episcopal Church at Perth. It was a singularly happy marriage, and the sweet and gentle lady who had been the good influence of his life for those five years continued to be so for twenty-one years of happy married life. They were very poor at first, for they had barely three hundred pounds a year between them, but they did not seem to mind, and were quite light- hearted about it. They lived at first in Maitland Park, Haverstock Hill, where they took part of a house. When I married in 1877 and went to live at Hampstead, we were near neighbours, and saw a good deal of each other at home, as well as in the Museum. Later, I think in about 1883, Mrs. Fortescue having begun to develop the bronchial or lung trouble which eventually ended her life, it was found necessary to go away from that clay soil, and they took a small house on the gravel in Grafton Square, Clapham, where she remained for the rest of her life, and he until he went to live in the British Museum as Keeper in 1899. This house had one great attraction for him in that there was an excellent tennis court in the square garden, though it was rather a dreadful district to live in. Of even this he characteristically made the best, for he attached himself to the Parish Church, where he became a sidesman, taught in the Sunday-school, was on the Committee of the Public Library, and generally interested himself in parish matters, bringing to bear upon these things the same strenuous energy that characterised his Museum work and his play.

It was not long after his marriage that there were some reorganisations of pay at the British Museum, and he obtained his first promotion. Much about the same time there were changes in the personnel of the staff. Rye, the Keeper of the Printed Books, retired, and his place was taken by Bullen, who had been Superintendent of the Reading Room. At the same time Garnett, who had hitherto been occupied in what was known as "placing books" of which presently, was made Superintendent of the Reading Room. For a short time Godfrey Evans, who had been Garnett's understudy in book-placing, took over his work, but he died a year or two later, and Fortescue, who had been his deputy, succeeded him. The work called by the not very exalted name of "placing books"' is a good deal less simple and a good deal more important than its title implies. Also and I can speak from twenty-five years' experience of it it has an interest which belongs to no other work in the department, in that he who performs it sees, even if only for a moment, every book, English or foreign, except those in Oriental languages, which comes into the British Museum. It was during this service that Fortescue acquired a great deal of the knowledge and the aptitude for clear-headed classifying which enabled him to carry out so successfully his later and still more important work. The books in the British Museum are arranged on the shelves by subjects, under a broad system of classification, quite detailed enough for all practical purposes. Indeed, I think the system has hit off a happy mean between under-elaboration and the rather pedantic over- elaboration of some librarians of the American school.

Besides the adtual classification of the books, a great deal of the general management of the library, as far as it appertained to space and arrangement, was in the hands of the "Placer" Fortescue had a very free hand with the placing, for no one except Garnett, who was too busy with the Reading Room to interfere, knew enough about the subjeft to be able to criticise. He introduced many reforms of method, notably the restoration of the system of 'third marks' (adding the number of a book on the shelf to its press-mark and shelf-mark), which Rye had caused to be abandoned, applying it not only to new books, but to those already on the shelves; he also devised a very excellent method of arranging and binding up pamphlets, which added a great deal to his own work. But he did not remain 'Placer' very long.

After about nine years of the Reading Room, Garnett, who had for some time been dividing his attention between his duties as Superintendent and the new work of revising and printing the general catalogue, proposed late in 1884 to devote himself entirely to the latter and to give up the Reading Room. Bond, who was then Principal Librarian, acling on the advice of the retiring Superintendent, and largely, I think, also on that of Mr. (afterwards Sir Robert) Douglas, in whom he had great confidence, offered the post of Superintendent of the Reading Room to Fortescue. He took it, of course, though it did not make any immediate difference to his pay, and was harassing and very hard work, with little to show for it by the end of the day. Garnett, it need hardly be said, was not at all an easy man to follow. He had raised the Reading Room service to great efficiency, and his encyclopaedic knowledge, his marvellous memory, his immense power of work, and his curious tacl: and judgment in dealing with people few men knew better than Garnett when to give special help to readers and when to snub them, and few could do either more effectively made him a predecessor whose standard was difficult to keep up. Fortescue, however, could never be content with leaving things no worse than he found them ; he must go one better, if not more. And he did so in this case. Almost immediately he took over the Reading Room he saw that the great want of the Library was a subject catalogue, and it is with the beginnings of a great reform in this respecl that his memory will always be associated. The printed accessions to the general catalogue, which had been issued since 1880, made the task of constructing a subject catalogue for the accessions for 1880 to 1885 possible, and it was naturally these recent books which were most in request. He began his index by way of making his own work more effective, doing it in his own time, chiefly at home, but eventually suggested to Bond that it should be printed officially. Now, there are two forms of subject catalogue a subject index, and a class catalogue. Fortescue, after much thought, decided that whereas anyone who knows the alphabet can use a subject index, a class catalogue, owing to the numerous differences of opinion on the classification of all knowledge, is of much less service, unless you have the man who made it standing by to show you how to work it. Otherwise, it is often more business to find out what should be read than to read it when it is found out. Bond, who had been Keeper of the Manuscripts, had signalised his Keepership by organising the construction of a really very useful Class Catalogue of all the Manuscripts, and was prejudiced in favour of this form. Thus it was that, though he took every interest in Fortescue's work, his well-meant interference, always in favour of large subject headings, gave a good deal of trouble in the making of the first quinquennial volume, which was certainly not so good as its successors, though it was a splendidly useful book all the same. In the later volumes Fortescue had a completely free hand, and the results of that, and of his own improved knowledge of how to do it, were very apparent. After three volumes had appeared, containing the accessions of five years in each, and a new volume was due, the preceding volumes were thrown into one alphabet with the accessions for the last five years, and a twenty-years catalogue in three volumes was published. Since then two quinquennial volumes have appeared, and we have now, as the greatest memorial of Fortescue's work, subject indexes of the great bulk of the literature of thirty years. Certain branches, such as novels, sermons (unless on some very definite subject), biographies (which are provided for by biographical crossreferences in the general catalogue), poetry, plays, and a few others, are regarded as outside its scope ; and so are such works as Bibles, liturgies, etc., for which the general catalogue provides headings already. The idea is that of a subject-supplement to the general catalogue, and no useful purpose would have been served by repeating information which the general catalogue already provided. Though in the three volume index and the two successive volumes Fortescue, being then Keeper, delegated a certain amount of the work to others, he kept for himself so complete a supervision that his own mind is perceptible through them all.

He found the work of the Reading Room very anxious and worrying. He got on extremely well with the readers, and made many real friends among them ; but the mere management of so large a number of people in one room must always be a hard task, and among the thousands who hold reading tickets there must always be a few who are cantankerous, self-assertive, and unreasonable, as well as a few a very few of a blacker sort of sheep. Very possibly he concerned himself needlessly, for in actual fact during his twelve years tenure of office things went extremely smoothly, and in the very few cases of trouble he was so evidently right that he rather strengthened his position by them than otherwise. Over and over again, however, when we went out to lunch together, I found him worn, wearied, and harassed, and inclined to use nautical words about the whole business. The Reading Room got on his nerves, and he suffered a good deal from insomnia at that time. Partly because the Reading Room took so much out of him, and partly so that he might devote his evenings to the side issues of the work, such as his index, he gave up most amusements except, during the summer months, a little tennis of an afternoon. He had been very fond of amateur theatricals. He was a very good actor, and in the early eighties there was a little informal dramatic society, which originated at the house of R. H. Major, the former Keeper of the Maps, and consisted chiefly of Fortescue, Mrs. Godfrey Evans and her sister, Miss Major, and myself, with occasionally others, when more than four characters were required. We used to go about acting in parish-rooms and school-rooms for charitable purposes, and it was a great delight to Fortescue to get up these entertainments. But he was obliged to give up everything of this sort when he took over the Reading Room. The strain was too great.

In one respect he was rather hardly used. Bond had promised him, rather vaguely and informally, no doubt, the next Assistant-Keepership, for he was doing the work of it without the pay. When a vacancy did occur, Bond did not give it to him, though he was not really passed over, for the new Assistant-Keeper was his senior. I think, indeed, he was somewhat of an "accessory before the fact" to the appointment, for he always forbore his own advantage. However it came about, he had been doing the work of an Assistant-Keeper for six years before he was actually receiving the pay. In 1896, after twelve years as Superintendent, Fortescue, being then the senior Assistant-Keeper, retired from the Reading Room to take his part, under Garnett as Keeper, in the general work of the department.

Then came upon him a terrible and unexpected sorrow, which overshadowed all the rest of his life. Mrs. Fortescue, who had been something of an invalid for some years, died after only a few days of really serious illness, and he never really recovered in health or spirits from the blow. For four years he lived on at Grafton Square in solitude, looked after by a faithful servant, who had been with him for a long time. In 1899 Garnett retired, and Fortescue became Keeper of the Printed Books. In consequence of this appointment he had to remove to the official residence in the British Museum. In the autumn of the same year he married again, and his second wife (Beatrice, widow of Dr. H. Webster Jones) has survived him. His reign as Keeper was a fairly long one. The work of the head of so large a department, equal to or even greater than all the rest of the Museum put together, is necessarily of a very varied character, and consists quite as much in the management of men as of books. And a great deal of it does not loom large before the world, or remain much on record after the worker has passed away. Unless some important event connected with the department happens to occur, there is little to distinguish one keepership from another, except perhaps some intangible improvement or deterioration in the standard of work and the morale of the department generally. But there was one quality which distinguished Fortescue's regime from all that had preceded it. There had been good Keepers before Fortescue, and there had been popular Keepers, but in my experience of the British Museum, which is a long one, and also in the traditions of the elders, never did I meet with a case in which the head of a department gained so completely the affectionate devotion of those under him. In olden times it had been rather the tradition for Keepers to be, if one may say so, a little 'stand-offish ' or patronising to those under them, and especially with junior men. They might talk and even joke with them in a superior sort of way, but discipline had to be maintained. I do not think the Keepers liked it, any more than the captain of a man-of-war necessarily enjoys his solitary grandeur. But it somehow came to be so. Fortescue, not of any set purpose for I do not suppose that he ever thought about it but simply by being himself, put an end to the last remains of the old tradition. He treated all alike, and no one presumed upon it, while all responded. "Popularity" is not the word for the feeling he evoked; it was affection.

The result of this personal feeling towards the Keeper acted exceedingly well on the work. His practice was to let every man as much as possible do his work in his own way, and to interfere as little as possible with details, and never for the sake of asserting himself. This had not always been the tradition, though in fairness I must say that during the twenty-five years of my work as placer of books under three Keepers, I was never interfered with by any of them, which in the case of Garnett and Fortescue was not for want of knowing the work. It answered well when applied to the whole department. The most prominent event of Fortescue's Keepership was the temporary closing of the Reading Room and the reorganisation of its contents in 1907. It was a big thing. Sixty thousand volumes were taken out of the Reading Room, and arranged elsewhere (a difficult problem), so that they could be got at if required. This reference library was completely revolutionised, and what was really a new selection put back, for all the obsolete books were weeded out and others substituted to bring the collection up to date, while the whole was so rearranged that hardly a book, on the ground floor at any rate, remained in its old place. All this had to be done in six months, with business carried on as usual during the alterations while the Reading Room was being redecorated and repaired after the first fifty years of its existence. This was followed by a new and highly improved catalogue constructed under Fortescue's direction. Besides this catalogue and the five volumes containing the Subject Index for thirty years, all of which were issued during his Keepership, under his direction and very largely as the work of his own hands, he also edited, and to a very great extent constructed, an important catalogue of the great collection of pamphlets, books, newspapers, etc., relating to the Great Rebellion, originally brought together by George Thomason, a bookseller of the time of King Charles I. During his Keepership there appeared also the first two volumes of the catalogue of the fifteenth century books in the British Museum, which had been brought together into one place and arranged according to place and printer (except for a small proportion left undone at the time of his death) by the late Robert Proctor.

Of the doings of the department and its Keeper after May, 1909, I cannot speak much from personal knowledge, for I retired at that time and went to live in the westernmost part of my native Cornwall. But during my rare visits to London I always saw him, and we kept up something of a correspondence by letter. ( During 1909 and 1910 he was President of the Bibliographical Society, having already held the same position, in 1901, in the Library Association, in both cases with conspicuous success. Another office which came to him as Keeper of the Printed Books was that of a trustee of the Carlyle House at Chelsea, and in this, though he was no great admirer of Carlyle, he became warmly interested.) During those years his health was often very bad. Indeed, he had very much illness during nearly all his time as Keeper. At the beginning of it he had been suffering from a distressing malady, of which an operation, serious though not dangerous, completely cured him, though he took a very long time to recover. Then he found his sight seriously affected, partly by diabetes, which he had developed, and still more by excessive smoking. He was a ravenous cigarette smoker, and it was a terrible affliction to have to give it up. But blindness, which he was only just in time to avoid, would have been the penalty of continuing. The diabetic trouble continued, and the disease was only kept at bay by very strict diet, always a very irksome thing to him. In December, 1909, he was suddenly seized with acute appendicitis, and operated upon immediately. For weeks he hovered between life and death in the nursing home to which he had been taken for the operation, and then in his own house. His recovery was slow, and for many weeks anything but sure ; but eventually, owing in a great measure to the unremitting care and devotion of his wife, he recovered sufficiently to go abroad. There he remained for some months, and did not return to work for eight or nine months after the first seizure. Though very much weakened, he continued fairly well to all appearances, though the diabetes returned and troubled him a good deal. In October of 1912 came the end. Under the rules of the Service it was necessary that, having arrived at sixty-five, he should retire, and his old colleagues had decided to give a combined farewell dinner to him and to Mr. H. A. Grueber, the Keeper of Coins and Medals, who retired at about the same time, on 29th Oclober, the day before the date fixed for his retirement. In the middle of September I was in town, and saw him several times. One day he took my wife and myself over the new buildings which reminded him and me of the adventures in those other new buildings in 1863, of which I have already spoken. On another day I had tea with him at his club, and on the morning of 28th September I saw him for the last time in his room at the Museum. He seemed perfectly well, and said that he was better than he had been for years, but was dreading his retirement terribly. He had invested his whole mental capital in his Museum work, and losing it he was bankrupt, for he had no other resources. Nothing could take its place. When we parted he said, perhaps not quite seriously, that he should like to go to that dinner, but he wished he could die the next day. Wishes are not often so nearly granted. It was on the day after the dinner would have taken place that he was buried. About a fortnight after our last meeting he was taken with a complication of results of the chronic malady, and got worse and worse, until on the morning of 26th October all hope of recovery was given up, and he passed away at midday.

His work was done, and he died, as he had always wished, in harness. His was not an eventful life, though a very active one, and perhaps his memory will not endure very long, for he has left little in the way of literary work, and the only recognition which he received was an honorary LL.D. from the University of Aberdeen. But to those who saw and appreciated his lovable personality, his loyalty, his generosity and his selfabnegation, he will be a fair memory while life shall last.

Requiem aeternam donet ei Dominus et lux perpetua luceat ei.

HENRY JENNER.

Ref: file:///C:/Users/Edward/Documents/Full%20text%20of%20The%20Library%20(re%20Fortescue%20family).htm

Research Notes: Research Notes:

Image Courtesy Messrs. Elliott & Fry, Ltd., and the Open Library.org

Other Records Other Records

1. Census: England, 30 Mar 1851, Alveston WAR. George is recorded as a grandson aged 3 born Alveston WAR

2. Census: England, 8 Apr 1861, Charterhouse School Charterhouse MDX. George is recorded as a pupil a foundation scholar aged 13 born born Aston Cantlow WAR

George married Ida BLATCH [14691] [MRIN: 5213] on 22 Apr 1875. (Ida BLATCH [14691] was born about 1839 in Chelsea London.)

George next married Beatrice ST LEON [14692] [MRIN: 5214], daughter of Dr H WEBSTER-JONES [19339] and Unknown, on 9 Oct 1899 in Reading Berkshire. (Beatrice ST LEON [14692] was born in 1854 in Cadiz Spain.)

|

General Notes:

General Notes: